Nix

Jessie Jones

Desert Pets Press

Review by Andy Verboom

In poetry, myth is usually deployed either as allusion or as conceit. The distinction between allusion and conceit is analogous to how one might treat a very old hammer: Do I display it behind glass in a museum? If so, I intend allusion, feeding on the myth’s aura as it becomes elevated in a different setting. Do I take it in hand, use it like the tool it still is? Then I intend conceit, trading on the myth’s narrative resonance. In either case, the myth is an object.

Jessie Jones’s debut chapbook, Nix, demonstrates a much rarer third way. Rather than wielding the old hammer, Jones lets it talk, acting as its interlocutor and scribe. To become an object in the face of myth — to quiet one’s authorial intentions — demonstrates an uncanny, temporality-rattling, museum-demolishing perceptiveness.

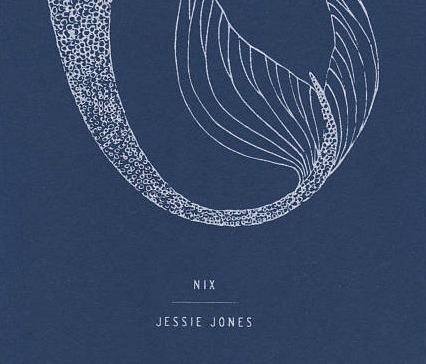

“Nix” means “nothing,” of course, as well as the act of nullifying or excluding — as when, Jones writes, in the endless pursuit of “Self Improvement,” you “[n]ix the bread…. Pace treadmills like you’re on hot coals / so the calories burn.” But Nix’s cover illustration also invokes the nixie, neck, or nokken — a man-seducing-and-murdering, child-abducting-and-murdering water witch or river mermaid. What first appears to be the body of a fish, most of its head falling outside the frame of the illustration, resolves more clearly as the fishy tail of a mermaid, her human half exiled but for the trace of a cartoonish navel. This “nixie” is connected to “nix” by way of shared etymological roots meaning “nude” and “to wash,” the latter of which carries particular mythic connotations regarding the male gaze.

What Jones perceives in “nix” is not an etymological riddle but a complex key to a present in which that old male gaze has mutated horribly into a patriarchal surveillance state and misogynist self-surveillance market. Nix’s first poem, “The Fool,” restructures the mess of “nix” into a basic formula: to surveil is to denude is to nullify agency.

[…] I can move like a bundle

of kindling through the city because I am—

all day I wait for a bit of friction

to transform me. Pretty keyhole,

french braided maiden, the cup trilling

under a finger signing o’s […]

I want to be seen. Behold my keen periphery

where everyone is doubled-

over in love with me.

Where Athena strikes Tiresias blind for watching her bathe or Diana sets Actaeon’s own hounds on him for the same, this ostensible “fool” enacts her own phallic eruption, her desire for others’ desire running down her head

[…] like a cartoon

yolk. It wants to live. It wants to be written

in a book. It is ready to be naughty and caught.

The best poems in Nix are persona poems like “The Fool.” Jones’s personae don’t simply diagnose the seductress/monster, Madonna/whore, object/agent dichotomies of misogyny. Instead — comprehending these dichotomies as absurd machinery for shuttling women’s bodies between either/or — they seize the controls and remake themselves as both/and. The results are often satirical but never without a sincere nod toward the posthumanism of Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto.

Juxtapose these poems — each a bit like Tilda Swinton doing a stand-up routine inspired by Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin — with poet Mary Downie’s treatment of the nixie in her children’s book Jenny Greenteeth: that water witch, blighting Toronto’s Beaches area with her naughty breath, is bested by a young toothpaste-wielding boy. Another fable about the behavioural regimentation of female bodies, about reclamatory masculine agency.

Like its patron monster, Nix is marked by a striking aesthetic split: eight of these ingenious persona poems pair with eight poems that hinge instead on the second person. If the “I” poems are the deceptively comprehensible, psychologically complex human half of Nix, then the “you” poems might be the alienating, fishy tail. The former are conceptually intricate, subtly enjambed narratives. The latter are both more associative and more confrontational. They would be effective in performance, but on the page, they are bulked with internal near rhymes and irregular, syntax-overwhelming rhythms. They seem more concerned with running out of breath than coiling it up. Crucially, their confrontational and implicating “you” often falls short of its target, landing more like poetry’s dreaded self-distancing “you.”

Were Nix’s structure split at the waist like a mermaid (“I” poems in the front half, “you” poems in the rear), I’d be confident in the above critique. But the arrangement of these two species of poem in a mosaic (a structural rejection of patriarchal dichotomies) almost makes me believe that Nix anticipates this overplayed critique — anticipates that a male reader would assert a woman’s more confrontational poems as less impressive in their execution and more obvious in their tricks.

So let me say this: I deeply enjoy feeling outwitted by a collection. And despite my not particularly enjoying a full half of the poems in Nix, the other half puts the chapbook on par with some of the strongest work on similar themes by poets such as Katherine Leyton and Stevie Howell. I will be going out of my way to keep up with the work of Jessie Jones.

Andy Verboom, from subrural Nova Scotia, lives in London, ON, where he organizes the Couplets collaborative poetry series. His poems have won Frog Hollow’s Chapbook Contest and Descant’s Winston Collins Prize, and have been shortlisted for Arc’s Poem of the Year. His chapbooks are Orthric Sonnets, Full Mondegreens, and Tower.