Interview by Kyle McKillop

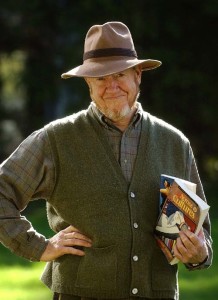

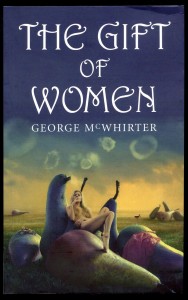

What befalls the outsider? Poet, novelist, and short story writer George McWhirter has often examined the newcomer and outsider and how they manage in an unfamiliar or disdainful society. McWhirter’s first-ever published story, “The Extinction of H”, appeared in PRISM’s 8:3, Spring 1969; he later became the Advisory Editor for the magazine. He was the first Poet Laureate of Vancouver and his most recent book is the collection The Gift of Women from Exile Editions.

George invited me to visit the home he shares with his wife, teacher and writer Angela Mairéad Coid, not far from the green space of the UBC campus in Vancouver. Drinking Earl Grey in the comfort of his living room, our conversation led us to The Gift of Women, and his life as a writer and teacher.

In your latest collection, The Gift of Women, many of the stories feature strong female characters who are sexually and socially empowered. What draws you to that characterization?

I’m part of the generation where the men went to work in the morning, came back at night, and who were we brought up with? Even when we boys played in the street, the women in Belfast were in the doorways watching us. So women were arbiters and the biggest influence we had.

The last year of the war, 1944, we lived in a small place called Carnalea. Between two bungalows were basically about thirty-five people and this is because of the Blitz. And it just so happened all of my older cousins were girls, so I went to school with this mob of young girls. I was stuck on the bus and I was their toy. I was taken to school and then I would escape into the glen at Crawfordsburn. I was very good at buggering off. So how else should I write about them? As soon as I think, there are women in my thinking and in control. Lifting and laying men, like Meta with her dolphin man in “Arrivederci”. My wife [Angela Mairéad Coid] just continues that with me.

Speaking of Meta, your characters, like Meta and El, aren’t invested in anybody else’s opinions; they’re living their own lives.

They go their own way. They’re Ulster women. My mother was the same way. She ran everything. And the same with me and Angela. I would have never left Ireland if it hadn’t been for Angela. I’m one of those guys, you put me there I’ll stay there.

One of the great snowstorms during the war when I was 4, all the girls made an igloo and they put me in. They couldn’t get into it because they were a bit too big. They buggered off and played and then they forgot all about me. I don’t know why it fascinated me, but I just sat in there. I can remember the walls of it now, and there was enough light coming in. They went looking for me all over, down the river and in through the woods, and eventually they decided to come back and look at the igloo and there I was. And one side of me is like that: go nowhere until the girls or the women fetch me out. Most of the women in my life and my fiction go their own way and come back to see if the men are still there where they left them. As to opinions, as a friend lamented of the women we grew up with, “Say what you like, they’ll hear nothing that doesn’t suit them.”

One of the great snowstorms during the war when I was 4, all the girls made an igloo and they put me in. They couldn’t get into it because they were a bit too big. They buggered off and played and then they forgot all about me. I don’t know why it fascinated me, but I just sat in there. I can remember the walls of it now, and there was enough light coming in. They went looking for me all over, down the river and in through the woods, and eventually they decided to come back and look at the igloo and there I was. And one side of me is like that: go nowhere until the girls or the women fetch me out. Most of the women in my life and my fiction go their own way and come back to see if the men are still there where they left them. As to opinions, as a friend lamented of the women we grew up with, “Say what you like, they’ll hear nothing that doesn’t suit them.”

When you left Ireland and came to British Columbia [to Port Alberni, a small town on Vancouver Island] did you feel like an outsider or did you quickly feel like part of the community?

No, that’s one of the reasons why I took the job. My wife, Angela got a job there first in Port Alberni. School District 70 needed an elementary school teacher and gave me a job as well [teaching high school]. Straight away, after getting off the bus down by the little harbour in Port Alberni, I was met by Mr. Jameson from the school board, and the first thing he did—you’d think I’d be taken to a big formal interview—no, he took me up to Woodward’s [a now-defunct local department store chain]. He said he was going to buy something, so he brought me along. Not a word had been said about anything to do with teaching.

As to community and feeling part of it, every Friday we teachers would go down the hill to the Barclay pub, which was right beside the pulp mill on the Somass River. All the men would pour out of the pulp mill; the women would come along to join them. By evening, it got really wild. Port Alberni had no pretensions, and you don’t integrate in places that have got pretensions that you are apart from.

Port Alberni adjusted my whole approach to things. It was very level, very democratic, very easy-going.

As for the writing community I became part of—while I was in Port Alberni, a bunch of writers came over from UBC and they were as friendly as the people in Port Alberni. Andy [Andreas] Schroeder, Red [Charles] Lillard, Eric Forrer, George Payerle: they came over; next thing, they’re sleeping on our floor, letting us into their lives while we gave them a place to lie. Of course we were all equally egotistical eejits, but socially open and most of us open to all kinds of different styles. That was the great thing about that first group of writers that descended upon us and adopted us. They were all trying something different.

In this collection of stories, how did you manage the dialect? How do you go about capturing such varied voices?

I’m fascinated by voices. To tell you the truth, the Irish are ferocious mimics; they make fun of everybody. We could pick up the smallest difference in inflection, use it to pick out where a person might come from in Belfast or elsewhere in Ireland. Like when we used to go swimming in the Irish national championships, the lot from Cork would imitate our Belfast accent and we would imitate the Cork accent and we would ask each other, Whose is the uglier?

Accents, the way people from other parts of the world speak English—I absolutely love it. What they do with phrases, what they cut out, where their stresses fall on verbs and nouns and everything in between gets a bit mashed—even verbs get a bit mashed—but there’s always something lovely to listen to.

We used to go to Acapulco from Mexico City when I was collecting poetry for an anthology (Where Words Like Monarchs Fly, Anvil Press). We would go to Mexico City to see José Emilio Pacheco, Homero [Aridjis], and Gabriel Zaid and others. Five men and five women poets. We would go to Mexico City for ten days or so—that’s as much as we could stand—and then we would head for Acapulco, and in the eighties Acapulco was absolutely full of French Canadians. I just adored them and when they would start speaking English, I would just try to absorb that. It comes out in the story, “Tennis”, in The Gift… There’s always editing [in recreating dialect] but the primary editor is the ear. [In translating] I had to become this or that Spanish poet or storyteller in English, and that’s where I learnt a lot about dealing with various voices.

Speaking of translation, I wanted to ask you about the voice of Don Matteo, a Mexican labourer in the story “Lonely Rivers Flow to the Sea, to the Sea”.

He [the person Don Matteo is based on] was a terrible alcoholic. But he worked in the cane fields and on his way home there was a pulquería [bar serving fermented agave sap] on the other side of the highway. He got as far as the pulquería and then the family sent me to carry him home from there. “You go, you’re strong enough,” his daughter said. And so I went and carried him across the highway, brought him home and laid him in the bed along with all the crates of Coca-Cola. They had a television, crates of Coca-Cola, and a dirt floor and bed in the family jacal.

So I listened to the family, to their resentments and complaints, and how they spoke in Spanish, and in the Don Matteo story I translated it into how it would be in English. Snippets, longer bits of dialogue and talk in Spanish stick in my head and roll over into English looking for a decent rendition. One of [the men in Cuautla] said the most interesting thing. This is in the Café Universal, and they’re all there sitting playing with their dominoes and I’m chatting to them and watching out for the scorpions in the cracks. I say, “Oh, Angela will want me. I have to go; I can’t chat anymore.” So he says “Yo soy la muñeca de mi mujer, también.” I am my wife’s doll, too. The Spanish is lovely: muñeca de mi mujer. I couldn’t get that into Don Matteo’s mouth, but one day I’ll find a person and a place for it in a story.

For a Mexican man to say what my friend said in the Café Universal is rare. The Mexican men we were close to proved to be quite different. They were very socially minded. Their wives ran their own businesses and the men ran their own businesses. Which was interesting for me because my mother had been a terrific business woman but my father was a disaster as a partner for that. One minute he was a hard man, the other he was a soft soul who would give everything away. In The Gift of Women, you’ll find a lot of my father in Gonzague [in the story “Cup-W”] and a lot of my mother and wife in Gonzague’s wife. However, as the story tells, Gonzague’s wife saves him from himself.

What role did teaching play in your own growth as a writer?

Talking about reading and an audience, it played a really big part. One of my gifts that I got from family was the place that we had by the sea in Carnalea and I could go and retreat there. And so in one way I was always able to bugger off from things. That wasn’t necessarily good. There was a lot of things I didn’t face up to because I could just go to Carnalea.

It wasn’t until the end of my first year teaching in Kilkeel, and we were getting married, that I faced up to the fact that I have to really do things for other people—and teaching is part of that, doing something for somebody else, maybe before you could even do it for yourself. And so I began that whole process of teaching myself to teach others. Teaching really started me to think about other ways of performing and actually facing an audience.

Kyle McKillop collects concussions and teaches secondary English in Surrey, British Columbia. He is also a Master’s student in UBC’s Optional-Residency Creative Writing program. Find him online at kylemckillop.wordpress.com.