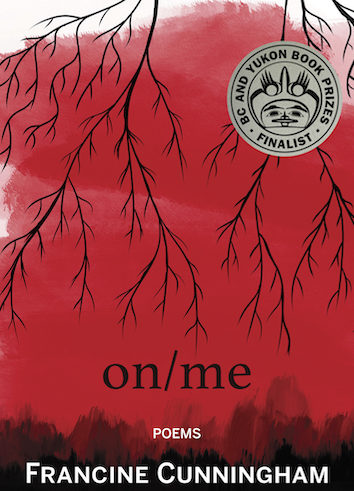

on/me

Francine Cunningham

Caitlin Press, 2019

Review by Kim Trainor

Let’s start with the title: on/me. Every poem in the collection has two titles: a main title that suggests a general category (On Grief, On Love, On Identity, On Mental Health) and a subtitle with a more precise title in italics (klo-NAY-zeh-pam, Ancestral Power, Love Letter 1). So, for example, “On Secrets / Things I Love About Myself.”

Francine Cunningham explains her naming and ordering technique in an interview:

I just really wanted to create this guide to some of the parts of myself that I felt like I needed to share. The poems weren’t grouped by theme to begin with, they came out all over the place and were sitting as single files. When the time came for assembly, I read them and tried to define in one word what they were about, which was when they got their “On” designation. I knew right from the beginning that the main thread of the book was going to be my identity, so the “On Identity” poems acted as the spine. All the designations have their own narrative arc when read in their own order, though, so if you were to read the “On Grief” poems, for instance, there is a story inside of that of my own healing.

There is something charming and frank about this accessible approach, a little reminiscent of Sei Shonagon’s Notes from the Pillow, an eclectic collection of lists and anecdotes like a fragmented diary. And on/me does read very much like a young writer’s diary, preoccupied, as many first poetry collections are, with an exploration of identity (“Cree,” “Metis,” “white passing,” “PTSD,” “bipolar ii disorder”) entwined with memories of childhood and family anecdote. As you come to read through the collection, the title does indeed come into focus, the book a first edition of a manual or guidebook to Francine Cunningham. There are some misses—in particular, a fair number in the “On Love” and “On Writing” categories––where the observations are prosaic, guided more by conventional narratives associated with these topics. But a substantial number of poems, both light and heavy, show Cunningham at her best work, writing towards an understanding of who she is, within a complex history of mental illness, rape and PTSD, and the legacy of colonialism.

First the light. Take, for example, “On TV / WWE”:

if my grandpa was in the living room

wrestling was on

This is short and sweet, with one perfect detail capturing the essence of her grandpa. These family vignettes provide us glimpses into the poet’s younger self, while other poems sketch out a narrative of what seems to be a long and patient, at times unrequited, love. These variegated glimpses, from love to TV, from childhood to young womanhood, mirror the shifting, constantly mutating facets of identity, befitting a collection that is charting this very self.

Here’s another glimpse, “On Love / Planting”:

when you plant a seed

you don’t see the whole of the tree right away

the fruit is not able to be harvested

until the year and season are right

i’ve planted seeds all over you

The last line, standing alone, balances the first four with its playful yet serious intention, while “i’ve planted seeds all over you,” is charming in its slightly unexpected turn of phrase––not “in,” but “all over you.”

Now for the heavy, one short and one long. These are also threaded throughout the collection. Here’s the short one, “On TV / Pocahontas:”

going to my granny and grandpa’s

so proud to show them

other natives on tv

they were sad

A child’s eye view is perfectly captured in these four lines; the child closely observes her grandparents’ reactions, absorbing but perhaps not yet understanding the complexities of representation and visibility, and the poet faithfully records this without analysis, in solidarity with the child.

The long poem, excerpted below, is called “On Grief / Hospital Visits,” and is painfully relevant in light of the recent report of widespread Indigenous-specific racism and discrimination in the B.C. Healthcare system (In Plain Sight: Addressing Indigenous-Specific Racism and Discrimination in B.C. Healthcare). Throughout her collection, particularly in the poems titled “On Identity,” Cunningham explores her experience of being of mixed heritage—Cree, Métis, Dutch, German, Scottish—but severed from her Indigenous traditions and the Cree language, able to “pass” as white. So identity becomes caught up in family, in language, in government forms and boxes to tick, in epithets and curses, and in this poem, in the medical system. Here Cunningham describes her mother’s experience seeking a diagnosis for the pain in her chest at a hospital over the course of a year. Her mother, who “never had a chance to be white passing / she was always known by the brown in her skin, / the cree in her features, / what strangers thought she was,” is misdiagnosed with each visit with a pain which turns out to be lung cancer, caught in the end too late as it has spread to her brain and her spine:

when she got sick, really really sick,

she went to the hospital

and they didn’t see the details then either

so used to “fixing up” the problem brown people

they didn’t see the real her

so they sent her away

and so she came back

again

and again

and again

and they always sent her away

pneumonia

that’s what they called her lung cancer until she couldn’t breathe anymore

As Cunningham describes, the health care workers can’t see her mother past the surface of her brown skin and the “cree in her features” which allow them to automatically place her in a box already labelled with their own misperceptions; in the end, such misperception may have taken her life, just as Cunningham’s grandmother’s life began by being taken from her parents and placed in a residential school, just as the colonial legacy has taken Cree from the poet, a language that slips through her dreams. This poem encapsulates the central puzzle that Cunningham’s collection is dedicated to working out, that “everything that is me can’t be put into separate boxes / i can’t be spelled out in the blank space of a form” (“On Identity / Together.”)

To return to the analogy of a guide or manual to the poet herself, on/me shows us the work in progress of a poet writing along her spine of identity and into a new space beyond such categories and confinements.

Kim Trainor is the granddaughter of an Irish banjo player and a Polish faller who worked in the logging camps around Port Alberni in the 1930s. Her second book, Ledi, a finalist for the 2019 Raymond Souster Award, describes the excavation of an Iron Age horsewoman’s grave in the steppes of Siberia. Her next book, Bluegrass, will appear with Icehouse Press (Gooselane Editions) in 2022. She teaches in the English Department at Douglas College and lives in Vancouver, unceded homelands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.