Olga Holin sat down with our PRISM international Creative Non-fiction Contest judge Jonathan Kemp and spoke to him about his writings and what he is looking for amongst the entries.

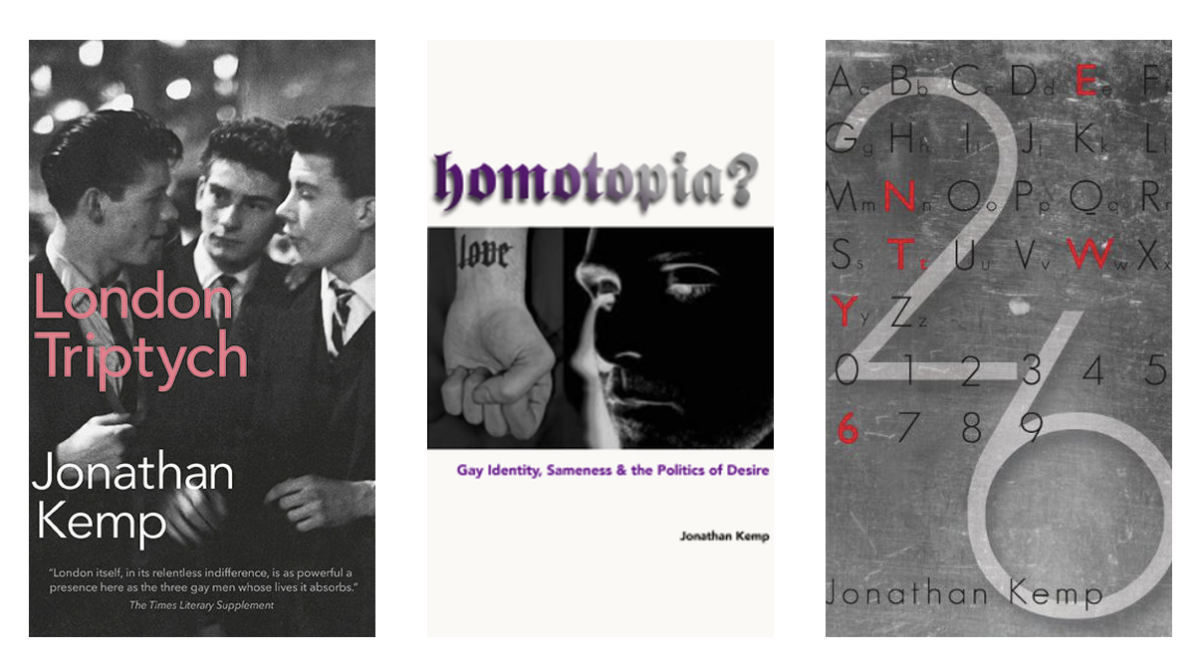

Jonathan Kemp’s debut novel London Triptych (Myriad, 2010) was acclaimed by The Guardian as an “ambitious, fast-moving, and sharply written work” and by Time Out as “a thoroughly absorbing and pacy read.” It was shortlisted for the inaugural Green Carnation Prize and won the Authors’ Club Best First Novel Award in 2011. He teaches creative writing at Birkbeck College. A story collection, Twentysix, was published by Myriad in November 2011, followed by a second novel, Ghosting, in March 2015. His first book of non-fiction, The Penetrated Male, was published by Punctum Books in 2012, with a second, Homotopia? Gay Identity, Sameness & the Politics of Desire, in 2016.

Jonathan, you have a Phd. You have published two novels, a story collection and two non-fiction books. One could argue that your story collection is a collection of long prose poems. What do different genres offer you?

I would call Twentysix a collection of prose poems. I’m very interested in the notion of poetic prose. I was heavily influenced by reading Baudelaire’s prose poems. I’d been a fan of his writing since my early 20s, but didn’t discover the prose poems till I started my PhD. They’re these fragments that fold and weave in and out of the city. In Twentysix I was playing with the idea of a sexual flaneur, someone navigating the city through a series of anonymous gay hook ups. I wanted to do for my queer London what Baudelaire had done for his Paris, if that doesn’t sound too bold a claim. When I wrote those prose poems I’d just finished my PhD in comparative literature so my head was full of Derrida, Deleuze, Kristeva, Lyotard, all those post-structuralist ideas about subjectivity and language. I wanted to interrogate language, destabilize the reader somewhat. I’m planning a sequel, to be called Fiftytwo.

For me the notion of genre is a notion of form. Even of shape? How are you going to say what you want to say?

Do you approach writing non-fiction differently?

The two non-fiction books I’ve published are academic works of theory, one was my PhD thesis and the other my MPhil thesis. I’ve always been interested in theory and queer histories and spent my twenties and thirties in academia, almost permanently studying alongside work and writing fiction, and in the mid-90s writing and putting on plays on the London fringe. These two works of non-fiction, Penetrated Male and Homotopia? were documents of scholarship based on years of research in libraries. I like to think my attention to language is always there, whether what I’m writing is a play, a personal essay, a short story or an academic paper. One of the things that first drew me to writing was the stuff of words. The materiality of language. I still find words fascinating. That we have this medium with which we can attempt to express something we feel or think within us. That we can use it in interesting ways. It’s not simply a tool for communication (though I’m not downplaying the importance of that), it’s also got decorative applications, violent applications, it can be made to perform great feats of imagination, it can enchant us and move us deeply.

What makes a creative non-fiction piece stand out for you?

It’s a really tough question to answer because it’s really a case of you don’t know till you see it, or read it. It might be a question of voice – I want to listen to this person, this tale – or it might be the content, the subject matter. Often, I think, it’s a combination of the two. John McPhee talks about how important structure is to his work, that he spends an inordinate amount of time getting the structure right. In which order are you going to convey your story to the reader? Where to open, where to close? The tightness of the storytelling and the sense of depth that can come with great candour are things I admire greatly. One piece that stood out for me recently was Lily Dunn’s recent piece for Granta. I also really like Maggie Nelson and Rebecca Solnit.

Creative non-fiction is personal, can it be too personal? Where do you think the line should be if there is one at all?

I am a great fan of the warts-and-all mode of grisly confessional, such as the chapter in Edmund White’s My Lives about his Master, detailing a BDSM relationship he’d had. No information is Too Much if you use it properly. I don’t want to read something mediocre that has nothing new to tell me about what it’s like to be alive on a damaged planet. I admire writers with guts, who try and expose and explore something raw, try and say the unsayable. For me it’s a question of self-awareness. I constantly ask myself, why are you saying this? Writing this? What effects might these words have, once they’re out in the world for all to see? As Deborah Levy writes,“To speak our life as we feel it is a freedom we mostly choose not to take.”

Should contemporary non-fiction aim to tackle modern day issues and bring them out into the open?

Yes, and I think contemporary fiction should too. What Ali Smith’s doing is really brave and interesting. It makes contemporary fiction contemporary, vividly so. I’m working on a novel right now that uses speculative fiction and historical fiction to explore some contemporary issues such as gender, climate change and the refugee crisis. It’s not so much to bring these things out in the open – in a very real sense these things are already in plain sight – perhaps more that fiction can offer new, more imaginative ways of engaging with the question of what it means to be a human, here now.

What advise would you give other writers?

Just do it. Then redraft ad finitum and ad nauseam.

Finally, what kind of work do you look for in this contest?

It’s that X-factor really. Something that feels original, fresh, new, a voice that pulls me in and keeps me reading. An intelligence I want to spend time with.

Information how to enter the PRISM international Creative Non-Fiction Contest cane be found here.

Olga Holin is our Executive Editor, Promotions. She is a polyglot, a mix of mostly European ancestry, a writer and poet. She is currently working on a series of Andy Warhol influenced poems called “These Polaroids are Voice-Enabled” and on her first novel. She has recently developed an obsession for blackbirds so she is probably outside now, talking to them, trying to feed them. Follow Olga on twitter.