Summer Writing Prompt: Week 4

No, you may not use ‘a sore throat’ in your list. If you’re stumped, keep rewriting the last word until something comes.

No, you may not use ‘a sore throat’ in your list. If you’re stumped, keep rewriting the last word until something comes.

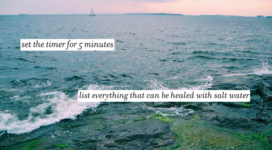

Olga Holin sat down with our PRISM international Creative Non-fiction Contest judge Jonathan Kemp and spoke to him about his writings and what he is looking for amongst the entries.

Interview by Erin Steel,

Sarah Selecky is a vegan, a Virgo, and a lover of dark chocolate. But she’s more well-known for her writing and her teaching. The New York Times called her first book, This Cake Is for the Party, “utterly fascinating.” This collection of short stories was a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Commonwealth Prize for Best First Book in Canada and the Caribbean, and was longlisted for the Frank O’Connor Prize. Her writing has appeared in The Walrus, The New Quarterly, and The Journey Prize Anthology. Through Sarah Selecky Writing School, she runs online creative writing and mentorship programs, and an annual international writing contest. Her new novel Radiant Shimmering Light will be published by Harper Collins Canada in May 2018.

Continue reading Writing Light: An Interview with Sarah Selecky

Our “BAD” themed issue will be on stands soon, and includes work by some of Canada’s most talented and thought-provoking emerging writers. This issue is an invitation to reconsider our biases and values, and to test the limits of...

Interview by Kyla Jamieson

Emerging writer Marc Perez’s story “Dog Food” appears in our “BAD” issue. Of his story, Perez says, “I once had a dog, and I named her Bruce. The story is a lament for her.” For this issue, we sought work that took us to true places along difficult or unexpected paths; “Dog Food” is one such story. In it, a boy witnesses violence he’s helpless against, and is denied understanding in the aftermath. His pain is real, but nobody sees or acknowledges it; where can it go but forwards, into his future?

Marc Perez immigrated to Canada from the Philippines and now lives on the unceded territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. Perez has been working in the nonprofit industry for the past five years; in addition to this work he is currently participating in Writing Lives, a project in which writers collaborate with Holocaust survivors to write their memoirs. Read on for Perez’s thoughts on identity and home, privilege and marginalization, and the best time to write—while asleep and dreaming.

Heart Berries

Terese Marie Mailhot

Doubleday Canada

Review by Cody Caetano

Often when I’m reading memoir, I’ll remember a quote from a misguided Neil Genzlinger, who penned “The Problem With Memoirs” for The New York Times in 2011: “There was a time when you had to earn the right to draft a memoir… Sure, [Amazon] has authors who would be memoir-eligible under the old rules. But they are lost in a sea of people you’ve never heard of” (italics mine). It is important to note that marginalized memoirists, especially early-career Indigenous women, Two-Spirit, and queer folks, have fraught histories with Genzlinger-types, their “old rules” and antiquated tastes that mar the merit of writing, publishing, and participating in the predominantly white spaces of the literary world. And then along comes Terese Marie Mailhot, a Salish First Nation woman from Seabird Island Indian Reservation with the assertion that memoir “functions as something vulnerable in a sea of posturing” (137). And it is in vulnerability that Mailhot effectively rejects the moth-eaten straightjacket that would otherwise restrict the inventive, decolonial confession of Heart Berries.

Continue reading Decolonial Confession: A Review of Terese Marie Mailhot’s Heart Berries

Interview by Matthew Kok

Beni Xiao is a nanny and writer based in Vancouver, BC. They are tired all the time, so they would appreciate if you’d let them sleep. Bad Egg, Beni’s new chapbook, is full of quiet, important things. There is a garden of variety in these poems, and the chapbook is drawn together by the strength of Beni’s voice. The effect is a lot like having a small bug perched in your ear, joking, encouraging, asking. They are willing to go with you into storms. They will not lie and tell you your impact on the world is going to be anything other than what it is. They will tell you about the hard, strong thing we all need to be sometimes, and as they describe it you may believe it is you—it may depend on the day, or whose limbs you’ve found crossed over your own, but the bug will say it for you if you can’t. There is a whole world of people who will speak around the important things rather than to them, or ignore the strange and the wonderful, but none of them are in this chapbook. You should start listening to Beni Xiao—I promise it will be worth it.

The Boat People

Sharon Bala

Penguin Random House

Review by Anjalika Samarasekera

In the second half of The Boat People, a Sri Lankan immigrant—and former Tamil Tiger—poses a question to his Canadian-born niece: “What do you think happens when you terrorize a people, force them to flee, take away their options then put them in a cage all together?” (230).

The question is the ravaged heart of Sharon Bala’s remarkable debut novel, which chronicles the arrival of around 400 Tamil refugees on the coast of British Columbia in 2010. The refugees have fled persecution in Sri Lanka following the end of the twenty-six-year civil war and have come to Canada hoping for a warm welcome. These hopes are dashed when the Canadian government detains the refugees on the suspicion that some of them belong to the LTTE, also known as the Tamil Tigers, a listed terrorist organization. Eventually, some refugees are released and deemed “admissible” to Canada while others are deported back to Sri Lanka.

Continue reading The Survival of Arrival: A Review of Sharon Bala’s The Boat People

Interview by Emma Cleary

Welcome to the first installment of Between Us, a conversation series by, for, and between immigrant/first-gen Canadian writers. We’re featuring writers who move back and forth across the hyphen, straddling old country and new, negotiating ideas of home-place, belonging, and identity. Writers who create within and beyond the categories of “Canadian literature” and “Canadian immigrant literature.”