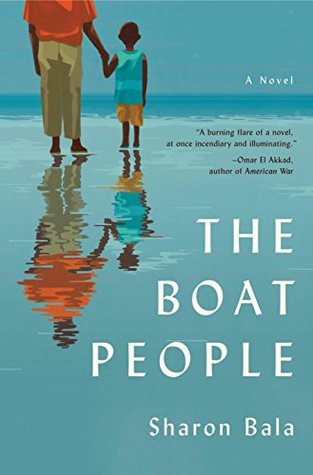

The Boat People

Sharon Bala

Penguin Random House

Review by Anjalika Samarasekera

In the second half of The Boat People, a Sri Lankan immigrant—and former Tamil Tiger—poses a question to his Canadian-born niece: “What do you think happens when you terrorize a people, force them to flee, take away their options then put them in a cage all together?” (230).

The question is the ravaged heart of Sharon Bala’s remarkable debut novel, which chronicles the arrival of around 400 Tamil refugees on the coast of British Columbia in 2010. The refugees have fled persecution in Sri Lanka following the end of the twenty-six-year civil war and have come to Canada hoping for a warm welcome. These hopes are dashed when the Canadian government detains the refugees on the suspicion that some of them belong to the LTTE, also known as the Tamil Tigers, a listed terrorist organization. Eventually, some refugees are released and deemed “admissible” to Canada while others are deported back to Sri Lanka.

At the centre of the novel is Mahindan, a mechanic and single father who flees the Tiger stronghold with a few provisions and his six-year-old son, Sellian, on his bicycle’s handlebars. Bala’s depiction of Mahindan’s first experiences in Canada include a Seinfeldian shower scene and the heart-rending separation of father from son, which exquisitely demonstrates how alienating arrival is, in both big and small ways. It also allows Bala to demonstrate the potential for humour in their juxtaposition. The shower, which Mahindan finds terrifying at first, comes to represent a refuge where he can be alone with his pain:

He stood under the piercing spray, water pouring over his face, camouflaging his tears, his frustration at being trapped, the growing dread he’d made an irreparable mistake, his homesickness and grief for every single person he had ever known and loved, the pain of the water raining down like a thousand knives, all of it mixing together. It was the best time of the day, when he let loose his emotions, face contorting under the rain, his sobs drowned out by the rush, the wails of the other men (322-323).

Priya, a young Tamil lawyer, represents Mahindan at the seemingly endless procession of detention hearings before Grace, the adjudicator assigned to Mahindan’s case. Like Grace and Priya, the reader must wrestle with Mahindan’s culpability for a bus bombing that killed seventeen people. Though Bala portrays Mahindan with a great deal of empathy, she does not flinch in detailing his misdeeds or those of the Sri Lankan army. Her depiction of the shelling of Tamil civilians in the “no-fire zone” during the final months of the war are among the most deftly written scenes in the novel. These scenes force the reader to bear witness to the suffering and straitjacketing that a war as dirty as Sri Lanka’s imposes on its most vulnerable.

At times, the novel felt one-sided. We do not have the benefit of the Sinhalese perspective on the war, nor do we have the benefit of the perspective of Tamils who supported the Sri Lankan army’s actions in the north. But this limitation does not take away from the novel’s impact. We are left with the feeling that no matter who the “winners” and “losers” are, the human cost to conflict is bodies, either scattered in the killing fields of Sri Lanka or crammed into the hull of a decomposing ship. One cannot help but hope that Mahindan and the other refugees are allowed to remain in Canada, no matter what they did in Sri Lanka, because their story of survival is critical to the self-image Canadians like to project: a country of open arms, of welcoming faces.

Bala subverts that self-image through characters like Minister Blair, a Stephen Harper stand-in, and Grace, who would rather keep Mahindan in jail and his son in foster care than risk making the wrong decision. Sometimes, Bala’s attempts to challenge the conservative point of view feel contrived: Grace’s mother Kumi comes across as little more than Grace’s ghost—Hamlet’s father, with his singular message of revenge—rather than a character in her own right. And Priya’s uncle’s transformation from Tamil Tiger into docile, law-abiding Canadian citizen feels a little too convenient. Despite these weaknesses, Bala makes clear that Canada is not as rosy as its red Maple Leaf would have one believe, an insight made glaringly apparent by the novel’s depiction of the flawed asylum process that results in Mahindan’s ongoing detention and separation from his young son.

Throughout the book, Bala displays mastery, especially over her primary characters. Mahindan and the other refugees draw the reader in through their stories, offering insight into what survival means when it’s jeopardized. In a chilling observation of the effects of war on its youngest victims, Bala writes: “Grace scrutinized the girl’s expression, hoping to find some proof, of innocence or guilt, but all she saw was survival.” (164) The Boat People offers the reader a glimpse into another’s survival and in doing so exposes all the ways we take for granted our own.

Anjalika Samarasekera is a former criminal lawyer and MFA candidate. She is at work on a novel set in post-war Sri Lanka.