Incrementally

by Penn Kemp

Hem Press, 2023

Review by Richard-Yves Sitoski

“Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer; they feed energy back and forth and amplify it.” – Ursula K. Le Guin

Who hasn’t played with a Mr. Potato Head? The best part about it is in creating pseudo-Cubist chimeras with multiple mouths, or arms, where the nose should be. When folks do that, they are engaging with the idea that categories only exist in so far as we let them and that using play to reject categories, canons, and unquestioned principles can be one of the best ways to make use of a mind that has received training in The Proper Way To Do Things. With Incrementally, Penn Kemp pushes this to the limit; she plays with play itself, both as idea and act.

Full disclosure: I am a frequent collaborator with Penn Kemp, having most recently co-edited with her Poems in Response to Peril: An Anthology in Support of Ukraine. Though that was a more conventional book, it included QR codes to an extensive YouTube playlist, and so it was in keeping with Kemp’s multimedia praxis. For her, Incrementally is a project consisting of a book which is available in hardcopy or downloadable as a free ebook and a series of audio recordings, both of which should be experienced simultaneously. Not simply because they inform each other, but because they combine in creating a multi-modal whole. The haptic qualities of a book address our senses of touch and sight, while the recordings move us aurally through time and linguistic flux. This is sound poetry that uses a score. The written text is not so much a book to read as one to watch, in the way that looking at a sculpture from all angles is a form of watching the play of light and shadow and how form changes with perspective.

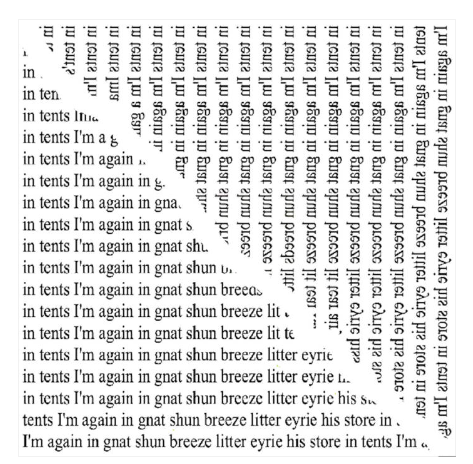

The poems work in many ways, though especially as the title states, through a process of incremental change; addition, subtraction, multiplication, conflation and isolation of phonemes and morphemes. This is gut-level poetry, literally. Even when the poems use identifiable verses, they are always meant to be thought of in their component breaths. Language begins in exhalation, finds its cradle in the diaphragm. Many of the sounds in the audio files of Incrementally are reminiscent of breathing exercises, animal noises or natural sounds, which are their own form of artistic orality.

The development of the poems is agglutinative, in that disparate elements are brought together to create wholes greater than the sums of their parts. It is because of this that the written text must accompany the aural version: lines lengthen as the poems go on, as one sound is added to the next with each line, and as puns, rhymes, homophones and homographs insinuate themselves. The graphic quality of the words on the page is crucial to the overall effect and can lead to manifold delights, especially when it comes to how Kemp, in a sense, pushes onomatopoeia beyond sound to include sense. To write, read, and hear “through” as

thro00000oooooooooooooooooooooo0000000000000000000ooo

ooooooooooooough thro00000ooooooo0000000000000000000ooo

ooooooooooooough

is to truly go, well, through “throughness”.

What follows from this is a representational paradox: a word may be arbitrary when treated in isolation or as pure sound, but the way a poem works requires us to operate from the (tacit) consensus that language exists as an entity; self-supporting, self-defining, self-constructed. The Dada movement, with its love of satire, got a lot of mileage out of that and blew up language for principally political reasons while Kemp disassembles language then reassembles it for a myriad of reasons; political, social, cultural, spiritual among them. As did the Dadaists, Kemp makes a virtue of spontaneity, but the semantic qualities of the uttered word (its ability to generate context) are crucial. And so the only thing left up to chance is chance, and the poems bootstrap themselves into shifting meanings as the lines progress. For this reason, if you are not able to read along to the audio recordings, you should endeavour to read this book aloud–so much the better in a public place like a café or library!

Puns and homophones are among Kemp’s favourite tools and they function in a delightful manner. They are hinges, folding one way or another around the pin of sound to create multiple possible meanings within the lines and in their immediate and larger contexts, each of which informs and is superseded by the following one in the process of endless evolution. The puns never permit you the luxury of complacency. You think you know a word, but you don’t really know it until it is replaced by a word which can pass for it on the street, but which decidedly isn’t it.

The wordplay succeeds also because Kemp is very much aware of the tension between connotation and denotation. In Incrementally these are deployed with minimal syntax, which is treated more as a suggestion than as a structure, or maybe even bloatware (the unnecessary software that tech firms seem to perversely enjoy using to clutter up useful apps). In other words, something we can safely delete in order to appreciate the juxtapositions of sounds as chunks of meaning, or simply as sounds. The incremental, agglutinative configuration of the lines (that is, they way they are assembled from discrete elements to create larger and larger wholes that surpass their combined meanings) stands in for the rest of syntax, and the concrete shapes on the page contrast with the abstract images evoked.

Further, not just here but in a lot of her work, Kemp has a ball with etymology and philology. Poems are constructed around the interaction between historical and current meanings, and around the afterlife in English of foreign loan words. Consider the following, from the poem, “A Tune”,

res

reason

reason ate

reason ate thing

resonating

What could be more fundamental to a sound poem than res, the Latin word for “things”, or collectively, “thing”? All the more considering its almost endless set of denotations and connotations, most if not all of which apply: “matter”, “fact”, “item”, “object”, “circumstance”, “reality”, “validity”, “truth”, and “substance” among them. Because of these meanings, res is what is primordial, what precedes reason. There is no comprehension without a world to comprehend. And yet look what happens when reason is let loose upon the world: it consumes it. Res is lost in reason. It’s not a stretch to see this as a veiled comment on the limitations of our capacity to reason, if it is divorced from what it is not (presumably feeling). Yet this consumption does not put an end to things, for it too is generative of poetry, of resonance. We can say positively that if your faculty of reason can contain (comprehend) the world, then you have the potential to create it. And how do we know this? Because Kemp sets it out in glorious technicolor in the following poem, “Lacrimae Res”, “resonating within the confines of our chest cavity even a perfect / note sounds”.

This is poetry which breaks down the distinction between the sensory and the sensual. It originates in the body and impacts it in a feedback loop. Kemp is not afraid to celebrate the procreative,

me

moves

me move bawd

me moves body

and

Annie muss

Annie might Annie must

Animus must mate some night

There’s no end to the joy, the jouissance, because ultimately any act of artistic creation is in defiance of death. Poems are composed in DNA codons; they are the expression of beings who want to survive, thrive, and reproduce. The advantage of artistic production is that, unlike human reproduction, it is potentially more sustainable. Listening to the audio files or reading the PDF impacts the environment, but not in the way that the production of paper books does.

Kemp coined the term “sounding” to describe her approach to poetry, meaning at once the production of sounds and also the use of sound to plumb and investigate the universe around us. This is what Incrementally is all about. It’s a project that requires you to engage with it, and in so doing engage with your own body as a way of engaging with the wor(l)d. It is play of the most serious sort. Play as discovery, as heuristic, but also as a generative act, and end in itself.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Richard-Yves Sitoski is a poet, songwriter, playwright and performance artist. He was the 2019-2023 Poet Laureate of Owen Sound, on the territory of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation. His poems have appeared, or are forthcoming, in The Antigonish Review, Arc, The Fiddlehead, Prairie Fire, Train, CAROUSEL, and elsewhere. He is co-editor, with Penn Kemp, of Poems in Response to Peril: An Anthology in Support of Ukraine (profits from which went to displaced Ukrainian cultural workers). He is the Artistic Director of the Words Aloud Poetry Festival in Grey County.