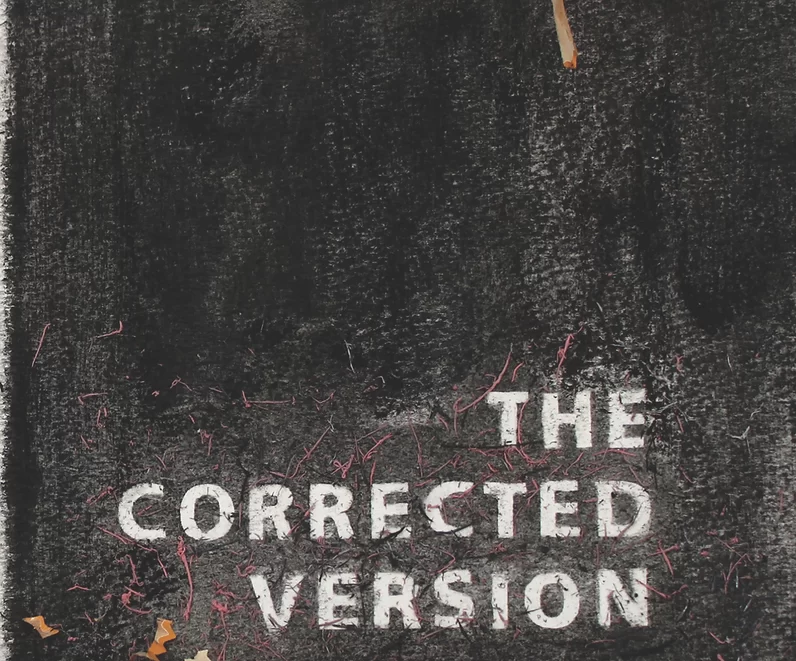

The Corrected Version

Rosanna Young Oh

Diode Editions, 2023

Review by Joanna Acevedo

The speaker in Rosanna Young Oh’s The Corrected Version has a complicated relationship with work. As she details the day-to-day experiences of working in her father’s grocery store, the poems expand and contract around her interactions with her father and her mother. Perhaps what is most exciting about this book is its scope: its ability to address large and small problems at the same time, sometimes even in the same poem. The speaker zooms out to address larger structural problems like racism, sexism, and politics, while at other times examining the very microscopic, such as lists of the fruits and vegetables they sell. Told in a conversational, methodical, and almost clinical tone, The Corrected Version meticulously details thoughts we have all experienced but have never had the language to verbalize. As a teaching object, it offers an intimate glimpse into another life from many perspectives—a truly impressive feat.

“Someone always has to mind the store.” This line, from the poem, “New Year’s Eve,” is the basic building block of The Corrected Version. The book is split into four sections, but this line recurs as the collection moves and changes its focus. Later in “New Year’s Eve,” Oh notes that the store is open 365 days a year. This kind of battering cycle of constant work is similar to the way that the poems function in this collection. Oh pulls no punches, powering forward with a relentless drive in a fast pace of short poems with brief, gut-punching lines. This drive is similar to her father’s work ethic. The collection is peppered with examples of Oh’s speaker working alongside her father; sometimes begrudgingly, sometimes with vigor, but always with respect for her father, and sometimes a little bit of pity for his tireless work. In the poem, “Erasures,” she says,

‘Greed must exist in the service of others.’

People say I am my father’s daughter—

perhaps the remark

is intended as prophecy.

Oh is sharp-edged in her realizations. She often cuts to the bone with the directness of her lines. Oh’s voice is unique as a contemporary poet, reminiscent perhaps of Monica Youn’s most recent work for the flat affect and direct way she speaks. The result is a narrator who explains ideas clearly and asks smart questions of the reader, without pandering or diluting her own ideas.

The title of the collection comes from the poem, “The Problem With Myth,” in which Oh details a familiar story: an angel comes down to earth to bathe in a pool of water, and a hunter steals her wings and rapes her, making her his slave and wife. There are, however, two versions of this story. In one, she is a rape victim being held prisoner, and in the other, she is the seducer, beguiling the hunter. The speaker’s father believes the second version, which he refers to as the corrected version. Oh is engaging with long-held beliefs about the role of women in service positions—that they are lesser, baser, and even in some cases, objects whose lives can be bought, sold, and traded. In many other parts of the book, the speaker references her father’s desire to be a writer—the very profession Oh and her speaker have taken on. Oh’s speaker and her father have switched roles. Her father has sacrificed himself in a service position—as the owner of a store he is at the mercy of his customers—all in order for his daughter to have a more traditionally masculine profession. Throughout the text, it is clear he feels emasculated, and his obsession with the store is an effort to desperately provide for his family. The speaker comments about her father in the poem, “Erasures”:

Maybe he’s erased too much of himself

in his pursuit of a “life” in the word’s

most conventional sense:

sacrifice, money, shelter.

She goes on to speak of his boyhood dreams of being a writer, the very career she has now achieved. Oh deftly manipulates these themes, often in brilliant, lyrical lines. Although lyric is clearly not the focus of Oh’s writing, she consistently has the powerful ability to turn a phrase—another pleasure of this collection.

Current events are quietly woven into the fabric of this collection, and while it may feel both ultra-recent and incongruous to speak on these issues, especially with all the moving parts that are going on in this collection, Oh manages to keep all her balls in the air, and this section of the book feels robust and well-constructed. Oh addresses the coronavirus pandemic in the middle of the book. She describes how her father actually profited from the crisis as people flocked to grocery stores for supplies. She also briefly touches on race, in the poem “Hard Labor”: “To the customers at the store / I respond I am not Chinese / with the same confidence / as when I inform them, / this melon is from California.”

The fourth section of the collection feels the most tonally different from the rest of the book. In this section, Oh details the speaker’s parents’ experience of old age. Additionally, there was a feeling of unresolvedness to the writing, as if Oh herself had not completely worked out the emotional aspect of this part of the book. In “Eternity,” however, her final lines were sharp, strong, and confident: “I ask, Where will you live now, in the past or the future?” / You answer, “Neither.” The contrast between the directness of this question and the ambiguity of the answer smartly ties the collection together; it is a wonderful meditation on grief and gives the reader an answer without actually answering anything at all. As a philosophical question, it’s fascinating, and it leaves the reader with a lingering sense of wonder.

This collection is smart, readable, and full of clever writing. Oh carefully weaves themes such as sexism, racism, labour, and the American Dream into a conversational tone that consistently surprises the reader with its ironic humor and ability to engage with difficult topics. Oh has clearly established herself as a writer to watch.

Joanna Acevedo is a writer, editor, and educator from New York City. She is the author of two books and two chapbooks, and her writing has been seen across the web and in print, including in Jelly Bucket, Hobart, The Rumpus, and The Adroit Journal, among others. She received her MFA in Fiction from New York University in 2021 and also holds degrees from Bard College and The New School.