Review by Deborah Vail

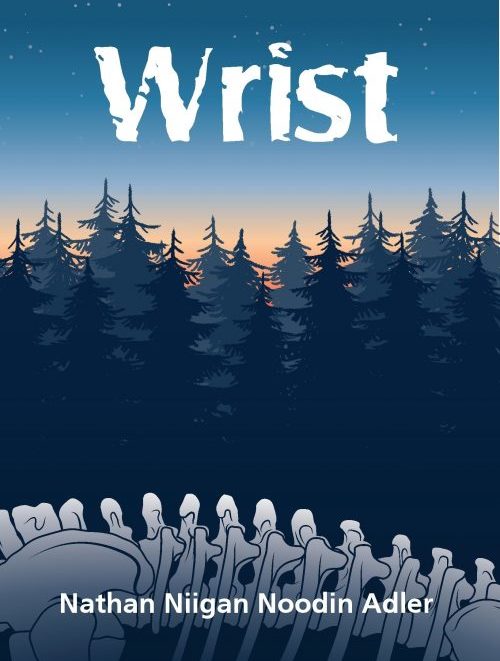

Wrist

by Nathan Niigan Noodin Adler

Kegedonce Press, 2016

Nathan Niigan Noodin Adler is a writer and artist who works in many forms including audio, paint, film and glass. He is currently a candidate for an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia and is a member of the Lac Des Mille Lacs First Nation. His debut novel, Wrist, is a layered narrative of horror, cultural exploitation, science, humour and Indigenous legend. The story follows a boy named Church and his faithful companion, a knife named Religion.

It begins with his grandmother telling him that he is descendent of the wiindigo, an Ojibway monster that has an insatiable appetite for human flesh. This monster tore apart Church’s great-grandfather and ate him limb by limb while his great-grandmother crouched in a corner and watched. To save her own life she succumbed to the wiindigo’s other insatiable appetite, sex. Church is taught to control his hunger, never eating too much or too little and to always keep his monster side hidden. The author invites the reader to interpret this hunger as anything that consumes a person. The novel opens with a paraphrase of Lionel Shriver from CBC Radio. “Often we are driven to eat to fill other hungers that can’t be filled with food…Loneliness, sadness, trauma. An emotional hollowness.”

As his story unfolds, Church is chased by monsters of another world, vampires hired to help a large oil company acquire the land that he has inherited. The irony is well paced and delivered. His grandmother warned him of monsters from afar. “Immigrants brought their own monsters with them. Their own hunger, their own forms of wiindigo.” (209)

Throughout this compelling story, Church makes keen observations about the world he lives in. “Church supposed colonization wasn’t just political or geographical; it crossed all boundaries down to the cellular level; atoms, genes, and the deadly encroachment of disease.” (383)

Underneath this story of horrors is an even greater and more poignant one. That of an Indigenous boy who lives in a constant state of fear, doubt and loneliness. Church’s non-Aboriginal father who is supposed to teach him what it’s like to be human uses him to con people. His mother, who is that much closer to the wiindigo ancestor, is trapped within her mind and never speaks.

Church always wears grey and goes unnoticed. This skill is challenged when a new boy named Geoff arrives at his school and bullies Church until they fight. The tension between them is so great that the reader is cued to expect more. Years later when they meet again Geoff is kind, protective and generous. Both loners, they reluctantly develop a romance that is gentle and heartfelt. In a tenderly written scene Church shows Geoff his burn scars that he got while sniffing gas as a young boy. Gas fumes had ignited and one of the other boys burned to death while Church watched.

“These scars were old and long healed, but they almost seemed to bleed with their immediacy, articulating years of pain. If he were a book, the pages would bleed. Geoff could read Church’s life history on the terrain of his body, and it all told the same story: a road map detailing a lifetime of pain.” (335)

This story is wrought with sorrow but laced with lyrical descriptions of the natural world and the intelligent reflections of a young boy just trying to survive.

Braided throughout the narrative are the historical accounts of two competing British archeologists who excavate dinosaur bones near Church’s ancestral lands. It’s 1872 and a Caucasian doctor travels with them to study the wiindigo psychosis that makes a person crave flesh and experience relentless hunger. The doctor refuses to believe in the Indigenous healing methods until he too succumbs to this psychosis and must rely on tradition medicine to survive. The reader is left to wonder if wiindigos truly exist while Church maintains that, “Real is real, regardless of whether you can see it or not.” (391)

There are graphic and visceral descriptions of brutality but Church’s humanity is ever present even when his wiindigo side begins to surface. Humour and the use of metaphors make for a tongue-in-cheek read at times.

Told predominantly through exposition with Ojibway references throughout, this novel feels as if someone is recounting a family story—a story wrought with warning and wisdom. At times the writing is repetitive, repeating facts that have already been told and there is a tendency on the author’s part to refer to one thing to describe another. If the reader is not familiar with the reference, the image is lost. For example, “His enemies were like Doctor claw, the bad guy in the Inspector Gadget cartoon….” (293)

Furthermore, the author’s voice hits the page with the many scientific references that are dropped into the narrative and pull the reader out of the action. When Church nearly drowns and Geoff must breathe for him, the chemical makeup of oxygen is described. “Air is 21% oxygen, air that is exhaled has about 16% Oxygen which is more than enough to keep someone alive, since every breath only extracts the 5% it needs.” (400)

Nevertheless, Wrist is a novel that can absorb a few stylistic challenges. It is a thought-provoking, original and daring take on monsters, pop culture, religion, heritage, exploitation and what it means to be human. This unique debut novel challenges the reader to question stereotypes and assumptions and to think outside the box. It stays with you long after the last page.

Deborah Vail writes fiction and creative non-fiction. Her work has appeared in Ascent Aspiration and Canadian Stories. She is currently pursuing her MFA through the Optional Residency Program at UBC.