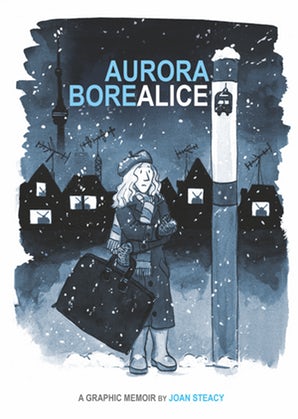

Aurora Borealice

Joan Steacy

Conundrum Press, 2019

Review by Kris Rothstein

Aurora Borealice, described as an “autobio/graphic novel”—a very light fictionalization of the author’s life—is the story of Alice, an irreverent underachiever from a working class family that runs a junkyard. It explores her relationship with creativity and the world of ideas, from her late teen years to middle age. We meet Alice as she announces her art school scholarship to the resounding indifference of her family. Despite this lack of encouragement or enthusiasm, and the obstacle of attending the local ‘dummies’ school, she makes it out of her small Ontario town. The effects of her stunted, appalling education will recur throughout her life, as she struggles with spelling, grammar and self-confidence amongst people who are well-read and intellectually sophisticated. Alice is tough and determined, and she constantly works to overcome embarrassment and the fear that people will assume she’s dumb.

Alice comes of age in the 1970s and the era is intensely evoked by the drawing style, the visual details and the particular anecdotes. Steacy is skilled at selecting snippets and vignettes that give a strong impression of Alice’s experiences and feelings. At art school Alice meets Ken, the funny and supportive man who will become a professional comics artist and her husband. He is also a friend of the McLuhan family (Marshall McLuhan was the influential pioneer of media studies who studied how media influences the way we think) and through him Alice meets Eric McLuhan, Marshall’s son, who becomes a friend, mentor and teacher. Alice later becomes a sculptor, but she does not make a serious foray into illustration or writing until she produces the memoir that is Aurora Borealice.

The story clips along at a fairly fast pace, with a focus on big life events: Alice and Ken marry, have kids, and move from Ontario to BC. Life just kind of happens to the couple, who enjoy an exuberant but low-key and undramatic relationship. They share a happy life in which they support each other, but this is not a story about love or marriage. And while it could be called a story of struggle, as Alice claws her way towards self-education and intellectual life, there is little professional or financial difficulty. Alice and Ken seem to have a winning combination of luck and talent. By the end of the book, Alice has achieved clarity and understanding, and has overcome many setbacks to become an instructor, artist and author. Steacy acknowledges that this is a novel in name only— that the character is her and that the events all spring from her life.

Ideas inspired by Marshall McLuhan run through the book—how the acts of writing, thinking and creating change us and those around us, and how form and environment affect our perception. Alice grapples with how we tell stories and put them together, which is something she doesn’t believe herself capable of at first. In one class, her proposal is chosen for a billboard project—the words, pictures and content of the project have no message, instead leaving the interpretation open to each viewer. Alice’s intention is to explore and have fun with the doctrine that the medium is the message.

The aesthetic of Aurora Borealice is a combination of cartoon and illustration. The art is printed in beautiful black and white—with rich, intense grays, which add atmosphere, depth and warmth. The gradations in tone are sophisticated, though the images themselves are somewhat naive and deceptively simple. Steacy uses the form to play with perspective (e.g. aerial views) and to use visual fantasy to explain ideas (Alice and Marshall McLuhan become fish to explain the idea of submergence within a culture). Alice has a big, open mind and her playful imagination is rendered and expressed in the aesthetic of the book. Steacy never allows this playfulness to interfere with storytelling, though, usually keeping it simple with regular squares as well as elegant, long rectangular panels. The lines are clean and simple, but the scenes burst with life, including many dogs, cats and other animals.

There are a few weaknesses in the book, mainly that it can get repetitive—cutting some scenes would have made the narrative more focused and concise. Steacy also has a slight tendency to over-explain. Much of the dialogue is didactic, and not totally believable as natural dialogue between a husband and wife. Alice often repeats her dismay at the way she was treated by the educational system to Ken, and after decades together it seems as if this territory would have been covered. In what may be an ironic or joking reference to the amount of exposition in the book, Ken says, “Yeah, I hate exposition too—that’s why I read comics. The visuals are all there, so no need for description, and the word balloons contain all the dialogue.” There are a lot of conversations about how and why we educate ourselves, and how we learn to interact with ideas and our environment. But there is also a lot of playful visual context, which balances the text. Alice suggests that combining media to create artworks like graphic novels is actually the best way to communicate ideas. This kind of storytelling uses words and images to engage multiple parts of the brain, and Steacy has used Alice’s theories to create a beautiful and effective literary reality.

Kris Rothstein is a literary agent, editor and cultural critic in Vancouver, BC. She writes regularly for Geist Magazine and can be found blogging about film, comedy and books at geist.com/blogs/kris.