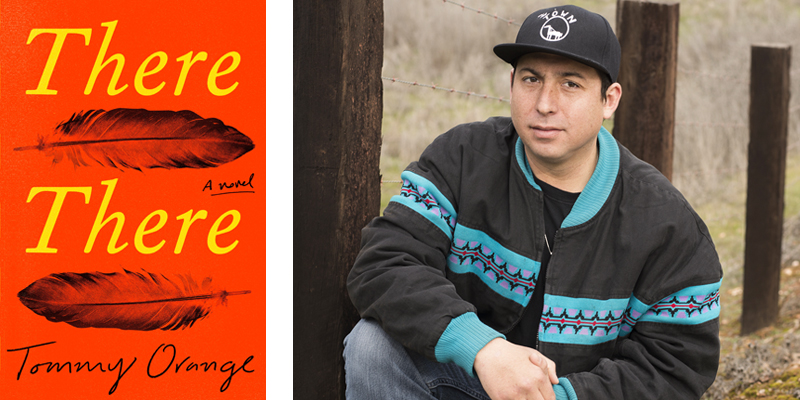

Review of There There by Tommy Orange

Review by Cody Caetano

No need to worry if you haven’t read the dust jacket, because I got the unblinking one sentence pitch of Cheyenne writer Tommy Orange’s There There to hitch the most disinterested readers: twelve exhausted Native folks reeling from one cross-cultural massacre come home to powwow at the Big Oakland Powwow, inside a big metal dome.

They come to work, dance, eulogize, actualize, try their hand at manifesting sobriety once again, take their claim to the prize monies, or fly their drone in to watch the whole thing unfold. The pace leaves us with just enough time to meet the characters before their part ends, wondering with pissed-off excitement when they will return, or if they ever do.

Find here rehabilitation from “solopsism’s recursive, drowning affect” (47), the deadly process of remapping concrete, AA restorative justice decades in the making, and one big ass, intertribal yarn-ball of “mysterious connections,” something Orange poked at for six years, out of his desire to replicate that moment “when you’re reading and get the feeling someone has been inside what is secret. To open up the idea things can change.” This is a novel that demands change from its reader and characters.

Yet, in There There, most of the book’s Native folks show up around a moment they struggle to change: upon feeling the feeling that comes shortly after seeing themselves in the mirror. Powwow newbie Orvil Red Feather feels too big to fit in his grandmother Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield’s old regalia, where he “…catches the hesitation and worry in his eyes, there in the mirror,” perhaps influenced by Opal herself, who “had been openly against any of them doing anything Indian” (118). Opal, a mail courier who finds relief from historical futility through reading and counting the even and odd numbers of the suburban concrete, sees it too:

“Every time she gets into her mail truck Opal does the same thing. She looks into the rearview and finds her gaze looking back at her through the years.” (160).

Edwin Black, a comparative literature graduate whose mind and colon are colonized by day old pizza, Pepsi, and internet addiction, reacts to the mirror in the screen of his dead computer:

“[I see] my face reflected in it, staring first in horror at the computer dying, then at my face reacting to see my face reacting to the computer dying.” (63).

Black’s reaction in particular suggests that when seekers begin to explore the webs of knowledge that reveal messed up, difficult origin stories, they inadvertently risk disengagement in the form of spiritual stasis, leaving themselves so aware of thinking that they feel too constipated to produce a presence in their bodies, to map out their own histories.

There There obsesses over dispatches of consciousness, where readers experience the magic of perspective, of Dromes, dances of death and States, ineffable categories that brave the abstract, offer us the sounds of the soul rapping, the brain wrapped up in new and exciting word bundles. Tommy Orange takes up the challenge to articulate the inarticulate, so the reader experiences plenty of well-placed “fucks” and “things,” the valuable ability to notice “something that looked like remembering and dreading at once” (33).

“Thomas Frank/The State” is perhaps Orange’s strongest standalone: it is full of passages marked by the author’s brilliant consecution and rhythm, snap crackles that pop from top to bottom. Beyond poetics of intergenerational, racialized violence, Orange’s book bounces with well-executed flashes, as in this section, for instance, when Frank, the titular character, recursively works through his origin story, passing by the moment his parents watched him groove inside the womb:

“…once you got big enough to make your mom feel you, she couldn’t deny it. You swam to the beat. When your dad brought out the kettledrum, you’d kick her in time with it, or in time with her heartbeat, or with one of the oldies mixtapes she’d made from records she loved and played endlessly in your Aerostar minivan” (209).

It is interesting to note the struggles some readers have had with the plethora of voices. A fair chunk of this talk about There There inevitably includes some difficulty with his tangling of registers, an expressed upset over Orange’s oral approach to the story, where a first read-through might leave a reader wondering who the heck this Maggie is or what’s with all those spider legs creeping in, the somewhat in medias res ending perspectives, some of which are still left tangled by the book’s end. To what end? Perhaps the premise of these frustrations comes from the shock of orality on a large audience yet again, as though twelve is too large a number of Native voices to hear in a mainstream book.

Because what the characters in There There seek to change is the initial colonial impression, one that invites the defeating thoughts of an “Indian Head” heavily influenced by North America’s hefty stock of mock ups and imprinted descriptions, as invoked in the book’s prologue. While much of the talk about Gertrude Stein’s qualm with the Oakland of her childhood (about there being no “there there”) can offer a wonderful entrance point into the book’s complicated timelines, the uncapitalized “there” throughout attempts to beacon us into the moment-to-moment of these characters’ urban Indigeneity. And what ends up changing them forever is the power of the powwow, of their community gathering once again, the “dance that comes from all the way back there. All the way over there,” to restore confidence (234). It is in this “there” and in There There that readers can find a Native’s counter against the harmful impressions from first contact, a resilience, a wonderful claim to the beautiful and complex present tense.

Cody Caetano is a Pinaymootang First Nation and Portuguese writer with work recently published in Bad Nudes, Echolocation, and elsewhere. He is currently enrolled in the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Toronto, and is at work on a nonfiction manuscript under the mentorship of Lee Maracle.