By Jess Taylor

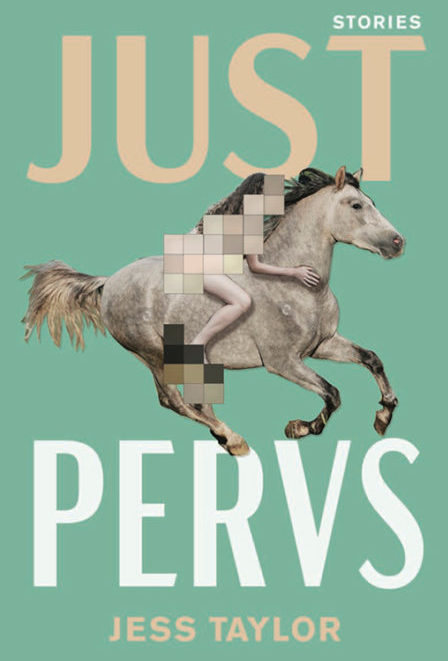

This story is an excerpt from Jess Taylor’s new collection “Just Pervs”, which is now available from Book*hug Press

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night, from one bad dream or another. I get up, eat a banana, drink a glass of water, maybe make a cup of peppermint tea. I play so many pieces of my life back like snippets—remember confessing to my best friend, Sam, that I felt as though I wanted to die and that she was the only one I could tell at that time. The lowest point in my life plays over in my head, so many bad relationships and unrequited loves, when after enough time it became clear that it was all me: I was the one drinking too much and throwing fits, hurting people’s feelings and acting the fool, all because I hoped to be found interesting.

Alone in my apartment, I find this pathetic. I know, in theory, that I should treat my past self with compassion, recognize her for being the young person she was, but god, I hate her.

That’s when I think of calling Sam. I’ll tell her I need her, that I’ve never had a friend like her, and ask her why she’s drifted from me. Then I realize that this overdramatization of a very simple thing—missing an intense friendship—is exactly what always went wrong, that I am tired and more prone to worrying in the middle of the night, that I’m not myself, and should put myself back to sleep.

I was twenty-three and Sam was twenty-four. Or maybe I was twenty-four and Sam was twenty-five. Either way, we didn’t have the fear yet, and we lived each day that summer as if we’d never die. Not that many bad things had happened to us yet, I hadn’t quit drinking, and everything was exciting. We were going to take a cab down to the harbour at Yonge and Front and go on a daytime cruise. Sam was great at partying. She went to many boat parties, but usually they lasted a whole night, until the morning was coming, and then kept going even longer. The ones during the middle of the day were for people who weren’t true partiers: bros and their girlfriends, people who partied for pictures on social media. But Sam’s friend’s boyfriend was DJing and she was loyal and wanted to support him. We also wanted to drink.

The only catch was that this party had the theme of Tight ’n’ Bright. Which basically meant you needed to wear something that was tight and bright. I’d picked out a magenta lace tube dress, which was too formal, too hot, too dark, but at the time I thought it made me exceptionally attractive. It did not. But Sam swore I looked great, as she tried to decide what to wear herself. She finally pulled on a bright tank top and black skirt. Her belt was thick and black and her eye makeup was almost goth. “Fuck Tight ’n’ Bright,” she said. “No boat is telling me what to wear.”

As the cab approached the boat, we saw herds of bros in pink and yellow neon tanks, girls walking in neon swimwear and crop tops, bright white shorts and skirts. As soon as we got on, people threw Mardi Gras beads over our necks in blue and purple and gold. The whole boat looked as if some little kid had eaten a box of crayons and then either shit or puked it out. I was disgusted with myself for being there, but then Sam put her arm around my waist and gave me a hug, saying, “Kylie, I love you.” I felt as if I’d give up every good thing in my life for a friend like Sam.

The sun was hot, and it probably was only just creeping up to 1:00 p.m., and I was soon drunk on Corona. I’d forgotten I hate boats. They rock and make you sick, and they only ever sell one type of beer. My mouth tasted like old bread and lime. The alcohol made me lonely, although I was dancing with Sam and her friend, right by where the boyfriend DJ’d.

I started looking for a love. A cameraman was videoing the whole thing for the production company that ran the boat. He was a type I often was into—skinny and troubled, out of place on the cruise, like me. I kept trying to goad him into having a real conversation, one that acknowledged that we both didn’t know how we’d ended up on a day cruise like this, that we didn’t actually know how we’d come to know the people we knew, that our thoughts were so much deeper than those of the people around us.

Despite all this, he didn’t really notice me. Girls were everywhere, all tighter and brighter than me. He filmed people he felt were interesting, and I followed him, dancing as close as I could without blocking him. He turned his camera to a man who was tall, shirtless, broad-chested, and grinning. That smile—I was in love already. He had the whitest smile I’d ever seen, the perfect shape, like all the movie stars have, a crescent moon fallen to rest on the face of a man. He was obviously a bro, not my usual type, and I had no desire to talk to him. I just wanted to have sex with him—then and there. I joined a group of girls who all seemed to know him and danced on the outskirts of the circle, hoping he’d notice me, the cameraman forgotten.

And he did notice me. He gave me the elevator and I thought he was checking out my tits, but then I realized he was checking out my dark magenta dress. “Hi,” I said with a huge smile, and took a swig from my beer bottle. “Sorry, this not tight or bright enough for you?”

“This is my brother,” he said, and gestured to a guy beside him. A kid, really. The brother had the same smile, but his face was fleshier. He was wearing a neon green tank top that looked as if it’d been washed with something brown. This was Tight ’n’ Bright. The boy from the lowest point of my life.

“How old are you anyway?” I asked.

“Twenty-one,” he said.

“Aw, that’s not that bad then.” He glared at me and told me I looked barely nineteen. I told him my actual age and then began to tell him about my adventure with Sam to the bathroom. We’d stumbled across a group of boys near the front of the boat when we were looking for the bathroom and some fresh air. They were all holding on to each other and howling into the sky, directly at the sun, “Coke! Coke! I need some coke! Do you know where I can find some coke?” One ran right up to me, giggling. “Know anyone on this damn boat with some coke, sweetheart?”

Back then, Sam only did drugs that made her dance, and wasn’t old and weary enough to need drugs to wake her up. By the time I was thirty, I understood why everyone tried the drugs they did, even though I never dabbled in anything other than weed. Drugs weren’t something that caused people to be evil or always originated from a self-destructive impulse, the way my binge drinking did. A lot of the time, people did drugs out of sheer self-preservation, trying to get through another night or find enjoyment in things. Then bad luck or genetics or lack of foresight got some people hooked. That was all.

At the time, though, I feared drugs and the people who did them, as if those people belonged to another world that teetered at the edge of mine and, if I let them, they would consume me. I knew I wanted to rip myself apart, and allowing access to anything that would make me go insane quicker than I already was going on my own was dangerous. So I told Tight ’n’ Bright, “I don’t like that stuff, do you?”

“Nah, I’m not into that,” he said. He seemed, momentarily, willing to connect with me. “My brother is, some of his friends, but I’m just not into it.” I wonder if that’s still true of Tight ’n’ Bright, or if it was just because he hadn’t grown up yet.

We stopped talking because it was getting us nowhere and began to dance to the music. He bought us more beers and I drank mine quickly. “You’re done already? I’m not buying you another,” he said.

“Do you have somewhere we can go after?”

“Yeah. We can go to my brother’s place,” he said.

Earlier that summer, Sam and her boyfriend broke up, so we hit up the LCBO. She grabbed a two-litre bottle of wine off the shelf. We got a small bottle of vodka and some juice for us to drink at her sublet. “What’s the wine for?” I asked. “Going to a party?”

“It’s for my depression,” she said. She was only half joking, I knew. Sam had moved into a sweltering sublet, a condo like a box, with no AC. She spent most of that summer drunk and sweating, which is what people tend to do, at least in Toronto, when they’re going through a breakup during the summer, when everyone expects you to be outside and happy, smiling into the sun like we-can’t-believe-winter’s-over. Of course Sam had to drink. She was always ready to meet up, so we could go on another adventure or just complain about our lives or run errands together.

At her place, we got so drunk I could barely walk. I think that was the night we went to a party for Pride, but I can’t remember. I found some shirtless guy and we made out while people danced around us. “Trust you to find some guy to make out with at Pride,” she said.

I laughed and shrugged. In my mind, almost everyone was bisexual anyway. I certainly was.

I fell asleep on Sam’s floor inside a duvet and woke up sweating with a pounding headache. She was right, the apartment did hold in the heat. I got up. “Sam,” I said. She didn’t move. I was too hungover to even know what to do. I needed to get home to my cool basement apartment, curl up, and fall asleep until my headache left me.

Her eyes sprung open. She turned and looked at me.

“Hi,” I said.

“Holy shit!” She jumped up and pulled her blanket around her, so that only her head poked out. “Kylie, I forgot you were even here.”

“I gotta go. My head. I can’t.”

She was back asleep within minutes. I walked home, even though it took about an hour. I couldn’t really afford a cab or even transit. Even in a heat wave, it was cooler outside than in her apartment. I wondered why I’d drunk so much, why I’d made out with that guy, why Sam was scared when she saw me in her apartment, who I really was. I began to cry as I walked home. I didn’t know if it was because of the pain in my head, my life, or what. Even though I was poor, I was luckier than most, I knew. I had an education, I had Sam, I had a family I could call on the phone and confide in. Maybe that’s when the hate in me started to grow. But I’ve told you before, it’s always been there, always.

Tight ’n’ Bright grabbed my hand, and we walked away from the harbour and across the parking lot. Someone was puking beside a car, while their friends filmed it on a smart phone. All of the pink-neon-clad cruisegoers found their cars or walked up toward the street to take cabs home. None of the boat people took streetcars. I’m sure they felt like public transit was beneath them. They were just that kind of people—not like me and Sam. By this point, I’d lost Sam and sent her a text to tell her where I was going. I knew she’d come looking for me if I disappeared or ended up dead.

“Are we going to get more booze?” I asked him. “I don’t have anything to drink.”

He flashed me a credit card that his brother had given him, pointed out an LCBO. He tugged my hand, dragging me toward the store. Inside, I let go of him, weaved in and out of the aisles. I still felt like I had as a kid, going in there with my parents, asking questions about the different-coloured bottles, trying to get my mom to buy ones that had pictures on them. Pretending I was of age, standing in line with six bottles of wine while my mother ran to get one she’d forgotten. I had one of those moments with Tight ’n’ Bright too, where I worried that I’d lost him like a kid loses a parent in a supermarket, that I’d be left in the store until some other adult chose to bring me home. I found him with a small bottle of vodka in his hand.

“This is for my brother,” he said.

“That’s not enough for all of us,” I said. I grabbed two tallboys from a display. “Can you buy me these?”

“No.”

“No?”

“It’s my brother’s card. I’m not buying you shit.”

“I thought you liked me.”

“You’ll have to buy your own.”

We waited side by side in line. I used my credit card to buy the two tallboys. I was furious. I’m not sure why I felt he should buy my beer for me. I was worried about money all the time, and I guess I thought that if he wanted me to stay out and go to his brother’s with him, at least he’d buy me a drink.

We argued all the way to his brother’s lakeshore condo. The sun was finally starting to set behind a row of skyscrapers, the light sharp and violent in its reflections off the glass corners. Going up into those buildings would have been impossible to me, even just a few hours ago. No one there wanted me.

Sam moved up north with her first husband when we were in our late twenties, and we lost touch for a bit. At the beginning, I’d call her. She’d say, “Thank fuck you called—I’ve been going crazy here all by myself with just Travis.” He liked to hunt, would go on trips for days at a time. It seemed as if mostly she just did drugs. She had a job teaching at a school just outside a reserve. Sometimes she’d cry to me about all the problems the kids had—she cared so much and was broken when she couldn’t do anything to help. My phone would go off in the middle of the night and it would be Sam, ranting about her life, how cold it was up there in winter, how she thought Travis was fucking around. She had a knack for always calling while I was masturbating. Sometimes I’d finish and call her back; other times, I just wiped my hand and answered her call, slightly out of breath. She never noticed.

I quit drinking because it was making my life horrible. It wasn’t that I had a problem—at least that’s what I told myself. I just was sick of feeling like a shit-show. I found that after I quit drinking, it was easier to hold the rest of my life together. Easier to realize I had very few close friends and that was something I could change. I saw a therapist and we used phrases like “incremental change” and “positive action.” I was beginning to live a life that didn’t make me want to kill myself. Tight ’n’ Bright began to seem like one episode in a life that would be long, peaceful, and happy. The me who’d experienced Tight ’n’ Bright still existed, but she was tired and pleased with herself for making decisions more slowly and for finding time to be alone. For realizing that true love wasn’t found in a bar or on a boat. I still didn’t know where true love was, but I felt more confident that it existed and that I’d find something good for me one day.

At Tight ’n’ Bright’s brother’s condo, I tried talking to people, but they turned to each other instead as I sipped one whole tallboy down and then the other. Everyone talked about drugs, getting fucked up. How much drugs cost and the way they made them feel, how much they had and how long they’d last. I whispered to Tight ’n’ Bright, “I told you I don’t like that stuff.”

He said, “Come on,” and led me away from these people who didn’t like me. It was the only nice thing Tight ’n’ Bright ever did for me.

We went into the bathroom. We began to make out sloppily, like teens first learning. I pointed at the shower. “I like water,” I said to him. “It makes me horny.” He ran the water in the shower and we piled into the bathtub for a second or two with our clothes on, me on top, making out with water streaming down our faces, and then he had his dick out, the skin all soft and wrinkly, and I pulled my panties off and we had sex for a minute without him fully hard before I remembered I wasn’t on the pill and we’d better be careful if I didn’t want to have Tight ’n’ Bright’s kid. “Listen, we need a condom,” I said, or I just got sick of just rubbing against his semi-hard dick in the bathtub, so he took me to his brother’s bedroom.

He kept trying to have sex without a condom, and I kept stopping him, saying, “I’m not on the pill y’know!” with a tone of voice designed to inspire shame. He rooted around underneath his brother’s bed. The bed was a king and the bedding was in layers, like you’d see in a hotel—first soft red sheets and then a grey duvet. Pillows in red pillowcases for sleeping and grey pillows for decoration. I thought about his brother’s perfect smile, the same smile as Tight ’n’ Bright’s, but in a better face. Like the room, the box Tight ’n’ Bright finally found was made of pristine polished wood. Inside was a folded-up set of condoms.

I couldn’t imagine someone lived like Tight ’n’ Bright’s brother did. It didn’t make sense to me. Although I wasn’t that much younger than Tight ’n’ Bright’s brother, I lived in a basement apartment with very little light. I had a double bed that I’d bought when I was eighteen, when I first moved out of my parents’ house. Sometimes when I was too lazy to walk to the laundromat, I left the stained mattress bare and slept on it like that. I had long ago broken my bedside table lamp, so it didn’t have a shade. I’d tried to duct-tape a shade in place for a while, and some duct tape was still on the lamp, right where you screwed in the light bulb. One night, I’d spilled a glass of water all over the floor and over my lamp and power bar and then touched the water and electrocuted myself. I called my parents crying in the middle of night, worrying that perhaps I would die of delayed heart failure from being electrocuted. I didn’t even have a burn.

We kept trying to get a condom on Tight ’n’ Bright, but it kept slipping off. He didn’t even seem all that concerned with actually getting his dick in me. Instead he started to fingerbang me. It was as brutal as you might imagine. He jammed his fingers in straight, obviously not knowing anything about where the G-spot was (and to be honest, at that time, I didn’t really know where it was either), and rammed his fingers in and out faster and faster until I was screaming, “Stop! Stop!” I finally bent my leg up and used my foot to push on his arm at the elbow, pulling his fingers down and away from me. I rolled over onto my stomach.

This would have been a good point to just go home, but something got into me back in those days. It was like no matter how embarrassing the situation was, if we just had sex, it would all be better. I’d feel great, for a moment at least, and not even physically. Psychologically. I especially wanted the feeling of someone’s body pressing on me. But I didn’t know that at the time.

“Are we ever going to have sex?” I said to Tight ’n’ Bright. “Where the hell are the condoms?” He smiled at me and tried to put his fingers into me again. “Stop, do you even know what you’re doing?” I said.

“I’m a virgin.”

“Really? It’s your first time? Look, if it’s your first time, you don’t want it to be like this, you want it to be with someone special.” I rolled onto my back and stared at the ceiling. “I was eighteen when I lost it. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to before, it just was never right… My boyfriend in high school didn’t think we loved each other enough, that I didn’t love him, and he thought it was important for me to have sex with someone I loved. I guess it was. But I didn’t know I didn’t love him, you know, until he told me, I just wanted to have sex so bad. But then I met Jonathan, who I dated for four and a half years before I moved to this hellhole, I mean before I moved to Toronto—well, you know what I mean. And we really loved each other, for a while at least. He loved me. And I was so glad I waited, even though it took longer than I’d wanted.” Part of me thought about how this scene would look from the outside—that I was so old and wise compared to this boy, experiencing his first time with a woman, not knowing what to do. I’d been wrong to treat his ignorance with frustration, even cruelty. He needed tenderness in this moment.

“You actually think I’m a virgin?” he said.

I didn’t know what to believe. We found a condom and had half-hearted sex. It remains some of the worst sex I’ve ever had.

When we came out of the room, the place was deserted. It wasn’t even midnight. “I’ve gotta go,” I said, and kissed him bye and beat it. I went to the elevator, calling Sam on the way. She picked me up in a cab.

“Where the hell have you been?” She handed me my backpack. She was going over to a friend’s place with air conditioning and was determined to eat a whole pizza herself.

“Can I have a little?” I asked.

“You can buy a piece,” she said.

“I’ll wait till I’m home.” At home, all I had were a few sad potatoes keeping each other company on an empty fridge shelf. We both knew it. She bought me a slice and the cab took me home. I thought I’d wake up in the morning and, other than my hangover and a vague bad feeling, it’d be like Tight ’n’ Bright never happened.

Around the time Sam’s marriage fell apart, I stopped drinking for real. Not just levelling off, not just switching from beer to vodka soda, not just a few drinks when I was out. Nothing. At first, she thought this was pretty great. “I’ve given up on love, and you’re giving up on drinking, perfect,” she said. “I should drink less too.” She’d already said she was going to stop doing drugs now that she wasn’t with Travis anymore, but drinking was something different with her. It wasn’t an all-or-nothing thing like I’d always experienced it—I kept quitting and starting, making rules and breaking my own rules. I wasn’t an alcoholic, I reasoned, I was just concerned, overly nervous. Both my parents were alcoholics and were usually drunk if I called past 8:00 p.m. I wanted a life that was different. For Sam, drinking was like a quiet thrum in the background, sometimes louder and quieter, but always there.

It wasn’t long before she stopped calling me. Sometimes we’d still hang out, but it was always in the daytime, when I wouldn’t be tempted to drink. I made new friends, I became an active person, sometimes it felt as if I had a totally new personality, especially if I compared myself to the person who’d been with Tight ’n’ Bright, but then I’d remember myself as a child, sitting on a hill, feeling the sun, pulling blades of grass from the ground, writing or singing to myself little songs I’d made up. Happiest alone.

When I woke up, I had Tight ’n’ Bright’s number in my phone and I was missing my sunglasses and my watch. I instantly knew I’d forgotten them at his brother’s place. Lots of people forgot stuff, he texted me back. Message my brother, I’m sure he’ll help you. He gave me his brother’s number and then we never spoke again.

I went back to the condo by the lake. Found enough coins to take the subway both ways and rode south for about an hour, thinking about what I’d be walking into. What did his brother think of me—locking myself first in the bathroom and then in the bedroom with his younger brother? Using all the condoms from his stash. Forgetting my belongings somewhere deep in the recesses of the apartment.

I didn’t find any sunglasses, his brother had texted me. I was surprised that he used full sentences, apostrophes. My friend had his wallet stolen too. The sunglasses had been expensive, a gift from my mother, and I’d managed not to lose them for two years. One boat cruise later and they were gone. I have your watch though.

As I rode the elevator up to his place, I worried. That he would kill me, rape me, that I would be found all over the city in pieces, that I would never see Sam or my parents again, that I’d finally made the mistake that meant I’d be gone for good. I also thought about the flipside—what if I got there, and he saw me, and he fell in love with me? He would invite me to live in the condo, and although, on principle, I didn’t like condos, I would like living with him very much. In my fantasy, he never wore a shirt and we never left the apartment.

I glanced at myself in the mirrored walls of the elevator and was faced with my own shabbiness. I was not unattractive, but I definitely was a slob, and things like the heat or the rain made me look wild. I also didn’t know how to make any of my clothes look as if they belonged together or as if they would even be picked out by the same person. For instance, I was wearing a crummy dress and New Balance runners that were beginning to wear through. I believed looking put together meant that you bought into capitalism, were shallow, and had no soul. But for a moment, before knocking on the brother’s door, I regretted these beliefs.

He invited me in, and I stood in the hallway of his apartment beside a set of golf clubs. “One second,” he said the instant he opened the door. He smiled the crescent moon but didn’t make eye contact with me.

He walked over to his kitchen counter, grabbed the watch from his grey granite countertop. The band was fraying. If I’d been a different person, it wouldn’t even have been worth going back for. I took the watch from him, thanked him. He said it was no problem but looked annoyed. One more ride down the elevator and that would be it, I thought. Enough of Tight ’n’ Bright. Enough of these trailing results of Tight ’n’ Bright.

I’d like to be able to tell you I learned something from Tight ’n’ Bright, from the lowest point in my life, but I can’t really say I did. I also don’t really know why I considered Tight ’n’ Bright the lowest point, when really so many others were still to come. I guess Tight ’n’ Bright made me feel humiliated—a piece of shit destined for other pieces of shit—committed to living a life that made me terrified for myself. I knew what I was doing, I knew I needed to lean away from it, but had chosen to lean in. I was aware of myself and my decisions. Perhaps Tight ’n’ Bright was really that moment, the moment I awakened to what I was doing. Or maybe that was when I realized I had to lean in to learn how to lean away—or there were no realizations, only seconds in a life without purpose.

I had cramps, but my period didn’t come. My boobs swelled and hurt. I pressed them at night in the dark. The ache felt good and bad all at once. I put a finger inside myself every time I went to the bathroom, hoping to see the faintest trace of blood, but, like on the toilet paper and my panties, there was nothing. After two weeks, I was freaking out. “It couldn’t be, right?” I said to Sam over the phone. “I mean, we only really had sex for like a second and that was with a condom on.”

“I don’t know, girl. Did you ever have sex without a condom?”

“No, of course not.”

“Are you sure?” I was annoyed with Sam for making me come face to face with myself at the time. I often became frustrated with condoms, was too eager for sex, too eager for skin on skin, and just risked it. I’d say things like just for a second and just don’t come in me and I’m not on birth control, this is crazy.

“For a minute, in the tub.”

“Kylie!”

“What?”

“Well, you might be pregnant. And might have an STD too.”

“Whatever. I can’t be, right? I mean, he was barely hard.” This was before I got my IUD and my period was always irregular anyway. I walked around the city with Sam, prepped for tutoring in cafés with Sam, ran errands with Sam, all while thinking, Maybe Tight ’n’ Bright’s baby is in me. Imagine if he had been a virgin and knocked me up on his very first time. Stupider things have happened, but not by much.

I think a very specific difference may be the thing that makes people want to kill themselves. Or maybe it was just the very specific thing that made me want to kill myself. It’s the difference between who you are and who you act like and who you want to be. When who you are is the same as who you want to be, who you feel you should be, you feel happy. When who you are is different from who you want to be, you are discontent, frustrated, maybe even depressed. But when who you are is different from how you act, this is when you want to kill yourself. Especially when how you act is as far away as possible from who you want to be.

I met people through yoga and climbing and a running group I joined. I learned how to breathe with other people. I explored my many interests. I worked hard and set up my apartment in a way I liked. One time when Sam came over for coffee, shortly after she met her new boyfriend, Brad, she told me I was different now. “With all your Basic White Bitch healing. Is that all you think about all day?” She named several things that could better serve my attention. The world was in political turmoil. Racist extremism was getting more open each day. She’d seen injustices that were part of children’s day-to-day lives. She’d also heard Travis had gone into the hospital, maybe for an overdose, but she never talked to him anymore and talked about her feelings about him and the drugs and the time they’d been married even less. I figured Sam was being typical Sam, that all of this would eventually come to a blowout, that she’d accuse me of being boring or abandoning her. But I was always the one worried about abandonment, not her. And really she was right, the old me who was poor all the time and resistant to spending money at all would have been shocked by the me now constantly spending money on myself, feeding the capitalist machine.

It’s not that Sam and I aren’t friends anymore—just that she’s someone who’d very vividly been in my life, only to slowly fade away, like so many others.

Sam and I walked to a Shoppers one day. As we stood in the Family Planning section, I resisted the urge to buy condoms. It’d seem dumb with a pregnancy test and I already had an unopened box at home, but I thought it’d be so funny. I thought about the face the cashier would make and started laughing. I told Sam about the scene that was in my head, and she rolled her eyes and shoved me slightly into the shelves of boxes and boxes of condoms, red, blue, purple, and yellow. A tube of lube toppled over and I laughed harder. Fucking Tight ’n’ Bright. Tight ’n’ Bright, of all people.

“Here,” Sam said. “The tests are over here.” She stood looking at the pregnancy tests, trying to decide which one would be best for me: Clear Blue, First Response, AccuClear, Result, or the regular old store brand, which was on sale. I’d gotten paid for tutoring that morning, had a whole sixty bucks in my wallet. I was ready to go wild.

I picked up the First Response pack of two. “This is a really good value,” I said to Sam. “Two tests for the price of one!” I started laughing again. Sam smiled, but looked sad. Two of her other friends had had abortions within the past three years and I’d forgotten, the way I did with everything. I only remembered later, when I was alone in bed and thinking about how she hadn’t seemed herself. Wondered if I’d done something insensitive again.

Sam came with me to my place, and I peed on the test and we waited. She grabbed the test from me and poured us both vodka and juice. “So,” she said. “What do you think it’s going to be?”

“Just let me see it.”

“No,” she said, and drank. She poured herself another drink and drank again, holding the test in her hand, waving it in the air. “I want you to think about what you’ve done.”