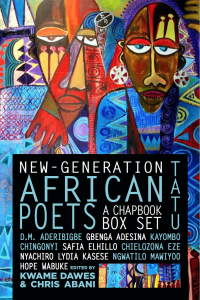

Former PRISM poetry editor (2014-15) Rob Taylor sat down with Kenyan poet, and recently named Brunel University African Poetry Prize finalist, Ngwatilo Mawiyoo to discuss her new chapbook “Dagoretti Corner”. “Dagoretti Corner” is one of eight chapbooks included in “New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Tatu)” (Akashic Books/APBF, 2016, ed. Kwame Dawes and Chris Abani).

Mawiyoo launches “Dagoretti Corner” in Vancouver on April 4th. Read on, or click here, for more information.

Fatigue – Ngwatilo Mawiyoo

Kwale County, February 2013

Shivering, you have walked to your mind’s edge.

Walk no further. Leave the question

of these severed blood relatives,

leave it with the mango tree. Can it bear

fruit when it is too young to shade its own stem?

Can it save those called lazy, sinful, thief, witch;

those who named them so?

Let the tree answer, let it live or die. You need

yourself more than questions need answers.

You cannot bend the head of one,

make him lick the wound of another,

knowing the wound and the tongue are septic.

Let God do it. Let Him manure the tree

if He wants. Let Him hold up the branches,

whisper the heavying twigs strong

so the fruit does not tear green

as is happening to you even now.

Let Him stop the rain and shine the sun.

You, let the tree alone.

The genes of different seeds have already combined

though they accuse and sentence each other maniacally,

long after the graft has taken,

after the sap of one is the sap of the other,

is you. You must let the tree answer. You

do not need the answer to survive.

(Akashic Books/APBF, 2016).

Reprinted with permission.

“Fatigue” is tagged with the date “February 2013” – the month before Kenya’s 2013 Presidential Election, the first since the violence of the 2008 election. That 2008 election, its violence and ethnic tension, and the subsequent violence and instability Kenya has faced (including the al-Shabaab attacks at Westgate Mall and Garissa University College), sit front and centre in Dagoretti Corner (though perhaps, as I consider your publication timeline, Garissa only looms somewhere in your editing process). Because of this, I came to view “Fatigue” as the cornerstone poem in the collection – both for its subject matter, and its spirit. It is simultaneously hopeful and hopeless, empowered and disempowered (in this and other ways it reminded me of Muriel Rukeyser’s “Ballad of Orange and Grape“).

I know the poem does a great deal of the talking for you, but can you add anything in prose about how you felt in February 2013, readying yourself for the election?

Thank you so much for giving these poems such close attention. I really appreciate that.

February 2013 was a difficult time. I’d traveled to Moyale on Kenya’s northern border with Ethiopia, and then to Tiwi on the coast near the southern border with Tanzania. If any communities with a sizable population are marginalized in Kenya, it’s those who live along the coast and in the north. They are largely Muslim, and have been so since before the missionaries came; Kenya’s political elite thinks of itself as Christian. There are also real and perceived cultural differences between the political elite and northern and coastal groups, and real unjust actions that go back three presidents and various colonial administrations. These problems aren’t ancient history, they are present enduring sources of pain exacerbated by everything at election time. I was also worn out from the This Kenyan Life project, and in a place of fatigue, and hopelessness. At that moment it was clear to me that the country could not be fixed, and trying to fix it was less important than surviving it all. I guess the poem speaks to the generation that’s grown as a product of the mess, and has a chance to fall from the tree, so to speak, a chance to become something else, if only it could reach a point of maturity while still on the tree.

Ah, that sets me up well for my next question! As I spoke of above, “Fatigue” fits very well within the major themes of Dagoretti Corner. It also fits within a smaller theme I found running through the book: tree poems (esp. mango trees)! In your opening poem, “Portrait”, grandfathers who are “in the ground” are described as being “bone and smoothed tree.” In “The Rain is Late” children “wring mangoes from the tree” and give them to the speaker, and then on the next page “Ngoma for Mango” explores the mango’s “salty-lemon-masala-sweet”. After all that,”Fatigue” arrives with its gene-mixing, grafted mango tree, which seems to hold within itself an entire nation.

Could you speak a little about what the mango tree represents for you in your poetry? Does it change from poem to poem, or does it carry for you a relatively consistent emblematic power?

I suppose my relationship with mangoes and mango trees is a living relationship. It’s become a tree that means childhood and home, but also holds the possibility for corruption, sensuality, joy and betrayal. When writing from diaspora, mangoes are especially prone to show up in my writing because that’s when I’m most sick for them! But trees, more generally, lend themselves to poetry. There’s a history about how they came into a place, how they survived, what they signify or are associated with in the community where they exist. When I haven’t been obsessed with mangoes, I’ve been obsessed with Jacaranda trees, which are very iconic of Nairobi (and its colonial history).

You mentioned above your This Kenyan Life project, in which you visited 20 different families, in 20 different parts of Kenya, over 200 days from 2011 to 2013. Could you speak a little about that project? To what extent is Dagoretti Corner a direct result of those 200 days?

I have to begin by admitting that while 200 days was the intention of my This Kenyan Life project, I was only able to complete 7 different parts of Kenya in 70 days, although it became more than 7 families. I’m still making peace with barely getting to half, even though I’m very proud of the 70 days I did accomplish. The basic idea of This Kenyan Life was to be able to meet a diversity of families living across rural Kenya, live with them, work alongside them as far as was possible, witness their joys and sorrows, listen to their concerns, and ultimately see how similar or different Kenyan families are from each other. In the context of the violence of 2008, which was ethnically and politically motivated, I thought it was important to seek out Kenyan people outside of the rhetoric, at the family level, and possibly write an experience that was authentic to their experience, and could offer an alternative narrative to Kenyans and the outside world.

You’ve certainly done that, for those of us looking in from outside. On that theme: in the title poem you write “I am always / on the edge of things.” which got me thinking about the insider/outsider dynamics of your own writing life. You write a great deal about Nairobi and Kenya, and do so both as an insider (when talking about your own life, the city of your birth, etc.) and as an outsider (when traveling to other towns and villages in This Kenyan Life), and you publish those poems both inside Kenya and internationally (where they are bound to be interpreted at least somewhat differently). On top of that you’ve written, workshopped and edited many of these poems during your Undergraduate and Graduate degrees in North America. In other words, it seems to me that you’ve written about, and from, and to, a lot of edges. And it’s meant a lot of kaleidoscoping between the known and unknown, both for you and your readers.

Could you speak a little to this sensation of being so often “on the edge”? In what ways, if any, do you think it’s strengthened you as a writer? And what keeps you tethered as a writer, and as a person, throughout it all?

It’s an astute observation, Rob. Kenya itself is incredibly diverse, whatever anyone tells you. I knew what it was to be an insider/outsider even before I ever left Nairobi. My trouble is I keep moving myself around so that sometimes I’m part of an inside group, sometimes I’m rotating through outsider spaces. It’s tedious in that I find myself always having to define and redefine my identity and its meaning in the particular community I’m living among at a given moment. And it’s hard to be consistent especially the more you know about the “other,” and come to understand them. As a writer I try to find language to write across these spaces as honestly as I can. How do I stay tethered? I don’t know.

More specifically, for this collection, you worked on (and “workshopped”) many of these poems while pursuing your MFA in Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia. How do you think working on these poems in a place so distant (physically, but not just) from Kenya influenced the collection? More generally, in what ways do you think Dagoretti Corner would have been different/the same if you hadn’t traveled to Vancouver or pursued your MFA?

Workshopping the poems in Canada forced me to think about how “outsiders” (read: non-Kenyans) would hear the poems. This was both useful and burdensome. I think by the end of it I learned when it was important to me/the poem to articulate place in a direct way, and when I would let the poem just be. It’s occurred to me that if I’d been writing from home, there may have been more poems like “Fatigue” actually, perhaps distance truncated the frustration I felt.

Interesting. Yes, I agree that it’s easier to be forgiving about your home when you’re away from it. Distance also numbs certain pains, and heightens others. I remember, when the Westgate Mall attack happened, feeling a distant form of sadness, but then, when I heard that Kofi Awoonor – a poet I’d admired for years – had died in the attack, it became this visceral, personal pain that took a long time for me to shake off.

“Site of Sorrow”, your poem about Awoonor and Westgate Mall attack opens with an epigraph from Awoonor: “Something has happened to me / the things so great I cannot weep”. When I read that I could hardly breathe, and all my memories and pain of that day came rushing back to me. I remember the shock and horror of it, of course, but mostly my deep sadness at losing such a vital and influential poet, one whose role could not be easily replaced. And also, learning the news from North America, a sadness that the loss the African poetry community was sharing wouldn’t be felt nearly as hard in North America, where Awoonor was far less well known.

I feel like a good way to honour Awoonor is to draw attention to others like him who are still writing and teaching and guiding the next generation. As such, can you recommend a poet or two who are already well known to African poetry audiences, but may be unknown to North American readers? Poets, perhaps, who shaped and informed your writing in the way that Awoonor did for many?

As far as I can tell we’re not yet at a place where “African poetry audiences” are necessarily aware of poets across the continent. Some cities/countries are fortunate to have poets from across the continent and around the world traveling in and out, and may be more aware of a range of people working in the form. But when a poet of such range crosses your path, your path becomes narrower and more expansive. I have to say Kobus Moolman has been a favorite for several years now. He actually just won the 2015 Glenna Luschei Prize so hopefully North American audiences will have a a better chance at knowing his work. In East Africa and Kenya we just lost Marjorie Oludhe who was a mainstay in poetry (and fiction) for many many years. Actually she also wrote a beautiful piece that’s in the new Kwani? for Kofi Awoonor. 2016 is also the year we’re remembering Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek’s influential work Song of Lawino, which most Kenyans know and probably had to study in school.

Yes, you’re right – when I say “African poetry audience” I’m really meaning “Accra/Lagos/Nairobi/Cape Town audience.” It’s good to be reminded of that. Speaking more specifically, then: I know you haven’t been home in Nairobi all that long, but I’m interested in a little “status report” about the current moment in Kenyan poetry. Have you noticed any differences in what’s happening now compared to when you were in Kenya pre-MFA? What elements of the Kenyan “scene” (oh how I loathe that word!) do you think are currently the strongest? What areas could use more attention?

Our schooling and opportunities to get involved with poetry have tended to focus on performance sometimes at the expense of the text upon which any performance might be based. Performance still seems to be a strong value for us, although I have come across more poets who are more principally interested in their texts, and in building a body of work. The level of commitment to craft is growing, and things that people are doing with language (in terms of English, Sheng, Kiswahili etc) continue to be interesting.

Can you give us some details of your Vancouver launch for Dagoretti Corner, on April 4th?

I have a reading at UBC’s Green College for Monday, April 4th at 5pm! Tell everyone to come! It’s essentially a pre-launch for the chapbook, since the box-set becomes officially available on April 19th. For me personally it’s a celebration of my time at UBC, a marker of my time in the MFA program and living at Green College. I’m grateful to have some very special guests with me, including 2016 BC Book prize nominee Raoul Fernandes and Thursdays Writing Collective founder and convener Elee Kraljii Gardiner, whose highly anticipated book serpentine loop is just out this spring from Anvil press. It will be a chance to gather together, listen to some poems, possibly make off with some books, and have a good time.

Can’t make it to Ngwatilo’s launch? Starting April 5th 2016, you can order a copy of New-Generation African Poets: A Chapbook Box Set (Tatu) from the Akashic website. Or, if you must, you can order it on Amazon.

You can read more of Rob Taylor’s interviews here.