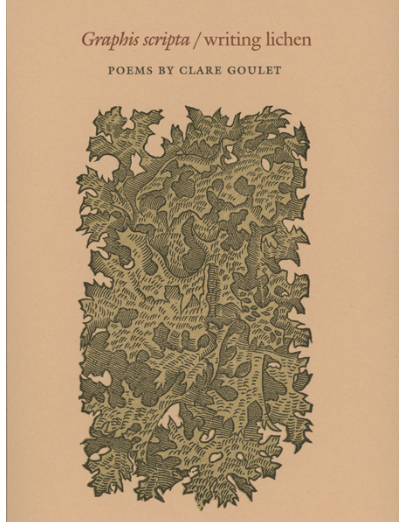

Graphis scripta / writing lichen

by Clare Goulet

Gaspereau Press, 2024

Review by Kim Trainor

Clare Goulet’s first poetry collection, Graphis scripta / writing lichen, draws its title from a lichen found in wet coastal forests, known by its common name of ‘script lichen’ or ‘secret writing lichen’. You may have encountered it, carbon black hieroglyphs on paler deciduous bark like the mad scribbles of a grammatologist. My Mosses, Lichens & Ferns of Northwest North America field guide offers a more technical description, “As the name implies, ‘pencil marks’ describes the narrow, elongate fruiting bodies (lirellae) that distinguish this crustose species.”

For the uninitiated, lichens are defined as a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship between fungus, algae and/or cyanobacteria, and, as we have recently discovered, yeast. Fungus forms the largest material component of the lichen. It consists of densely woven filaments that embrace the photosynthesizing algae and/or cyanobacteria which generate the necessary energy from sunlight to feed the whole. Lichens assist in the recycling of nutrients through the ecosphere and draw sustenance from dust and rain.

Lichens raise fundamental questions about organisms and their relationships to their ecosphere, symbiosis, communalism, parasitism, part versus whole, emergence, and epistemology as so beautifully described by Trevor Goward’s influential “Twelve Readings on the Lichen Thallus.” Clare Goulet’s book will be a similar delight for the initiated and possibly a greater challenge, hopefully, an invitation for those who rarely notice these beautiful skins that adorn so many of the world’s surfaces in variegated patterns and colours.

The tour-de-force of the book, “Index of Names,” offers a poetic typology of lichen, poems arranged in alphabetic order by Latin name; the common names are gorgeous—asterisk, blue felt, elf-ear, sea tar, black woodscript. Each poem is an exercise in close, loving attention. Her technique relies on ekphrasis; the ekphrastic method is the translation of a work of art into poem, although in ancient Greece, the term ‘ekphrasis’ (etymologically, from a Greek word meaning “I describe, I point out”) referred to the skill of describing any thing in a vivid and detailed manner. Goulet applies this approach in “Index of Names” to a range of foliose, fruticose, and crustose lichen. In each poem, details are layered line after line by means of careful metaphor and imagery.

There are benefits and challenges to such a method: one benefit comes from the close attention paid to these lichens in such beautiful detail, each poem an embroidered gem. This attention is first practised by the writer (and I think it is often the writer who most benefits, where writing becomes a form of meditation) and secondly by the reader, where the novelty of description might open new ways of seeing. One challenge might come from being unfamiliar with the particular lichen being described, although this can be somewhat overcome with use of a field guide or a quick image search.

Consider the poem “Cladonia bellidiflora / la pâquerette,” short and sweet, consisting of four brief stanzas in which each line offers an apt metaphor to describe the lichen’s ruffled fleshy tubes with its lipsticked tips. “Burlesque grotesques” are “rouged inflated flirts // bustiered.” They are “not even trying to hide / their clear desire: a glass jar / of rococo candy mouths.” They are “scarlet peonies, full blown” and the “grin in Mae West’s gaze // as she mouths the word / (it must be said) / obscene.” This poem, quoted here in its entirety, feels like a magic trick, lichen metamorphosed into the exigencies of desire. But it also raises questions about what forms of attention we might bring to the lichen through poetic licence, to what extent metaphor obscures or anthropomorphizes, as much as it focuses the attention or allows for a new kind of seeing.

The collection’s eponymous–and finest–poem, “Graphis scripta / writing,” is a longer meditation in five parts on script lichen. It begins with a concrete scoring of words on the page to describe the process of photosynthesis, “and and hydrogen and carboncarboncarbon and / and / and oxygen carbon and hydrogenhydrogenhydrogen”. Goulet then employs metaphor, lichen translated into a verbal analogy, as if a poetic version of the algae’s miraculous translation of sunlight and carbon into carbohydrate–that is, algae transform these elements into carbohydrates (the lichen thallus); similarly, the poet takes the lichen and transforms it into language–words and metaphor. As with “Cladonia bellidiflora,” the choice of metaphor here is apt, precise, and pleasing, “as if / overnight scribbles / on the bark like a flash mob / after rehearsing for weeks / Presto!” and “magic / mushroomed letters / written in crystalline / chitin delicate as / scallop shell as insect / wing.” The human parallel here, likening overnight scribbles to a flash mob, is amusing and fun, analogous to Mae West mouthing the word “obscene.” However, “Graphis scripta / writing” interjects a more sombre note, “as if the bark / had something to say, / as if we could hear” which grounds us and leads us to ask, what might the lichen have to say? How might we hear or learn to read this scribbled message?

The poem then shifts to a direct quotation from a 1904 nature guide, Guide to the Study of Lichen, which describes looking at “black-letter characters” under a microscope, “and you will see to your astonishment that it consists of a number of upright cases like miniature peapods.” “Graphis scripta / writing” then moves from the metaphor of writing to that of agriculture and the chemical syntax of lichen, describing lichen’s powerful ability to use hyphal threads to penetrate rock and human-made surfaces, where decomposition and reconstitution become forms of translation, “night syntax labours in a long tunnel, leaving tiny gaps in its timber- / prop polymer walls to pass tools through to the rockface.”

Goulet’s collection ends with a single poem, “Well,” dedicated to Warren Heiti and his 2021 book, Attending: An Ethical Act. As with the collection as a whole, this poem asks, “What matters– / what we discover, bring home, name? / Or our attention to a thing / that is not us? Or is it / the thing itself, / LICHEN Pinaftri / already knowing / all it needs, / having written itself, / poem and poet both—”

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Kim Trainor is the granddaughter of an Irish banjo player and a Polish faller who worked in logging camps around Port Alberni in the 1930s. Her fourth book, A blueprint for survival, appeared with Guernica Editions on 19 March 2024. Her poetry films have screened in Dublin, Athens, and Seattle. A current project is “walk quietly / ts’ekw’unshun kws qututhun,” a guided walk at Hwlhits’um (Canoe Pass) in Delta, BC, featuring contributions from Hwlitsum and Cowichan knowledge holders, artists, and scientists.