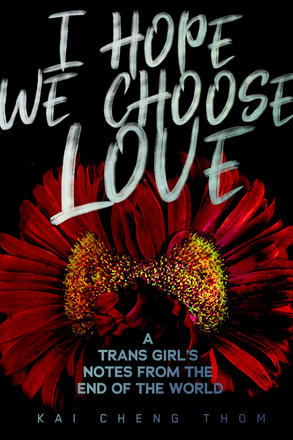

I Hope We Choose Love: A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World

Kai Cheng Thom

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

Review by Jaz Papadopoulos

When I first heard the phrase “A Trans Girl’s Notes From the End of the World”, the subtitle of Kai Cheng Thom’s new book I Hope We Choose Love (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019), I thought I was receiving oracle from the future. However, it would be mistaken to think Kai Cheng Thom’s newest book of essays and poems was written for any time besides the right now.

In this collection that bridges poetry, list-making, cultural criticism, queer archaeology, and personal essay, Thom tackles the shadowy underbelly of today’s social justice movements with urgency and, more importantly, a stunning amount of care. The title, I Hope We Choose Love, may sound fluffy––especially for disillusioned retired punks like myself––but Thom is steadfast. “We live in poison,” she writes. “The planet is dying. We can choose to consume each other, or we can choose love. Even in the midst of despair, there is always a choice. I hope we choose love.”

The thread that most struck me throughout this book was “goodness.” Thom empathizes with the way queers, trans folks, and other marginalized people seek acceptance––confirmation that we are good. We’ve inherently failed our parents’ idea of goodness. We’ve inherently failed society’s idea of goodness. But, in the social justice-oriented radical queer community, we’ve created our own set of norms and ideas around what makes a good person.

Yet, these norms come with their own price. In the not-so-fictional world that Thom titles Queerlandia, “privilege is our original sin, and the doctrine is our Hail Mary.” To earn one’s place in this community, one must be good, or rather, appear good. But, what does that mean for a community frozen in a collective trauma response, where abuse, survival, suicide, disposability culture, and celebrityism fill the gaps between us?

In an effort to preserve the ultimate Safe Space protocol of Queerlandia, any sign of external imperfect behaviour is hunted, called out, and punished. “For Queerlandia is a dream of perfection, which means that only perfect people––perfect victims, perfect survivors––can live there,” she writes.

Thom makes clear that this process of disavowal does not in fact heal or prevent harm: it replicates the prison industrial complex’s thirst for punishment. Thom is not afraid to complicate an understanding of justice. (Or, maybe she is, but she is also courageous in her honest excavation.) In one of many potentially contentious statements, Thom writes, “I’m not a believer in justice because I have never gotten it from or against those who have harmed me.”

But, for every idea she tears down, Thom offers several new ones to take its place. For example, she draws express distinctions between punishment, justice, and healing. Healing, she suggests, is an individual journey. It is not related to punishment of another.

Thom exposes disposability culture as an amalgamation of call out culture, a consent culture that is overreaching to the point of being deadly, and the drive to be the perfect victim/community member. She marks neoliberalism as the force behind celebrity culture—wherein celebrities are rendered static, unable to grow and learn: they gain social capital points while losing the ability to make mistakes or to act with honour. She observes the way that “accountability” has come to mean “the ability and willingness to follow a script for the proper way to apologize”––a map for saving face, not reconciliation or growth.

Though these topics might be considered controversial, or at the very least, against popular opinion, Thom writes from the heart. She is not prescriptive or dogmatic, but rather writes as if speaking to an old friend whom she loves and truly wishes the best.

Admirably, Thom tells us within the book itself how she wants the reader to consider the book. Storytellers are not inherently healers, she insists, reflecting on her own experiences as a queer trans literary celebrity. She resists celebrity culture by writing honestly about how it has harmed her, and by presenting obviously unpopular opinions which push against binary modes of thinking and philosophy. Coming from a place of love rather than dogma is complex—there is no room for binary in the mess that is love and healing.

While reading I Hope We Choose Love, I couldn’t help but think of Mary Oliver’s words in her poem “Wild Geese.” “You do not have to be good / You do not have to walk on your knees / for a hundred miles through the desert repenting. / You only have to let the soft animal of your body / love what it loves. / Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.”

We do not need to be good. We do not need to be good for our parents, bosses, friends, or SJW community hot shots. We do not have to be good, because to do so would be to trade authenticity, growth, and kinship for a false label. The obsession with goodness, with abuser/victim binary, and the conflation of punishment as justice as healing, creates a binary where it is impossible to simultaneously be one’s honest, flawed self, and also be welcomed into community.

The benefit of writing from the end of the world is, where we so easily presume there is nothing to hope for, Thom reminds us that when everything changes, there is everything to hope for.

“[W]e will have to give up our defenses, our time-worn defences of dissociation and numbness, as well as those of rage and revenge,” she writes of our collective way forward. “We have to be able to care, even when it seems impossible because caring would destroy us. We have to believe that we will survive each other, that we will survive because of each other, because there is something waiting for us when the ice melts.”

Jaz Papadopoulos is an interdisciplinary artist working in experimental writing, installation, and video. They are interested in diaspora, bodies, place, memory, grief and ritual. A graduate of the Cartae Open school, Jaz is also a 2018 Lambda Literary fellow, and a current MFA student at the University of British Columbia. Jaz grew up on Treaty 1 territory and currently lives on unceded Coast Salish land. Follow them online at @scrybabybaby and vimeo.com/jazpapadopoulos