Review by Francine Cunningham

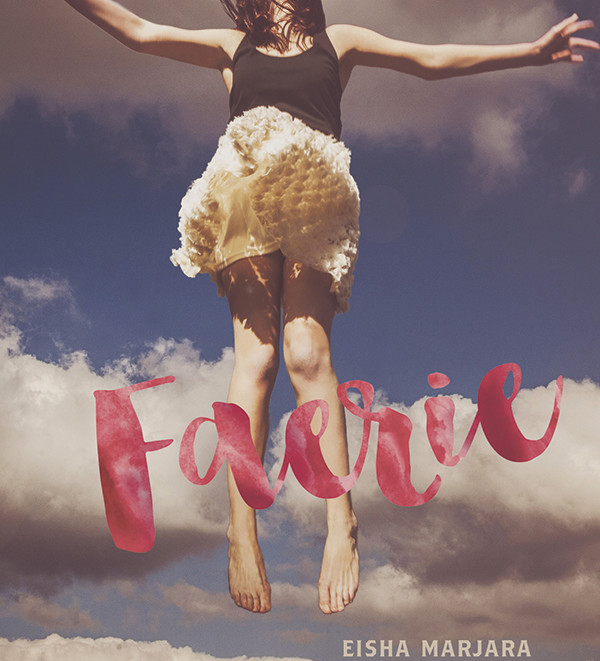

Faerie

by Eisha Marjara

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016

Faerie, by Montreal filmmaker Eisha Marjara is a Young Adult (YA) novel that tackles tough issues head on and does not back down from the reality of a young woman wrestling with a debilitating eating disorder. Lila, a young South Asian woman in modern day Canada struggles in the depths of anorexia nervosa. We are given a glimpse into the lives of Lila and her family as they deal with the devastating effects of her illness.

Faerie gives a literary voice to a historically underrepresented group in Canadian literature. As an Indigenous teenager, I know how difficult it can be to find books that speak from our unique point of view with characters that relate to our experience. Once handed a copy of Lynne Reid Banks’ Indian in the Cupboard by a teacher excited it had an Indian character in it, I am delighted (as a teacher now myself) that I can offer books to my Indigenous students filled with characters they can relate to, and I only hope more get written. For South Asian readers, especially young readers, to be able to pick up a book that is written with such nuance, that speaks with heart and integrity to Marjara’s experience, is wonderful. As I read Faerie I could see how Marjara was butting up against popular YA fiction and an historical lack of diversity. “Anorexia has been considered a white girl disease, and I often wondered how I fit into that as a South Asian woman,” Eisha Marjara said in an interview on CBC Books. Marjara’s voice joins an explosion of diverse voices and point of views in YA literature right now, tackling issues like suicide and mental illness and giving readers a safe space in which to start a discussion about what it means to live with mental illness.

Marjara handles this story with delicacy; speaking from her own experience and translating it to a believable fictional character whose story is heartbreaking. Lila is the daughter to Punjabi immigrants and, Marjara effortlessly opens the door to their household and to the struggles of this family as they try to hold on to their cultural traditions under the influencing force of Canadian culture. You see this most clearly in the storyline of her older cousin who has a great impact on how Lila sees herself and her body image. Dressing provocatively and fighting with Lila’s father about boys, music and rules, her cousin eventually leaves the family home, leaving Lila alone. Lila often compares her soft body to that of her cousin who has all the right curves and isn’t afraid to show them off.

You also see Lila’s struggle as she longs for her mother’s traditional cooking but at the same time cannot force herself to eat that food as it contains too many calories, too much fat, too much of everything she must deny herself. Her mother, on the other hand, only worries more, and tries to show her love for her daughter by cooking more food, loading Lila’s plate with the tastes she was brought up loving. But as much as Lila longs for it, in the depth of her disease she must deny herself this part of her culture, and this part of her mother’s love, in order to attain the perfect skeletal frame she is chasing after.

While in the depths of her disease, Lila escapes the enclosing walls of her mind and body by imagining herself as a beautiful faerie, one who is free of the earth, free of weighted flesh, beautiful, and in Lila’s mind—something as opposite of herself as she can get. “I weighed exactly ninety-nine pounds. My dedication to my calorie diary was finally working like a charm. My heart beat accelerated, time slowed down, and nature began to relinquish her hold on me. I was euphoric. My clothes slipped over me like a breeze, and without the cumbersome folds of flesh, there was a space for air, for wind. My feet were parting the earth. The walls of the chrysalis disintegrated. The faerie slowly spread her raw young wings. She was free. She was me.” (66) Lila uses the faerie as a source of inspiration, a place of mind to go when she needs comfort but who is ultimately killing her.

The adults in this story are often portrayed as indifferent. The staff at the hospital where Lila spends a great deal of her time seem to be quite dense and lax about her disintegrating health. A fellow patient however, is a great example of how the bonds of friendship can help heal a person, and in the end provide the shock to see how bad her disease really is and how much it is hurting her family, and herself.

There are many moments in this book that made me flinch, where I had to turn away; the descriptions of her body’s appearance, the suffering she puts herself through to reach an unattainable perfect weight were disturbing, real and raw. This book will be triggering for some people and will be enlightening for many more as the curtain is drawn back from the truth of what it is to live with such a debilitating disease.

My hope for this book is that it gets into the hands of young readers who are struggling with these same issues. Lila is so honest that I feel many people will be able to relate to her and hopefully come to some of the same lessons that she does about her own illness and embark on the same path to healing.

Francine Cunningham is an Aboriginal writer, artist and educator from Calgary, Alberta currently residing in Vancouver, British Columbia. Francine has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing from The University of British Columbia. Her work has appeared as part of the 2015 Active Fiction Project in Vancouver, in Hamilton Arts and Letters, The Puritan, The Quilliad, Echolocation Magazine, Kimiwan’zine, nineteenquestion.ca and The Ubyssey.