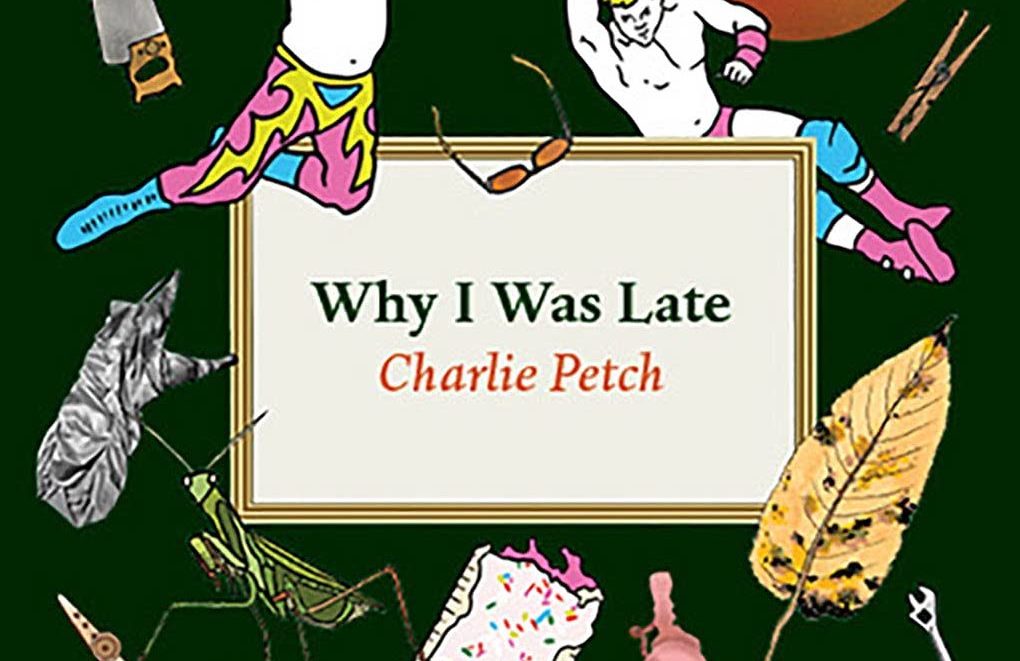

Why I Was Late

Charlie Petch

Brick Books, 2021

Review by Stella Cali

Charlie Petch’s debut collection of poetry, Why I Was Late, opens with a love letter to C-3PO. “I always thought you were gay,” says the speaker. “I imagined there was a / little glorious hole / somewhere in R2-D2.” The tenderness and humour that rings through this poem is a fitting introduction to the collection. The speaker looks with care, and that gaze, the willingness to see what someone really is, is an act of love in itself. To be truly seen is something which this collection encapsulates:

I felt your tears my sweet

though your face

betrayed

nothing

(“Dear C-3PO”)

A playwright and performer, Petch weaves elements of theatre and performance into the fabric of Why I Was Late. Some poems begin with stage directions or suggestions for musical accompaniment; “To be performed with a loop-pedal build on dulcimer and viola,” we are told at the outset of “The Ballad of Owen Hart,” or, in “Eat Prey Love,” “To be performed with an insect voice & stance.” Readers are encouraged to imagine the poem as performance, to engage with the piece on an auditory level and imagine it in three dimensions, on a stage or in a dark room.

Our attention is brought, in addition, to the idea of performance on a larger scale—of the freedom and restriction of roles. In “Schoolyard Theatre,” the speaker makes up part of the cast; “TEENAGERS are having a party … DAUGHTER is caught drunk with BOYS.” The speaker revels in “being the boy,” in “moments of male” that make them feel as though their “skin was drag.” While the other players vie for “parts” in the play, the speaker’s “body relax[es] / into boy.” The speaker is performing at all times—in this moment of theatre, they “finally / didn’t / have to / act.”

Performance and gender are explored at length—in “One Year Gender Queer,” the speaker explains:

I wear a costume every day…

I do work drag

drag to go shopping

drag to sleep drag to eat

Petch explores the sensation of the body as costume, of being denied the freedom of self through the prescription of a role. Boxes checked on a birth certificate, M or F, become boxes to be filled—cages into which we must fit—become boxes lowered into the ground, coffins for trans folks forced to perform the gender they were assigned at birth. The body and the self are physically restrained, contorted, forced to fit into a cis shape. “Would you like us even smaller?” asks “Translucency.” “Something that can / be shoved into a drawer / pressed into bible page.”

The body itself can be an antagonist, something which resists alteration and is at odds with the self. “I used to starve to be gender neutral svelte,” the speaker says in “One Year Gender Queer”—“I ran from my body / physiologically.” The speaker’s posture is altered by their relationship to gender—their neck and shoulders, once rolled forward and inward, are now pulled back. After puberty, breasts rob the speaker of their ability to be truly seen—to be perceived as they are. They change the shape of their body as a result, re-forming it through binding in a way that mirrors but opposes a moment in “In The Distance”—a poem exploring violence enacted against, and by, young boys. In the poem, three boys place a penny, a quarter, and a ring on the train tracks and wait for the train to flatten them, to “forc[e]” them into “shapes.” Freed by the noise of the train, one boy is “able to shriek / finally.”

As the body is a character in this collection, so is the brain, which undergoes its own physical traumas. Early in the collection, Petch explores brain damage as the result of a heart attack, and the change in personality that results; “your husband,” they write, “could come home / a stranger.” The brain functions as a source of frustration in the text, a part of the body we do not fully understand, outside of our control. “I have so enjoyed / my brain,” says the speaker in “Complicated Migraine.” “Days later / the world is shattered glass.” The speaker goes on to state that they approach this grief with humour—in the same way that humour goes hand in hand with empathy and strength across the poems in this collection:

I’ll laugh

until my last breath

because

obstacles

are punchlines

Underlying this collection is music—in the stage directions, in the background of poems, in the body of the speaker. Music is a source of connection between the speaker and a partner they lost—they hear their partner in the music of mandolins, the sound of violins. “When I hear our music / on the radio now,” they say, “it feels like I’m slipping / down stairs.” Music and sound serve to explore the complicated nature of relationships. At times in this collection, the body is an instrument, its music born of tension—just like the speaker’s relationship to their partner, manifested in the tension of a string pulled taut, a bow poised to play.

Petch approaches relationships of all kinds—between an individual and their body, their partner, their gender—with care. This collection, at times hilarious, at times deeply sad, seeks to understand beyond the surface, and presents its findings with compelling honesty.

Stella Cali is a queer writer and artist completing an MFA at the University of British Columbia. She lives and works on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and sel̓íl̓witulh Nations.