Review by Kyla Jamieson

even this page is white

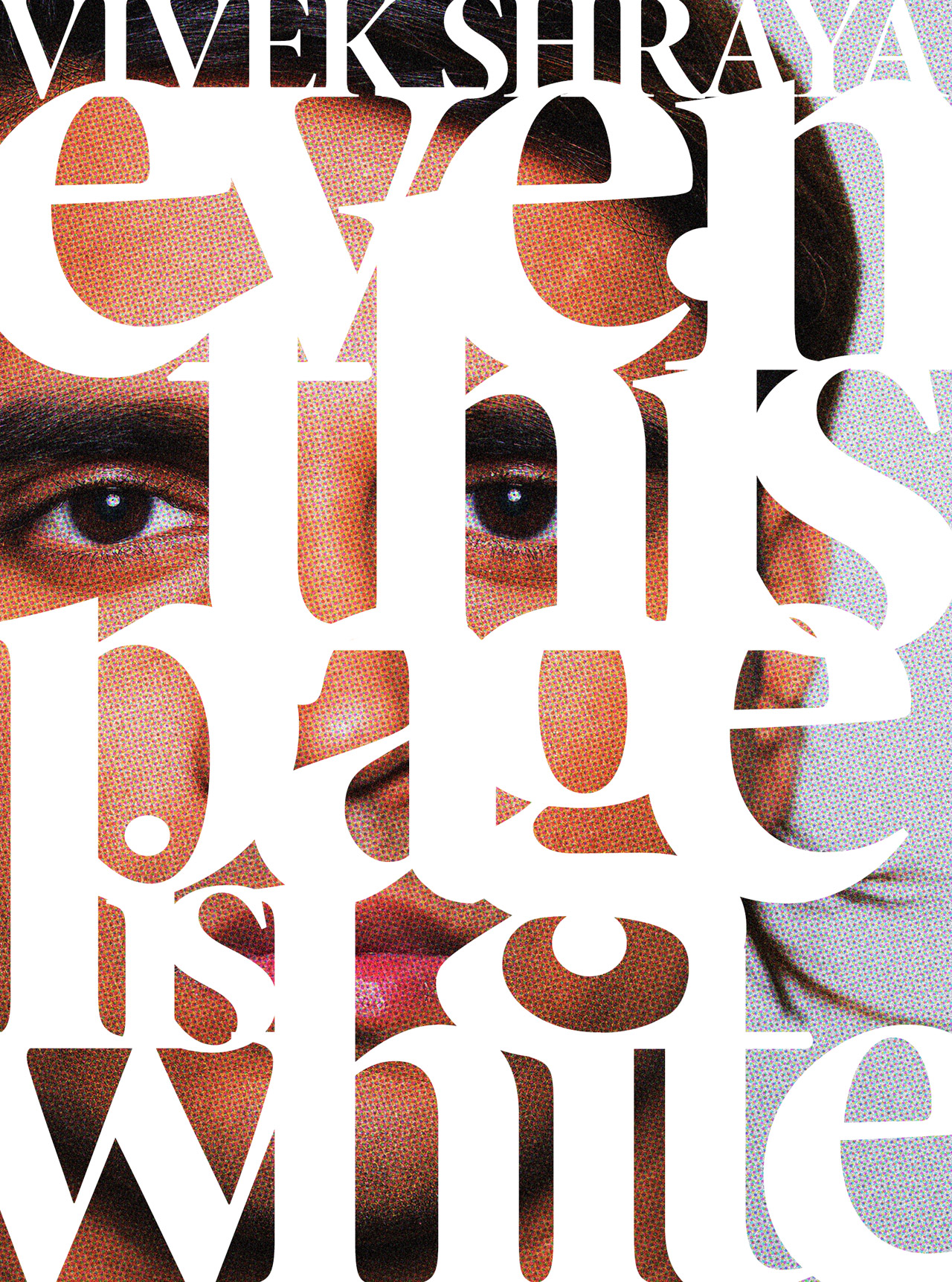

by Vivek Shraya

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016

Toronto-based multidisciplinary artist Vivek Shraya’s impressive body of work includes multiple albums, films, and books. Her debut novel, She of the Mountains, was among the Globe & Mail’s 100 best books of the year in 2014 and a Lambda Literary Award Finalist. Shraya, a trans person of colour, is currently receiving international attention for her photo essay “Trisha”, which pairs photos of her mother from the 1970s with recreations of the photos in which Shraya poses as her mother. The photos are punctuated by an evocative text that explores the oppression of women and what it means for Shraya, today, to “be feminine in a world that is intent on crushing femininity in any form.”

Toronto-based multidisciplinary artist Vivek Shraya’s impressive body of work includes multiple albums, films, and books. Her debut novel, She of the Mountains, was among the Globe & Mail’s 100 best books of the year in 2014 and a Lambda Literary Award Finalist. Shraya, a trans person of colour, is currently receiving international attention for her photo essay “Trisha”, which pairs photos of her mother from the 1970s with recreations of the photos in which Shraya poses as her mother. The photos are punctuated by an evocative text that explores the oppression of women and what it means for Shraya, today, to “be feminine in a world that is intent on crushing femininity in any form.”

With her debut poetry collection, even this page is white, Shraya applies her keen intelligence and awareness of positionality to white privilege and systemic racism. The book’s accessibility and attention to everyday racism will undoubtedly elicit comparisons to Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric. It is also possible to see connections between Shraya’s collection and Rankine’s brilliant Association of Writers and Writing Programs 2016 keynote, in which Rankine noted the work it takes to perpetuate racism and the privileging of whiteness. George Elliott Clarke, Canada’s Parliamentary Poet Laureate, has applauded even this page is white for demonstrating “why even a good white person—with a ‘golden heart’—‘can be racist.’” Shraya accomplishes this and more; she pushes beyond the simplistic binary of oppressor and other, beyond the notion that racism is anything other than commonplace. The result is an unflinching, timely, and necessary book.

The collection is divided into five sections—“white dreams”, “whitespeak”, “how to talk to a white person”, “the origins of skin”, and “brown dreams”. Shraya considers personal experiences alongside recent events such as #oscarssowhite, Miley Cyrus’ tone-policing of Nikki Minaj, and a white male poet’s use of the pseudonym yi-fen chou to achieve publication. By exploring the ways whiteness complicates her speaker’s desires and experiences, Shraya makes whiteness strange; it becomes noticed rather than invisible, pernicious rather than benign or normal. She nudges white readers to question, as poet Danez Smith puts it, “what makes you safe?”

In “indian”, a poem from the collection’s first section, we see the speaker’s mother lock the car doors after accidentally driving near a reserve; the speaker observes that it’s “strange to be indian and the sound of car locks / to be synonymous with indians.” (16) Only two pages later, within the same poem, we see the speaker lock her car doors against a black man; the moment is not sometime in her distant, excusable past, but “last year.” (18) Shraya’s willingness to acknowledge her own complicity in systems and legacies of oppression invites us to scrutinize our own roles in these systems.

As quickly as she acknowledges her complicity, Shraya insists that acknowledgment is not enough. What would it mean “to really honour no / show gratitude no / word for partaking in violence in progress” (17) she asks early in the collection, referring to the historical and ongoing oppression of indigenous peoples. Later, in “how to not disappoint you completely”, she wades through self-doubt before arriving at a place of vulnerability:

if i am learning should i know better

if i err am i failure

if i list my privileges am i accountable

if i ask these questions am i responsible

when i apologize will i be forgiven. (93)

Shraya’s masterful use of the page is striking. The majority of the collection’s lines occupy space near the pages’ outer and bottom margins. The white space that dominates the pages feels not neutral but purposeful, tangible, dense with meaning and history. The placement of Shraya’s lines can be read as a reminder that the ways we center and privilege whiteness have material consequences; marginalization is physical, white dominance is physical—in the speaker’s experiences, in society, and on the page.

Shraya is a generous poet; recognizing the discomfort that can accompany the acknowledgment of privilege, she offers us “conversation with white friends: / sara quin amber dawn rae spoon dannielle owens-reid”. (57) Here, Shraya and her friends explore the difficulties inherent in occupying a position of privilege while working to end the systemic oppression of groups to which one does not belong. Speaking from her experience as an ally responding to anti-black racism, Shraya notes that: “being an ally is ultimately / learning to be comfortable with being uncomfortable […] it’s more important that i use my voice and privilege, and / probably mess up along the way, than to do or say nothing.” (63) Musician and author Rae Spoon invites anyone uncomfortable with their unearned, unasked for privilege to make use of it: “the only way to support folks when you have more privilege is to give power away (which means space, money/resources, and time).” (65) Writer Amber Dawn reminds us that “allyship is gradual, delicate, challenging, and life-long work.” (66)

The final poem of this collection, “brown dreams”, is the only one centred on the page; the result is a literal centring of brown dreams. But even in “brown dreams”, whiteness is present; Shraya asks, “have you ever heard whiteness question its colour.” (107) This question sent me circling back to the first poem of the collection, “white dreams”, where the speaker, noting the whiteness of her pleasure, states “body you betray me / the only brown i make / for sewer.” (13) She then seeks courage from her core but finds that “even my bones / are white.” (13) This collection prompted me to wonder, what would whiteness have to mean for this speaker not to feel betrayed by it? What work do we need to do before writers like Shraya will be able to answer the questions she poses in “a dog named lavender”, a poem that considers the energy racialized people are required to expend in bearing the social burden of race: “what would i think of if i wasn’t thinking about this”, “what would i make if i wasn’t thinking about this”, “who could i be if i wasn’t thinking about this?” (53)

Kyla Jamieson lives and works on the unceded traditional territories of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations. She is an MFA candidate and has received awards from the BC Arts Council and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. She has written for Guts, Rabble, The Ubyssey, Feminisms.org, Canadian Elle, and more. Kyla was a Senior Editor at Shit Harper Did during the last election season and is the Poetry & Prose Editor of SAD Mag. She is currently participating in the Writing Studio at the Banff Centre.