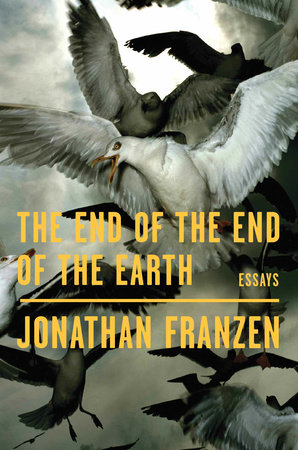

The End of the End of the Earth

Jonathan Franzen

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018

Review by B.H. Lake

Jonathan Franzen has been called many things. In 2010, his picture appeared on the cover of Time magazine next to the words: “Great American Novelist” and Sam Tanenhaus of The New York Times hailed his novel Freedom as “a masterpiece of American fiction”. His 2001 novel The Corrections won the National Book Award, and was a finalist for both the 2002 Pulitzer Prize and the 2002 PEN/Faulkner Award. Although The Corrections was published the week prior to the September 11 attacks, it was heralded as the novel that captured the anxiety of the post-9/11 generation.

He has also been called “arrogant”, “privileged” and, most recently, “climate fatalist”. He was handed this new label when, in his New Yorker essay “What If We Stopped Pretending (The Climate Apocalypse Can Be Stopped)?” he wrote about climate change and challenged the ways in which society was tending to the problem.

In the essay, Franzen writes: “The goal has been clear for thirty years, and despite earnest efforts we’ve made essentially no progress toward reaching it. Today, the scientific evidence verges on irrefutable. If you’re younger than sixty, you have a good chance of witnessing the radical destabilization of life on earth—massive crop failures, apocalyptic fires, imploding economies, epic flooding, hundreds of millions of refugees fleeing regions made uninhabitable by extreme heat or permanent drought. If you’re under thirty, you’re all but guaranteed to witness it.” What follows in the article are examples of the ways in which this could be true.

But Franzen offers a caveat to all of this. A better title for Franzen’s article might have been “What If We Stopped Pretending (The Climate Apocalypse Can Be Stopped If We Don’t Change How We Think)?”. He claims that the upcoming calamity is inevitable only if we do not change the way we think and he discusses our society’s refusal to do this.

In the days following its publication, the article raised the ire of critics all over the world. Critics from a number of publications wrote their own opposing articles, slamming Franzen for what they saw as “climate fatalism”. One such article, written by Drew Pendergrass in Current Affairs was entitled, “Franzen’s Privileged Climate Resignation is Deadly and Useless”. Pendergrass writes: “Franzen is not wrong to be pessimistic about our future. Global emissions continue to rise, making the 2030 target feel wildly optimistic. Even the Paris Agreement’s more relaxed goal of limiting warming to 2 C seems unlikely at best. But Franzen is dangerously wrong to conclude that all climate mitigation is useless.”

In my reading, Franzen does not conclude that all climate mitigation is useless. He is simply suggesting a change in tactics. He insists that what we want and what we say we want seem to be two different things.

So, given the fierce reactions his writing has received, it stands to reason that the most accurate description of Franzen was uttered by Franzen himself on his website’s homepage: “risk-taking essayist”. The pieces included in his latest collection, The End of the End of the Earth (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018), back up this claim. In them, he tackles the atmosphere in New York City immediately following the September 11 attacks, reflects on Edith Wharton, and his past friendship with author William T. Vollmann. He talks about his time birding in Ghana during the election of Donald Trump, he gives advice for writing literature in an age of distraction and too much ease, and he reflects on life, love, and wildlife while on a trip to Antarctica.

Franzen has said that The End of the End of the Earth is about death. That is true to a point, but what underpins this collection is a celebration of life and the natural world. The collection’s third essay, “Why Birds Matter”, is a plea for humans to not allow birds, those already endangered and otherwise, to become simply an unfortunate casualty in the fight against climate change. He implores us not to shrug off their plight and decide that “it’s too bad about the birds, but human beings come first”. He writes:

“What bird populations do usefully indicate the health of is our ethical values. One reason that wild birds matter—ought to matter—is that they are our last, best connection to a natural world that is otherwise receding (…)If we’re incomparably more worthy than other animals, shouldn’t our ability to discern right from wrong, and to knowingly sacrifice some small fraction of our convenience for a larger good, make us more susceptible to the claims of nature, rather than less? Doesn’t a unique ability carry with it a unique responsibility?”

In “Ten Rules for the Novelist”, Franzen offers an excellent short list of advice for writers, but some of the points on the list would serve anyone in their daily life. This is particularly true for Rule Number Seven: “You see more sitting still than chasing after”; and Rule Number Ten: “You have to love before you can be relentless.” Here, the best piece of advice is Rule Number Eight: “It’s doubtful that anyone with an Internet connection at his workplace is writing good fiction”. Franzen is not disparaging the individual talents of other writers, but rather is taking into account the human capacity for distraction. Franzen himself works on a laptop that he has rendered incapable of accessing the Internet. Other writers have admitted to physically disconnecting their routers before sitting down to work. This reviewer types out all of her first drafts on a typewriter, and the very fact that the SelfControl app exists should tell us that Franzen makes an important point here that many of us would do well to heed.

Franzen switches gears in his essay, “A Friendship”. When he was a young writer in the 1980s and 1990s, he shared a big brother/ little brother relationship with William T. Vollmann that teetered on hero worship. The essay is a remembrance of things past, a love letter to Vollmann—both the man and his writings—and is a testament to discovering one’s own identity in spite of outside influence. It also serves as a meditation on regret. In the essay’s final pages, Franzen recounts the time that Vollmann suggested that he and David Foster Wallace join him on a camping trip in the Salton Sea, which is, in Franzen’s description, “one of the foulest-smelling and least camping-friendly places in the country”. Franzen made the suggestion to Wallace, but he was not interested. Today, Franzen admits that this was a missed opportunity: “Only much later did I see that Bill’s proposal had been brilliant, and [I] regret that I hadn’t pressed David harder…I wished that I could step, for a few days, into an alternate universe in which I camped there with my two gifted friends, a universe in which both of them were still alive and might start their own friendship”. This story resonates not only with those of us who still feel the loss of David Foster Wallace, but also for those who recall missed opportunities like these in our own lives.

In the title essay, “The End of the End of the Earth”, Franzen receives an inheritance from his Uncle Walt and uses the money to take a three-week Lindblad National Geographic expedition to Antarctica. He describes the expedition leader running around for the duration of the trip and trying to provide “the great adventure” to those on board, the constant flurry of planned activities, and the other passengers looking to the establishment to provide the product they paid for: the product of fun. Franzen weaves into this essay the story of his Uncle Walt: a man whose life rarely went the way he wanted, a man whose story might be viewed as tragic. But Walt did not see it that way: “Walt lost his daughter, his war buddies, his wife, and my mother, but he never stopped improvising. I see him at a piano in South Florida, flashing his big smile while he banged out old show tunes and the widows at his complex danced. Even in a world of dying, new loves continue to be born”.

The essay brings to mind David Foster Wallace’s “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again” but turned on its head. Franzen watches the pursuit of promised fun happening around him on the trip but, rather than growing despondent and disillusioned, he separates himself from the crowd. The high point of the essay comes when he thinks he spotted an Emperor Penguin on an icefield. He tells those in charge, they turn the ship around, and he turns out to be right. The exuberance that followed gave Franzen “an inkling of how it must feel to be a high-school athlete and come to school after scoring a season-saving touchdown”. The reader feels it too.

Several times in these essays, when Franzen spots a rare or sought-after species, he turns to his companions and, overcome with joy, they high-five. The image of grown men high-fiving over seeing a bird or penguin sums up the spirit of what Franzen is trying to communicate in this collection. These are the moments that reveal where his heart lies.

In The End of the End of the Earth, Franzen does not tell the reader merely what they want to hear. He tells the truth as he sees it—whether or not his opinions reflect the status quo. In the title essay, Franzen writes that literature “invites you to ask whether you might be somewhat wrong, maybe even entirely wrong, and to imagine why someone else might hate you”, but what literature asks us to do is unpopular in today’s culture. Jonathan Franzen is no one’s echo chamber and for this, whether right or wrong, he deserves respect. I believe that the core of the online criticism of Jonathan Franzen may lie in the fact that he has told us things we do not want to hear and, on some level, we know that he is right about some of those things. No one likes to be woken from a deep sleep, even if that slumber is a fitful one.

B. H. Lake is a Halifax-based writer whose publications include The Furious Gazelle, Write Magazine and Atlantic Books Today. She spends her days working on her upcoming novel, In The Midst of Irrational Things.