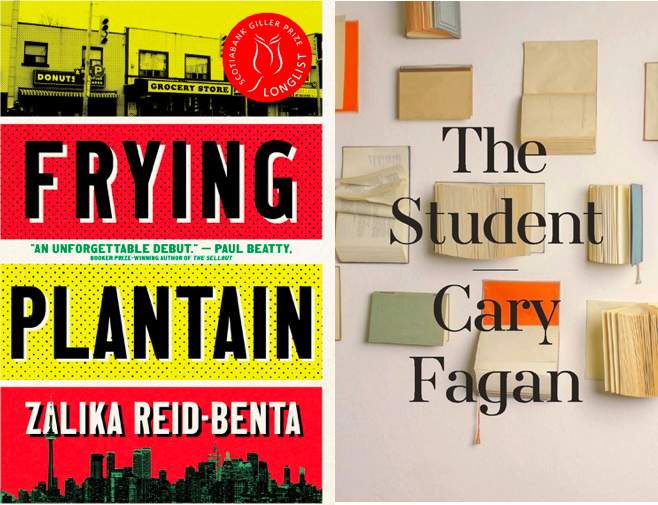

Frying Plantain

Zalika Reid-Benta

Houe of Anansi Press, 2019

The Student

Cary Fagan

Freehand Books, 2019

Review by Marcie McCauley

Right now, the construction of the Eglinton Crosstown LRT in Toronto is relentless: traffic is crawling. On the page, however, Eglinton Avenue is on the move: two recently published books feature fictional narrators travelling this real-life artery.

Debut author Zalika Reid-Benta’s linked-story collection Frying Plantain (House of Anansi Press, 2019) and established author Cary Fagan’s latest novel The Student (Freehand Books, 2019) both present young women whose lives unfold in midtown Toronto, one west and one east of the Allen Expressway. The young women’s experiences differ between neighbourhoods (Little Jamaica and Forest Hill) and time periods (one begins in 1957, the other in this century), but what these women share is a struggle to define themselves on their own terms.

A major east-west thoroughfare in Toronto, Eglinton Avenue is the only street to pass through all six of the former boroughs of Metropolitan Toronto. In both books, the protagonists travel in and around Eglinton. Their stories are rooted in quotidian urban detail—readers know where Kara likes to eat patties and where Miriam likes to buy books.While these locations secure characterization, the stories’ themes stretch beyond their borders.

Kara Davis, in Frying Plantain, grows up a couple blocks north of Eglinton on Whitmore and Belgravia, attends school a couple blocks south, frequents the convenience store at the corner of Eg and Locksley, eats at Randy’s Take-Out near Oakwood, and applies to attend York and U of T. Readers meet Kara when she is in the eighth grade, and follow her until she receives her university acceptance letters.

In The Student, Miriam Moscowitz’s parents live a couple blocks north of Eglinton on Heddington and she attends high school at North Toronto Collegiate near Yonge, goes to the movies at the Eglinton Grand near Elmsthorpe, parks with her boyfriend a few blocks south near Wychwood Park, and takes the bus back and forth to U of T, disembarking at Bathurst to walk home via Eglinton. Readers meet Miriam in her last year of university in 1957 (the second half of her story unfolds in 2005 and gradually reveals choices made in intervening years).

The young women have things in common. In Frying Plantain’s opening pages, Kara’s grandmother describes her as “a soft chile” and early in The Student Miriam describes herself as a “scared rabbit”. Kara tells stories (lies, some say) to “build different identities, personalities” and Miriam loses herself in stories, like Anne of Green Gables, “books about children whose lives she wishes were her own”. Kara’s grandfather watches westerns on TV and Miriam’s boyfriend watches them in the theatre. Kara’s boyfriend takes her to the movies too, at the SilverCity, and both girls navigate their burgeoning sexuality, negotiating and rejigging their partners’ expectations. Both ultimately leave midtown to further their education downtown.

In Frying Plantain’s first story, “Pig Head”, Kara struggles with the after effects of having elaborated on an experience she had visiting family in Hanover, Jamaica. Briefly, her story is a boon: she gains popularity at school, for her (imagined) daring, and peace in the neighbourhood, when her Jamaican friends temporarily overlook her “great misfortune of being Canadian-born.” She was not Jamaican enough to have lived the invented experience, not Canadian enough to dismiss being judged “soft” for that lack.

Because Kara is on the precipice of her teen years, she inhabits a swath of uncertainty from girlhood onwards. An awkward donut-shop bathroom encounter with a boy leaves her embarrassed and lonely. Although she doesn’t aspire to the “brand of pretty that turned guys into idiots”, she can’t “help but notice” those girls with their “flowy blonde hair, big-breasted and perky”. She also can’t locate herself in the drugstore make-up displays: “I couldn’t describe my own skin tone; people called me yellow. People who were nicer called me caramel. I had no idea what that translated to in powders.”

In The Student, Miriam’s boyfriend is frustrated when she discusses the moral ambiguity of the movie they watch: he accuses her of ruining the film. Because she cannot express what thrills her about watching and discussing Bergman and Kurosawa films, she cannot begin to explain her compulsion to engage with people whose worlds are even wider, those listening to jazz music and following the progress towards school integration in Arkansas.

In autumn 1957, Miriam askes a supportive professor to recommend her for grad school. Having dutifully studied Wolfe, Lawrence, Forster, and Maugham (another professor declares that Virginia Woolf is of interest only as a neurasthenic, not a writer), she longs to write and teach. But first she must convince “those around her she deserved to be one of them”. Her English professor refuses to recommend her for grad school: “You’ll get married and that will be the end of it. And a spot that could have gone to a genuinely worthy candidate will have been wasted.”

Kara, too, is angered by patriarchal entitlement: “…Oliver was a friend of my grandfather’s, and I bit my tongue when he squeezed my cheeks between his thumb and forefinger. I was old enough to drink, smoke, and vote but apparently looked young enough to pinch. I tried not to seethe.” Kara tries not to seethe; Miriam is angry, too, but other emotions hold sway in the moment. “I will not cry, [Miriam] told herself, I will not. She sniffed just once and managed to look straight at him.” She remembers another uncomfortable situation with a high-school teacher, something “she found impossible to tell anyone about”.

Kara’s and Miriam’s anger gathers as their timelines move closer. “Don’t interrupt me,” Miriam declares in her 2005 narrative (She declares herself “genuinely worthy” in other ways too, but the pleasure of The Student is in tracing Miriam’s route, her learning through late-20th-century writers like Cixous, Kristeva, Heilbrun, Sedgwick and Butler, her growth and experience). As time passes, in part because women like Miriam broadened academic borders, young women in Kara’s graduating class debate the merits of a variety of educational opportunities.

Miriam is aware of her separateness: she applies her eyeliner so that her eyes look larger (and her nose, in turn, smaller) and dates a boy who is “Jewishly handsome”. She acknowledges that her nuclear family’s rented vacation home is on the part of Lake Simcoe’s shore where Jewish families can buy property. But she also barely recognizes some of her privileges. She makes light of the plight of the young man, who is sponsored by her father to come to Canada, whose family was murdered in the war overseas. And she jokes about being so disinterested in fashion (she is “notoriously incompetent in the traditional feminine arts”) that she might as well wear a potato sack: a moment later, she recalls a photograph of a sharecropper’s child actually wearing one, an experience far from her reality.

Kara’s family is working-class, her father disengaged from her upbringing, and more than once she and her mother have to live with her grandmother. Her awareness of cost and value reveals that budget concerns simmer beneath daily decision-making; she and her friends work part-time, and she travels just once to Jamaica, where her family is from. Her part-time job at the HMV in Yorkdale Mall boosts their household’s bottom line, whereas Miriam works reception in her father’s office.

Both Reid-Benta and Fagan complicate their heroines’ lives. Both young women reach beyond the familiar. Both women experience loneliness and self-actualization, vulnerability and ambition, as they work towards belonging and independence and forge meaningful relationships with other women. Most importantly, Kara and Miriam insist on defining their own selves. They identify their desirable destinations and they drive their own narratives. They let go of banisters and, when someone moves the furniture behind the scenes, they don’t let it go. They stand independently and they hold their ground. It’s no exaggeration to say that I think of them often—their fierceness and their determination—as I walk on and around Eglinton myself. These are neighbourhoods I know well, and these women’s narratives are equally engaging: occasionally transformative, as they grapple with major decisions, but more often ordinary, and all the more relatable as such.

As much as I appreciate their stories, I appreciate the gaps in their structures as well. In Frying Plantain, Reid-Benta allows time to tumble between stories, enough time for street addresses to change and for relationships to sprawl and contract, to hint at the experiences of Kara’s family members at the edges of her narrative. In The Student, Fagan presents to the reader forty-eight unchronicled years in succession, in which to imagine a mid-life for Miriam. These spaces are the spaces which allow Kara and Miriam to cross my mind, as I walk the streets that they’ve walked on the page, the spaces in which their imagined stories can continue to unfold.

When she returns to the Eglinton and Marlee neighbourhood, years later, Kara observes: “It’s still the type of neighbourhood that never rests, never stays quiet.” The houses on the west side of the Allen Expressway are smaller, frame and brick bungalows, than they are on the east side, on Heddington, which has larger two-storey brick buildings with mature trees and garages. But all around Eglinton, in every direction, are women who never rest, who never stay quiet.

Marcie McCauley writes essays, book reviews and fiction, published in print in Orbis (UK), Room (Canada), and World Literature Today (U.S.) and online at The Empty Mirror, Literary Ladies, and The Los Angeles Review of Books. She is a Resident Reviewer at The /tƐmz/ Review and she also writes about writing at marciemccauley.com and about reading at buriedinprint.com. She lives and works in Toronto, on the traditional territory of the Anishnaabeg, Haudenosaunee, and Huron-Wendat–land still inhabited by their descendants.