Questions by Cara Nelissen

What follows below is an interview with the author Paul Zits, in which he talks the writing process and inspiration for his latest book Exhibit (University of Calgary Press, 2019), as well a poem from the collection.

Exhibit centers around the 1926 murder trial of Margaret McPhail, who was accused of murdering her brother. What was it that drew you to this subject in the first place?

I had discovered details of the trial, initially, from a handful of pages retained by the lawyer who represented Margaret in 1926. These pages—held in the archives at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary— constitute the majority of Margaret’s testimony, but represent, of course, only a small portion of the full transcript. I was drawn in, quite simply, by her responses to the prosecutor’s questions. The details that emerged were quite strange, and allowed for a truly complicated story to unfold. Margaret is tasked with having to explain some very strange choices she made over the evening of his death. For one, she claims to have thought that the bullet-hole to his head was, in fact, an abscess, which she spent some time in cleaning. While unresponsive, she also fed him wine, prying open his mouth with a spoon and pouring it down his throat (the constable who attended the scene found the spoon still lodged between his teeth upon his arrival). While Margaret offers the suggestion of suicide, it becomes difficult to reconcile this when one considers the two bullet wounds, the fact that he was discovered partially nude, and that he was found to have recently ejaculated. I wrote a handful of pieces based on the contents of this fragment, but eventually abandoned the project. It wasn’t until I discovered her mugshot that I became sufficiently inspired to search for the full trial transcript and police file.

Poetry is an interesting form for exploring a murder trial, which tends to focus on truth and fact-finding. Do you think there’s something about poetry as a form that enabled you to explore this subject matter in a way that other forms might not?

I don’t know that poetry is the superior conduit, in terms of form. A poet is more concerned, I think, with image and sound, so the experience is different, the material more evocative. I wanted to disturb the reading experience, which is something that I explored quite fully in my last book, Leap-seconds. Because I believe poetry allows for form and content to be better integrated, I think that the reader becomes engaged in a way that is different were the same subject matter to be treated more narratively. The trial itself is a process of narrativization, a way to organize and make sense of details and facts. By poeticizing them, details and facts are experienced very uniquely. They are animated a little differently, less cemented.

While Exhibit is centered around the murder trial, the reader never finds out if Margaret was found guilty. Was that a conscious decision? How do you think focussing on the trial rather than the outcome shapes what the book is speaking to?

The decision to write the book without any knowledge of the outcome was absolutely deliberate. I wanted to avoid the pull that this understanding would have had on me, and the impact it would have had on the shaping of the book. I wanted to allow my impressions of the case to vacillate, to avoid as much bias as possible, and to capture these waverings. I wanted the freedom to absorb new data, new testimony and evidence, with an open mind. It also allowed for my characterizations of both Margaret and Alex to remain fluid. I feel as though any foreknowledge would have coloured my suspicions and might have significantly narrowed my readings of the case. By repudiating either narrative as over-simplifications, I found myself more open to the nuances of the case. The book became more about relationships, desire, mental health, and trauma. To this day I remain completely unaware of the outcome.

The book is structured into sections titled Exhibit A through E. How did you go about structuring the book?

The structuring reflects, more or less, changes in form, which in turn reflect changes in perspective. At times it felt necessary to explore Alex’s psychology, and this called for a sequence of poems that look very different from those exploring Margaret’s experience. Some pieces, and some sequences, are written from Margaret’s point-of-view, while others are written from a variety of third-person perspectives. The sections, or the way the book is sectioned into “exhibits,” also asks one to consider how collections—exhibitions with either aesthetic or historical focuses—shape meaning, influence beliefs, configure collective values, and give structure to social understandings.

This is a collection of collage poetry. Could you speak a bit to how you worked with the source material to write your poems?

The poems are sourced from relatively stark statements made during the trial, so my intention was to elevate its language with contemporary source-texts, rendering key moments, key revelations, more complex and provocative. Endeavouring for the work to take on a strong surreal quality, and employing a variety of cut-up techniques and collage-work, folded into these poems are cuts from a broad variety of sources, including interviews with Catharine Robbe-Grillet and Eileen Myles, English and Russian fairy tales, and articles on the history of feminist film, to name but a few. I wanted the work to have clear referents to the world we know today, so that the case, although nearly one hundred years old, had an immediacy to it. A quote by Karl One Knausgaard, from A Time for Everything, which became the epigraph to the book, and which I reproduce below in its entirety, became a major driver for the aesthetic choices I made throughout the writing of the book:

“And as each new age is convinced that it constitutes what is normal, that it represents the true condition of things, the people of the new age soon began to imagine the people of the previous one as an exact replica of themselves, in exactly the same setting.”

What are you working on right now?

I am currently at work on two new poetry collections. One is a pre-apocalyptic narrative that follows a mother-figure and daughter-figure through a series of deteriorated prairie landscapes, in search of whatever form of preservation they might find. The second is about masculinity, and traces its features from those that are ostensibly benign, to those that constitute its most toxic forms.

Warm summer afternoon underclothes

Ladies ice-skate on this man’s bucolic.

They woodcutter his lifelong equestrian fantasy.

Ponds frame the vast gardens of their château.

Madame occasionally picnics in the man’s mouth

in a little white-and-green rowboat.

She pulls back the nature of their intimacy.

He gives himself to her body and ejects. She does

whatever she wants, has to get it out some whenever she wants.

She would then reload.

Roar with a twenty caliber single shot laughter.

While he wonders just what rifle?

What ejector?

Margaret otherwise is in good order.

It is my secret garden, she says.

The door opens inwards.

Her head is in backstage preparations.

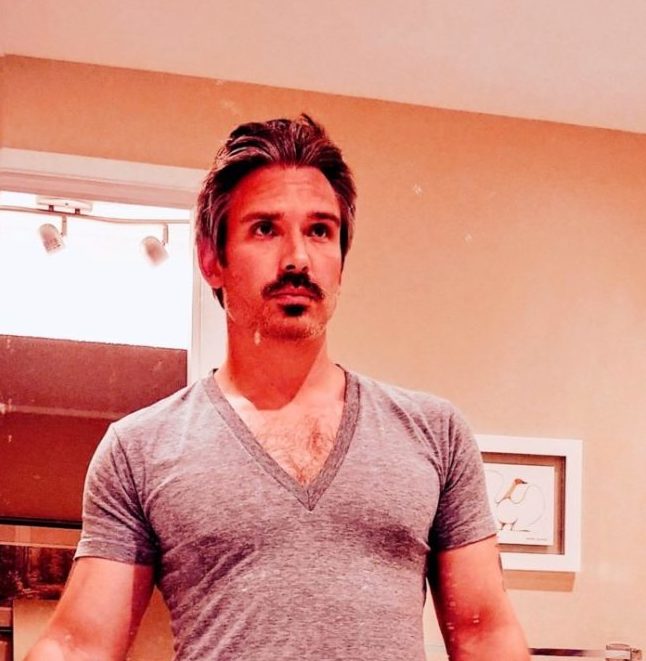

Paul Zits received his MA in English from the University of Calgary in 2010. His first book, Massacre Street (University of Alberta Press, 2014), won the Stephan G. Stephansson Award for Poetry at the 2014 Alberta Literary Awards. His second book, Leap-seconds (Insomniac Press, 2017), won the 2016 Robert Kroetsch Award for Innovative Poetry. His latest collection, Exhibit, was published earlier this year by the University of Calgary Press. Zits is currently a teacher with the Calgary Board of Education.