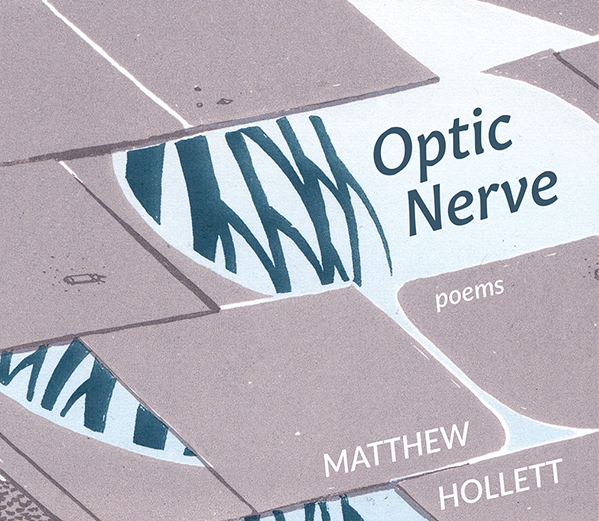

Optic Nerve

Matthew Hollett

Brick Books, 2023

Review by Stella Cali

In this collection’s final poem, writer and visual artist Matthew Hollett describes the intimate space inside a woodstove, “that blackened cave where images spark / and flicker” (“Woodstove”). This image pops up again and again; “your eyeballs squirm and fidget,” Hollett writes, “in that empty theatre where every unconscious hour / is spent waiting for a projectionist to get his act together” (“Prisoner’s Cinema”). This is the camera obscura—and in “Optic Nerve,” it’s our very own eye.

“Optic Nerve” explores the interplay between seeing and feeling, the relationship between the lens and the world outside it. Divided into three sections, “In Camera,” “In Negative,” and “In Print,” the collection examines our environment through a macro lens, takes a cinematic look at the sky, and runs its eye tenderly over things in plain sight. This collection plays and dances, inviting us to look closer, look farther—to close our eyes and observe the dark.

Hollett’s flora and fauna crawl and bloom through the pages of this piece. Wild things are rendered with humour and beauty; In “Wind in St. John’s,” the wind, depicted as a card shark, bluffs all night “til four in the morning when it crashes, blurs, / and curls up on a sandbar, outsnoring the foghorns.” “Frost” captures this frozen dew with energetic and crackling language, “a conspiracy of lickspittles, / frost sabre-rattles, embrittles, glitterbombs,” and the fungi in “Peer Gynt Peels the Mushrooms”—“you gilled dollops, moss-polyps, mud-scallops”—are rendered with slippery, primordial glee. In these poems we are prompted to take the long, slow look of a timelapse; to zoom in on our environment and explore its richness.

Layers of perception are at play, too, when Hollett’s gaze is turned on other seeing creatures. In “A Profusion of Handsome Japanese Papers,” we’re invited to consider these layers as the speaker states: “[H]ere’s an artist’s impression of how an octopus sees its garden.” In this scene, an artist creates an image of how they imagine an octopus might perceive what it sees; image-making and perception here are intimately intertwined with emotion and individual perspective.

Packed with striking images, Hollett’s poems are not only photographic, but prompt us to consider the experience of vision. “If you could play back every blink and blackout,” the poet writes in “Prisoner’s Cinema,” “days would flicker past / in time-lapse.” In the preceding poem, “Roll Over,” the speaker describes finding a coil of film in an abandoned cinema, the moving image of a “cartoon beagle spinning through a wild blue yonder.” In this poem the physicality of the film itself makes up the beagle’s experience:

By yo-yoing the filmstrip

on my finger, I trained him to somersault at half speed, or double,

and when I took him home he curled up in a film canister. I clipped

the mangled ends from his reel, so now when I take him out for a tumble

he isn’t scorched or torn when it ends.

These poems explore the framerate of our own experiences; how the act of seeing, and the eyes themselves, are modes of consuming and creating life. In “After André Kertész’s Central Park Boat Basin, New York, 1944,” the photographer’s work is both productive and devouring: “Kertész, at ninety, / asked why he was still taking photographs, / replied: I’m still hungry.”

Interwoven into the world of this collection are poems of the pandemic; Hollett embodies the isolation of lockdown and the collective trauma of Covid-19 set against the environmental changes that took place as the world slowed down. In “Tickling the Scar,” the speaker walks the Lachine Canal and observes the return of the blue herons and the algae. “Thousands of Montrealers / are drowning in their beds,” they say. “I walk the canal / because I’m grateful to breathe.” As the poem continues, the speaker reflects on the damage done, and the process of healing:

At CHSLD Herron,

a relief nurse finds ninety-year-olds so dehydrated

they’re unable to speak, with urine bags full to bursting.

They bring the army in, repurpose refrigerated trucks

as morgues…

I think of walking the canal as tickling the scar.

Tracing a fault line between “before” and “normal.”

There was a lake here, before it was torn

into an industrial corridor. A long blue lung.

It’s slowly healing over. You can sit on the grass

and watch herons stitch it back together

Tender and playful, these poems are an intimate interaction with all that surrounds us—inviting us to stop, blink, and look again.

Stella Cali is a queer writer and artist completing an MFA at the University of British Columbia. She lives and works on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and sel̓íl̓witulh Nations.