Photo by Alexa Jane Battler

Interview by Natasha Ramoutar

Adrian De Leon seems to have come out of nowhere. With only a handful of literary journal publications to his name and no blurbs on the back of his book Rouge, he has managed to land features on outlets like CBC’s Metro Morning and Open Book and earn invites to esteemed reading series like Pivot and Speakeasy.

But he did come out of somewhere: Scarborough. For those who know him, his fast ascent and the warm reception of his debut poetry collection Rouge weren’t surprising at all. De Leon had been working on Rouge since 2013 with Daniel Tysdal, a poet and creative writing professor, and has been active in the Scarborough community just as long.

With all but two poems named after subway stations, the collection at first glance looks like it’s about the TTC—Toronto’s public transit system—but Rouge was actually written in response to the Danzig shooting. The Danzig shooting occurred on July 16, 2012 at a block party on Danzig Street in Scarborough. Three men shot at a crowd of two hundred people, resulting in two deaths and twenty-four injuries. The response from city officials was equally as concerning, with generalizing statements about that racialized community and insisting that they needed to be “put to work.” Situated at the east end of Toronto, the suburb of Scarborough was and continues to be misrepresented as crime-ridden, and these types of statements further villainized the community.

For De Leon, who is completing his PhD in History at the University of Toronto after a BA in English, there is a synergy between his academic work and creative writing, which focusses on both gentrification and tokenistic diversity, and prioritizes marginalized communities. Rouge isn’t just a collection of poems—it’s an acknowledgement, it’s a love letter, it’s community work.

Within Rouge, the idea that the city is the poem becomes complicated as we think about who has access to move through the city and how we conceptualize Toronto. Bring your Presto card, prepare for delays, and come through on this journey with Adrian De Leon—we’re ridin’ through the 6 with our woes.

Spadina

A Chinatown Demographic Distribution

We could hear the desolate country / is disjointed DIN / shop shop! -shop/in bouncing Oriental tongue / in my mind nostrils / tender warm pork / span sweetness stamp

(Excerpt: Adrian De Leon, “Spadina”)

Adrian de Leon [ADL]: There are some poems that feel like you can glide over them because I make them banal and I make them kind of copy and paste. That copy and paste form is something I specifically thank Sachiko Murakami for in her Vancouver special poems. Replication, gentrification, homogenization, modularization—there is no Rouge without [Sachiko Murakami’s collection] Rebuild. As much as it came after [Carrianne Leung’s] That Time I Loved You, [David Chariandy’s] Brother and [Catherine Hernandez’s] Scarborough, its direct lineage is Vancouver literature.

Natasha Ramoutar [NR]: When you’re talking about Rebuild, are you talking about the written collection, the online component or both working together?

ADL: There is no distinction for me. Spadina was one of the earliest poems I wrote explicitly because of Rebuild. The first time I heard Sachiko Murakami speak, she talked about how she lost the original poem. I didn’t lose the original poem in this case, but I wanted to see how Google Translate could help me degenerate the original. I wanted to play in that specific neighbourhood. I translated from English to Google’s version of Mandarin then back to English. Then I took that and [put it into] Google’s version of Cantonese then back to English, then Google’s version of Vietnamese. It just keeps degenerating. It was ready-made.

Jane, (Leaves Of)

To the “earlier delay,

I am with you.

To callooh, callay,

I am with you.

To the stroller-bound angels on wheels,

I am with you

To the dust creeping at my heels,

I am with you.

(Excerpt: Adrian de Leon, “Jane, (Leaves Of)”)

Adrian De Leon [ADL]: In writing about infrastructure, I’m also trying to write beyond Walt Whitman. Walt Whitman, par excellence, is the white male American commuter poet—“Crossing Brooklyn Ferry,” Leaves of Grass, thinking about living in New York. I look at poems like Chen Chen’s [“In the City”], and about the ricketiness of holding dumplings being with friends or like Oubah Osman[‘s “Delay Both Ways”]. So Jane is about that. I don’t really subscribe to this whole bullshit, you know, of Jane and Finch as dangerous, right? I love that neighbourhood, number one. But number two, there was a train delay and I thought okay, this is it. I guess that was my experience just waiting. It was nice and mundane, cause that’s what I got from Jane.

Commuting creates intimacy. I think infrastructure, cars, being economic subjects, working, making money, that promotes us to be individuals on our own and force the world to be at our drumbeat. Commuting is forced synchrony with strangers. As much as I trashed Whitman, I think that’s precisely why his stuff gets me. That’s what commuting is, that’s the ethical encounter that commuting forces us to do and confront. To look at people or not look at people, to think about being close to other people that we don’t know, that we didn’t choose, but are also as human as us right now.

Lawrence East

from the ochre-concrete face south of the bridge

four pillars around my newfound nest,

i felt like a king.

(Excerpt: Adrian de Leon, “Lawrence East”)

ADL: I wanted to talk about that building, the second place I ever lived in Canada. I remember getting picked up by some family friends and staying in their basement, and I remember sitting sleepless on the stairs. Then we moved to this place, also with family friends, so we just kept getting passed around. I think part of the reason why my parents wanted to get a house was that it was a way of paying it forward. So whenever someone would need a place to stay, they had somewhere fixed for several years. We were bounced around a lot.

These buildings are meant to be overlooked. They’re utilitarian. I’ll be audacious and say I want this book taught in classes. You’re forced as a reader to look at these places that are deliberately designed not to be looked at. It’s like you’re looking at this boring-ass building. This is where the magic happens.

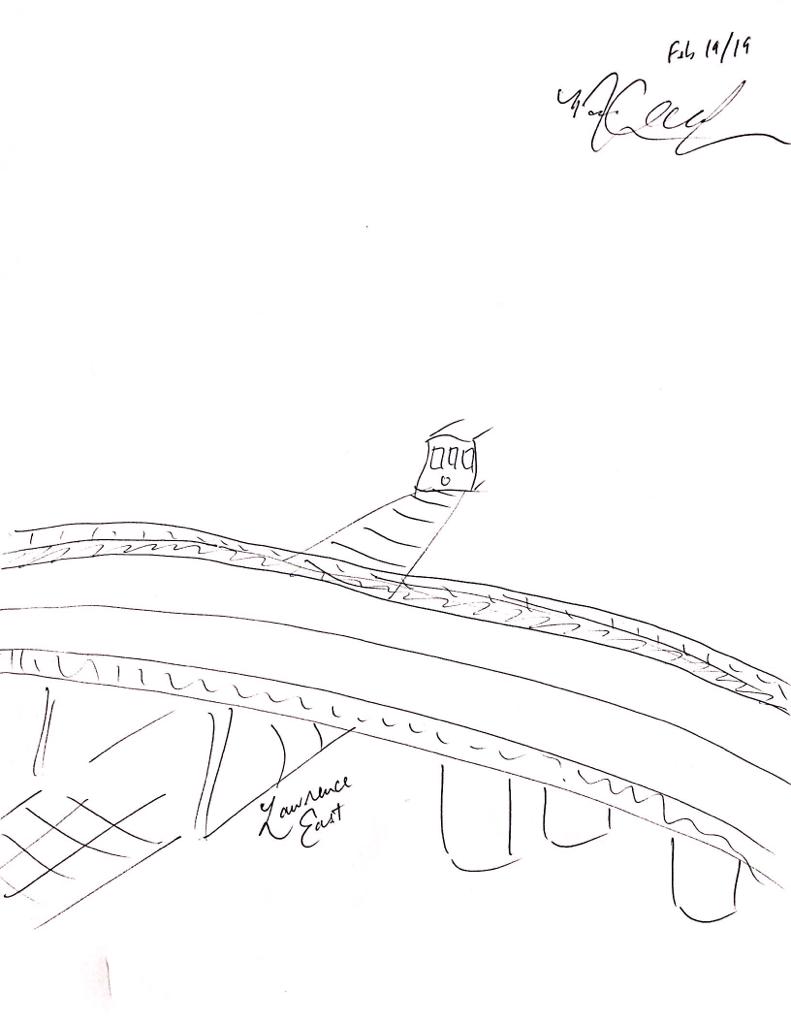

Lawrence East Station, as sketched by Adrian De Leon.

Leslie

On Sundays, Daddy used to drive us down

To let IKEA start our day. A tank

Of gas would cost us more than eggs and meat.

Potatoes, too! Those golden wedges meant

To make us feel deliciously at home,

But neither Mom nor Dad would dare to cook

Potatoes without beef and lard from cans

Or big ol’ helpings from the tube

Of Tex-Mex (or whatever else the South

Could grind and clobber in memoriam

Of Alamo.) Hmm. Maybe home is one

Of those weird Swedish names they stick on chairs

And light bulbs, cushions, blankets, even meals.

To stretch that tank of gas, we’d spend a whole

Day after Catholic Mass to stuff our plates

And faces with those “home fries,” eggs, and bacon.

I think that home was in those fries. We stayed

So long at times that even janitors

Would get to know our names and stuffed faces.

The chairs, the beds, the showrooms: our playground.

The setting sun, it darkened Scarborough first—

IKEA candles, rays of light, burned brightly.

(Adrian De Leon, “Leslie”)

ADL: The one that gets my dad and mom is Osgoode, and that’s because it was about when my dad became unemployed. But the one that gets my brother is Leslie. He immediately flips to Leslie and he reads it and starts laughing. He’s like, “You know, I was waiting until I got to Leslie and I wondered if you had the same memory as me.”

When we were dirt broke, as a special occasion after church, our parents would drive us to IKEA [near Leslie station] to get the dollar plates of meatballs because they were cheap and they were delicious. I remember accidentally seeing a slip of my parents’ bank account. I was really young and I saw thirty bucks. It was through those years that they would take us to IKEA a lot to stretch things out. They’re doing okay now. My dad’s back to work, he’s working his dream job as a pastor and psychotherapist at Scarborough Hospital.

But during that time it was hard, it was fucked. It was really nice to see that even my brother who is 18 can look back and be like, “Oh yeah, I noticed that too. I didn’t say anything because I got it.”

Leslie means a lot to me.

On Rouge I and II

[Poems omitted at author’s request]

NR: Will you read the two Rouge poems?

ADL: I won’t. Even though I knew it was mine to write, it was never mine to read. I wasn’t at the block party. I wanted to piece and put it together. I keep forgetting which Dionne Brand poem inspired Rouge, but it’s the one where she takes, I think, these historical, colonial and slavery cases and then deconstructs them and puts them back together. They’re very difficult to read. Not just like affectively but formally. As are these. When I read them out loud they’re difficult to read. They’re traumatic. Even if it’s “my book,” this book will never feel easy for me. Because it’s a work that never feels done.

I’m gonna say a word that I love that comes out of critical theory: constellations. If we’re all stars, the entire point is to find these ways to connect and tell stories of connecting. Jane (Leaves Of) was like I’m gonna hear someone pushing a stroller, I’m with you, that’s a constellation. I am telling a story about that one random connection in unexpected ways. These stories can be arbitrary, but they can also be signifying. I think that’s why I keep coming back to these two last poems.

The first Rouge is so hard to read because they’re not my words. They’re the tweets and the interviews and the reports and the song that came out of that moment. Therefore, it’s not mine to read out loud. I’d rather different people read it at different iterations in different parts of it than me.

Adrian De Leon refuses to claim that he was inspired by the Danzig shooting because he feels as though the word inspired is often framed to be positive. Instead he states that he’s inspired by his community and his relationships. That political moment of the Danzig shooting in 2012, “wasn’t inspiration, it was a call.”

As the interview nears its end, he remembers wanting Rouge to be published and become obsolete. While he hoped Toronto would be in a better place politically and in terms of infrastructure, the book is now more relevant than ever. He notes, “We have a Ford in office again, we have Tory extensively continuing the racial capitalist regimes of Rob Ford. Just like Trudeau and the pipelines and settler-colonial capitalism.”

Rouge is relevant in the way we’re dealing with transit again, the way that we’re dealing with the state of vulnerable communities nationwide. As De Leon notes, “It’s still alive. That trauma is still alive.”

“Speaking of transit poems,” he asks, “where do we go now?”

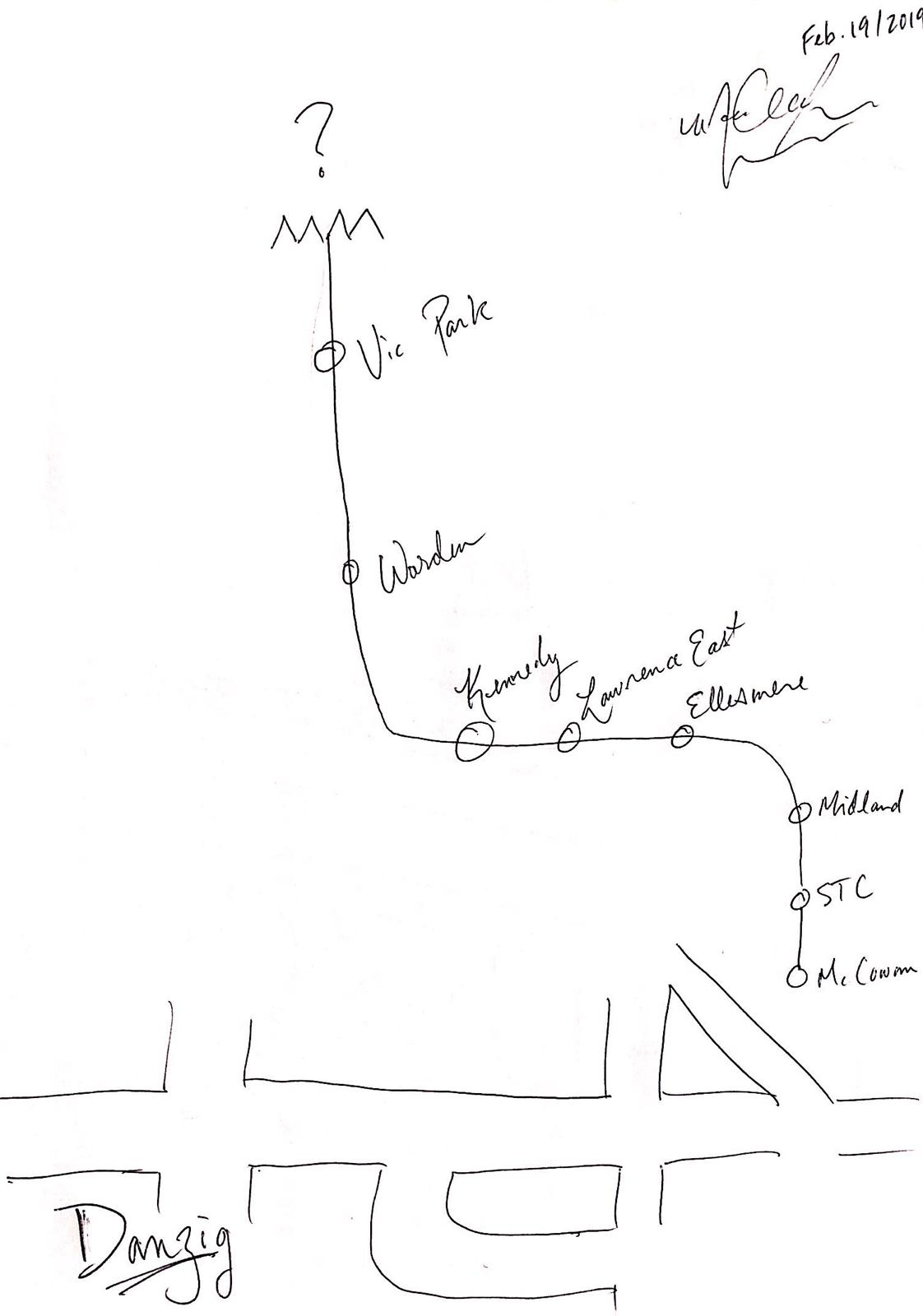

A sketch of what young Adrian De Leon believed Toronto was, based on the TTC stations and places he frequented.

Adrian De Leon is an Abagatan (Southern) Ilokano writer and educator from Manila by way of Scarborough. His first poetry collection, Rouge (Mawenzi House 2018), has been featured on platforms such as CBC Metro Morning and The Scarborough Mirror. Adrian is a Fulbright Scholar, a PhD Candidate in History at the University of Toronto, and teaches English at the Scarborough campus. For the past ten years, he has taught at his family’s Filipino martial arts gym in Scarborough. In Fall 2019, he will join the University of Southern California as an Assistant Professor of American Studies & Ethnicity.

Natasha Ramoutar is an Indo-Guyanese writer by way of Scarborough (Ganatsekwyagon) at the east side of Toronto. Her work has been included in projects by Diaspora Dialogues, Scarborough Arts, and Nuit Blanche Toronto and has been published in The Unpublished City II, Room Magazine, Living Hyphen, Understorey Magazine, and more.