Interview by Matthew Walsh.

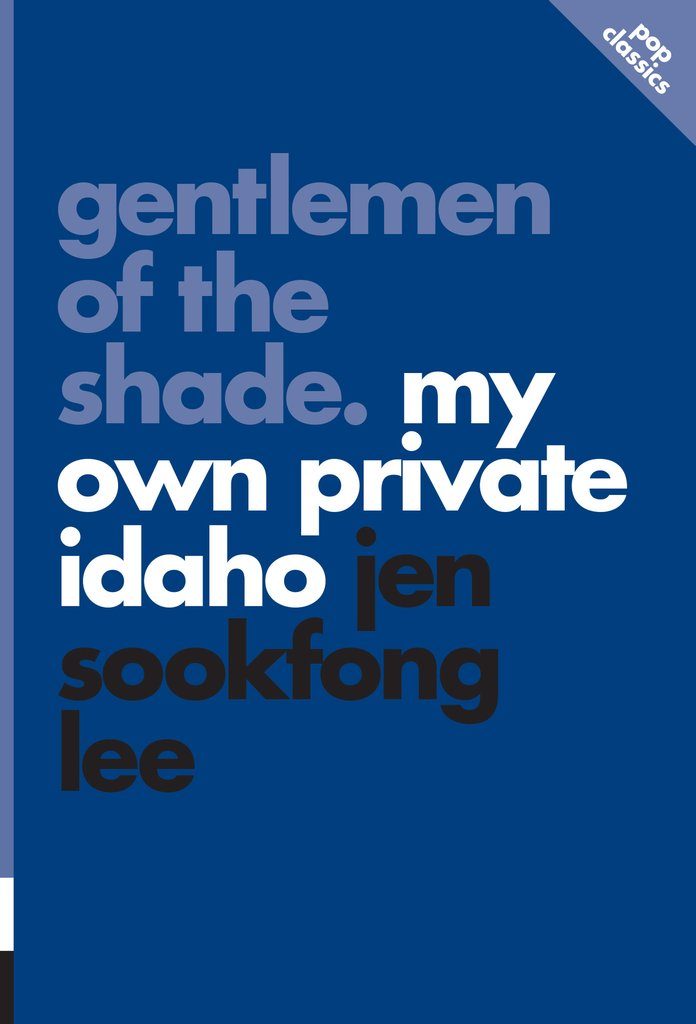

Jen Sookfong Lee’s new book, Gentlemen of the Shade: My Own Private Idaho, is part film analysis and part cultural commentary, with glimpses of memoir. The book focuses primarily on My Own Private Idaho, Gus Van Sant’s 1991 film about two drifters—but there are asides that delve into 90s pop culture in general, with mentions of Kurt Cobain and Nirvana’s Nevermind album. My 90s memories returned to me through my reading of this short, precise analysis of 90s art and culture—a period when “our connection to beauty [was] universal, as [was] our search for identity.”

The book is a deep character analysis of the two main characters in the movie, Scott and Mike, but there are also moments of memoir interspersed with the talk of cinema. Working on this project, did you discover things about the movie you hadn’t noticed before, or remember anything from the 90s that you had forgotten?

Yes, so much! I hadn’t thought of [the R&B group] Color Me Badd, for example, for twenty-five years. I know My Own Private Idaho so well and had watched it so consistently over the course my life that I don’t think there was anything I discovered when I was writing the book that I hadn’t noticed before. But what the book did force me to do was consider the choices Gus Van Sant was making. Why did he cast Hollywood teen idols? Why were the johns in the film so eccentric? All of that.

The film is an original in a lot of ways, to me at least. The 90s is the decade I grew up in too, but I never saw this movie until I was much older because of the content. What was it about the film My Own Private Idaho that made you want to write a book about it, and are there any other films you continue to return to?

My Own Private Idaho felt like the first cultural subversion I experienced and understood. I had been tentatively exploring the idea of the alternative, or of making choices based on a set of factors entirely separate from what my parents might consider. I saw the film when I was fifteen, which is a pivotal time for independent thinking, and it truly felt like a switch went off in my brain. All of a sudden, I wanted to subvert culture too! There are films that I have gone back to, but very few hold up. Dead Poets Society, for example, which I loved at fourteen, seems stalkery in 2017. If there was one other movie I could write about, it would be Singin’ In The Rain. I know. But Debbie Reynolds and Donald O’Connor!

On page seventy-four you write, “what we had learned from Mike and Scott […] was a pivotal part of what we needed to feel creative, and essentially human: building a centre when we were the other, searching for purpose when purpose didn’t come to us,” and I’m curious about how that feels now for creators and artists—whether it’s writers or filmmakers. Could you talk a bit about that?

I don’t know that this process of centering your creative self and idiosyncratic voice ever really changes. In order for us to believe that what we create is worth dissemination, we have to make our own spaces for our own narratives. I do believe that My Own Private Idaho made it seem that this centering was possible. If Mike and Scott, the queer street hustlers, were worth an entire feature film, then maybe my stories of being a Chinese Canadian girl in East Vancouver were worth something too. Artists are constantly chipping away at the mainstream; after all, we’re always looking for the narrative that hasn’t been told yet; otherwise, why bother? Centering your voice and believing its value is the trick we play on our brains to make creativity possible.

You write that Van Sant’s filmography can seem random, but makes a chaotic kind of sense, yet all the films deal with similar themes. I know you yourself have also done a myriad of things in your career. Novels, poetry, criticism, essays, and also broadcasting with Can’t Lit. Do you see similar themes popping up in your own works, despite the forms being very different?

For sure. I think I’m always interested in the intersections between communities. It can be easy to write stories about a cast of characters who all live in the same place and have the same kind of jobs, interests, and relationships. This bores me so totally! I like those points where seemingly disparate people come together and what happens in those moments. I also made a commitment to myself a long time ago that I would write the invisible stories. I think about the people who don’t have public lives, who, when they die, will take their stories with them. And I try to write those stories, whether that’s in poetry or prose. And it extends to Can’t Lit and anything I do with CBC. What authors and books are essential to the literary landscape but need a little push for people to find them?

As a writer, you’ve tackled many genres and styles—is there one, like writing a film script, that are you are interested in trying?

I have no desire to ever write a screenplay! You can print that and I will stick to it! I’ve been toying with the idea of co-writing a series of poems with a couple of my poet friends. Also, I kind of want to write a porn novel. Like, a good one. Although maybe all porn authors say that.

I know that it’s touched on in the book, but why do you feel that My Own Private Idaho has such a lasting appeal to audiences?

Ultimately, My Own Private Idaho is classic storytelling, with Mike and Scott’s coming-of-age and their love story. And the world will always want those narratives. But I also think Gus Van Sant has, possibly accidentally, created a timeless aesthetic that speaks to people younger than me. You could place Mike and Scott in a contemporary film and they wouldn’t look out of place. But also we see so much of the 21st century in this film, or at least the beginnings of ideas or movements that are now part of our daily conversations. Topics like gender fluidity, sex work, and queerness.

If you had to pick a favourite sequence in the film as one that speaks to you the most—for whatever reason—which one would stand out to you?

Oh, easily it’s when Mike is on a date and is scrubbing the house dressed as a little Dutch boy. I giggle madly every single time.

You mentioned before that you work as a freelance writer, and you also write novels, and even have some amazing poetry in The New Quarterly. I’m curious about what you might be working on now—could you share a little bit of your next project?

Right now, I’m trying to finish a poetry collection. I’ve been chipping away at this book for two years now and I think it’s almost time to release it from my death grip. I’m also co-editing an anthology of essays about sexual assault with Stacey May Fowles, which has been an emotional experience so far, but a good one. I am also percolating a novel idea, which I hope to start in January. SO MANY BOOKS.

Matthew Walsh is a poet and short story writer whose work appears in Joyland, The Malahat Review, Arc, Bad Nudes and others. twitter: @croonjuice