Review by Will Preston

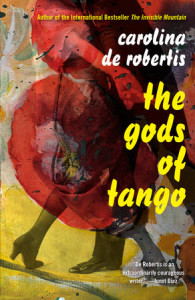

The Gods of Tango

by Carolina de Robertis

Penguin Random House

Available May 17, 2016

It’s 1913, and Buenos Aires is a picture of bedlam. Exploding with an influx of immigrants, the city is a clattering, volatile place, filled with “thousands of jostling voices and hands itching for work,” (81) its streets perpetually on the brink of violence. It’s the type of city where a musician, playing in a crowded nightclub, can be stabbed to death by a drunken rival, only for the crowd to shout impatiently for more music; a city where another man can climb onstage, pick up the violin—still “sticky with blood, a raw-copper smell [rising] from its bridge” (121)—and resume playing.

It’s 1913, and Buenos Aires is a picture of bedlam. Exploding with an influx of immigrants, the city is a clattering, volatile place, filled with “thousands of jostling voices and hands itching for work,” (81) its streets perpetually on the brink of violence. It’s the type of city where a musician, playing in a crowded nightclub, can be stabbed to death by a drunken rival, only for the crowd to shout impatiently for more music; a city where another man can climb onstage, pick up the violin—still “sticky with blood, a raw-copper smell [rising] from its bridge” (121)—and resume playing.

Into the middle of all this steps Leda di Mazzioni, seventeen years old and fresh from the Italian countryside. Leda arrives in Argentina with only a few folded dresses and her father’s violin, burdened with guilt over the suicide of her cousin Cora. She hopes to start anew in América with her new husband, Cora’s brother Dante. Expecting to meet him at the dock, however, she’s greeted instead with news of his murder, shot to death by police during a protest by striking workers.

Alone and destitute, a shell shocked Leda locks herself away in Dante’s conventillo. She seeks solace at night by dressing herself in her dead fiancée’s clothes, sliding into his trousers, his vest, his shirt. She’s shocked by how naturally they fit to her thin, boyish frame, and mortified by the rush she feels, the sense of freedom. “What kind of woman does this thing?” she scolds herself. “She was not a man. She was a woman. Wasn’t she?” (103)

All the while, seeping out from courtyards and through open windows, she hears the strange strains of the tango: vigorous, desperate, its melodies “rich as night.” (93) Leda, entranced, spends her nights in Dante’s clothes and silently playing her father’s violin, her arm “miming the motions of an invisible bow.” (96) Faced with a future as a seamstress or a prostitute—the two occupations available to women—Leda arrives at a different, dangerous decision. She binds her chest. She assumes Dante’s name. And she steps out into the hot, murderous city as a man, to make a living playing the tango.

It’s at this point that The Gods of Tango, the third novel from Uruguayan-American author Carolina de Robertis, truly comes alive. Although the tango provides the backbone for this rich story, de Robertis is ultimately more interested in the process of rebirth, of how to define yourself in a city where your role is decided for you. Every character in this broad and occasionally spellbinding book has been rebaptized by Buenos Aires, often literally: from the motherly prostitute christened Mamita by her clients because “Mamita is what they want of you whether they know it or not: they are all boys inside desperate for their mothers’ skirts” (230); to Santiago, a charismatic bandoneonist inescapably nicknamed “El Negro” for the dark olive tone of his skin. Even the tango is changed irrevocably, swelling in spite of itself to include the piano, the double-bass, the voice. “A man does not name himself in a city like this,” de Robertis writes. “The city names the man.” (186)

And so Leda’s gradual transformation into Dante—both physically and, eventually, mentally— probes intriguingly at this question of identity. How much of yourself can you lose and still be yourself? And how much of what you lost was really you in the first place?

The trope of reinvention is one common to the American mythos, but de Robertis has not only shifted it south, but applied it here to issues of gender and sexuality. Soon after her transition into Dante, Leda is scandalized by the fascination she feels towards the prostitutes working in the dim nightclubs and brothels, her desire to see their bodies. “She’d never heard of such a thing. It had to be impossible or else demonic, the worst kind of sin, beyond hope of penance.” (169) But, in one of the novel’s most beautifully realized passages, she finds herself alone in a room with one of them, a little “sparrow-girl,” overwhelmed by the girl’s fragile beauty: “The sight stirred something in Dante that was fierce enough to break her. This brutal city was full of noise and blades and death and dirt and hunger and also this, a naked girl so beautiful she put the stars to shame.” (169) It is her reincarnation as Dante—her determination not to let the city name her—that allows Leda to even consider this part of herself, an arc that leads into a sequence of torrid affairs and slow self-acceptance.

De Robertis’ rendering of Dante-who-is-also-Leda works best when at its subtlest. The author speaks volumes with a single pronoun. Although the pronoun “she” is utilized for most of the novel—as Leda, despite her burgeoning sexuality and outward dress, still self-identifies as female—the middle follows a curious progression. “He” is at first only utilized to signify other characters’ perceptions of Dante, before making sly entrances to signal his own progression towards identifying as male. By the end, de Robertis writes, “the gap between inside and outside, self and disguise, truth and pretense, had narrowed and thinned until it became invisible to the human eye.” (357) We close in a thoroughly masculine perspective.

But the novel would have been stronger had de Robertis employed such a light touch elsewhere. Dante’s sexual awakening culminates in a forbidden love-triangle whose importance feels misjudged; the stakes, previously built around Dante’s very survival in a city that wouldn’t hesitate to tear her limb to limb, are retied to one of its least compelling plotlines. It doesn’t help that de Robertis’ language often veers into melodrama, and many of her images feel so underlined that any sense of subtlety is lost. One woman, trapped in a loveless marriage to an older man, becomes obsessed with buying and releasing caged birds, “straining to memorize the exact slant of their wings as they soared off so she could call it back in times of despair.” (265) Another character, an emigrant watching Argentina draw closer from the bow of a steamship, imagines that the awning on the dock should be “emblazoned with the words LAST HOPE, because that was what this place was to so many of the people on this ship.” (44) A crucial unmasking late in the novel occurs, inevitably, at a masquerade. With such a topical, richly thematic story, one wishes the author had trusted her writing to speak for itself.

For when she does, the novel feels fresh and inventive. De Robertis tells Dante’s story episodically, weaving a wide tapestry of Buenos Aires as people flit in and out of Dante’s life. They are all immigrants, each forced into a new skin: Neapolitans, Uruguayans, Poles. [“Isn’t that strange,” Leda wonders upon first arriving, “the way one city can swirl inside another.” (99)] And in each chapter, the author slips out of Dante’s point of view and drops into theirs: beleaguered prostitutes, blind violinists, a young anarchist inadvertently responsible for the death of his best friend. These short segments, rarely more than four or five pages, demonstrate de Robertis’ talent for conjuring characters with only a few strokes; their voices and stories are vividly alive, at times so much so that returning to our furtive protagonist can be a disappointment. For it is in these moments, as much as Dante’s slow metamorphosis, that the novel’s questions of identity truly flourish: a vast congregation of people, far from home, all attempting to reconcile what it means “to disappear from your own life; to reappear into another one.” (126)

A native of Williamsburg, VA, Will Preston has since lived in Oregon, England, and the Netherlands. He has written extensively on travel, music, and history, and was most recently published in Rowan University’s Glassworks Magazine. He is currently an MFA candidate at the University of British Columbia.