Review by Francine Cunningham

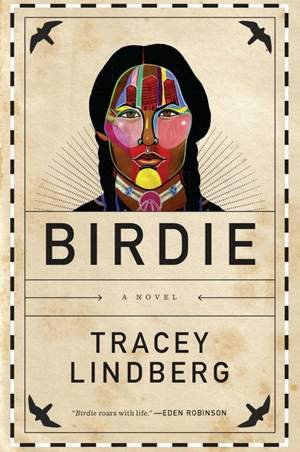

Birdie

by Tracey Lindberg

HarperCollins Canada, 2016

Birdie, written by first-time novelist Tracey Lindberg, citizen of the As’in’i’wa’chi Ni’yaw Nation Rocky Mountain Cree and hailing from the Kelly Lake Cree Nation, tells the story of Bernice Meetoos or “Birdie”, as she travels from Edmonton, Alberta to the small town of Gibsons, British Columbia, on the west coast of Canada. Inspired by her childhood obsession with actor Pat John who played Jessie, “a healthy, working Indian man” (7) on the TV show The Beachcombers, a Canadian comedy drama set in Gibsons, Birdie wants to see the place that “housed the actual Molly’s Reach.” (9) Once there, Bernice takes a job in a bakery, living in the room above. There she undergoes a profound transformation that leaves her unrecognizable from the scared and traumatized woman who first arrives.

Bernice is originally from the Little Loon First Nation in Northern Alberta, and is from birth both apart and a part of the community around her. Her family is non-status and is not allowed to live on the reserve. She spends most of her childhood hidden in her room under the stairs, living inside of her books and imagination as she listens to the sounds of her family all around her. As she gets older and leaves Little Loon, she finds that she can enter a dissociative state to become invisible and fly among her memories, listening to the voices that call to her. Which is both used as protection and a means to escape.

After Bernice receives news of her mother’s death from her cousin Skinny Freda, she embarks on weeks of self-destruction. She visits countless bars, drinking and sleeping with strangers. It is not long before she begins to notice her skin changing. Strange lists emerge written in a hand not her own. She spends more and more time out of her body flying through her memories. It is only when she finally lays down in her new bed and takes the time to let her spirit leave her body completely and travel back through memory and time to heal itself, does she finally confront some of the most traumatizing memories from her past, including the death of her mother, repeated sexual assault from the Uncles, and her life on the streets.

“A big Cree woman,” Lindberg uses Bernice’s weight as a symbol throughout the novel, as a literal protective shield. It’s a detail both the other characters and Bernice herself notices throughout. When asked about Bernice’s bodily transformation Lindberg states, “She gets skinny and then she starts getting well. Skinny is not well in this book…she comes into herself when she comes into her spirit, not when she comes into her body. She is sick in her skinniness, really, in the same way Pimatisewin (tree) is sick. She gets fed love as the tree gets fed love. She is better when fat with the love of women.” (264)

It took me a few pages to get into the flow of this book. The narrative style was outside of something I have read before. What was disconcerting in the beginning soon began to feel comfortable, and like Bernice, it let me float through the prose to the heart of the story, which is one of women, one of healing from trauma, and one of ceremony. The use of the Cree language made me feel at home in this story, as did her usage of words such as ‘thinkfeeling’ and ‘womanfamily.’ As well the way she formatted thoughts in short clipped sentences like, “A knowledge is born in her: that she has been to Then. And. She might not make it back. To Now. Little pieces of Now trickle in to her.” (227)

Lindberg addresses right from the start of the book that this story will not be a narrative that we have seen before. There will be no noble savage in this book. “I wonder how fascinated she’d be if she knew that I’d been fucked before I was eleven, Bernice thinks. That I smoked pot everyday; that I have read every Jackie Collins novel ever written—even the bad ones. Nope, that dying savage thing is what floats her boat.” (9) By addressing this in the first few pages Lindberg opens up the story and the reader to follow Bernice as a unique person, to forget what you think you know about Indigenous people and just experience this story about this woman.

As I was reading, I felt a kinship to Bernice and to this story. It flows in a way counter to what I have been taught writing to be. But it hit me in the chest with so much truth that I found myself crying throughout. I have never read a book that I felt connected me to a character I could actually relate to. On a sentence-by-sentence level this book spoke to me in a way no other book has. It felt right. I have never read a book where the words seemed written for me. Threaded throughout is an Indigenous point of view that shows itself both in the story and characters and in the actual words on the page—from the lip pointing to the bannock bums—it made me smile like I was in on the inside joke for once.

Bernice sits in the moment where spirit touches earth. From childhood she listened to the voice of the iskwewak or the Cree women as they whispered to her what to do and what not to do. The most powerful of these moments for me was when Bernice is praying in school and chooses to send her prayers directly to the creator and instead leaves out ‘all the Jesus and fear.’ She talks about listening to the rock people and having a special kinship with the Pimatisewin tree, a special tree in her community that signals health and life and which in part Bernice’s journey circles around. And not for a second did I believe her to have a mental illness. I believed that she did indeed speak and listen to these spirits. In any other book I would hasten to say these pages are filled with magic realism, but the words contained in this book are real. They feel like magic but I believe that this story of Birdie is true. I believe that if she were alive right now that yes, she could become invisible and melt into the past and present in the same moment. Blur the lines of what we consider possible.

This novel is itself a ceremony. From the first page the reader is invited to participate in the healing ceremony of Bernice. You only come to understand that as you move your way through the novel, like her cousin Skinny Freda, her aunt Val and Lola, you as reader are a participant, gathering lists and words, that culminate in a ceremony of healing for both Bernice and the Pimatisewin tree.

I could not zip through this novel in a few days like I normally do. I had to take my time with these words. I had to reread, set aside, and come back to, in order to fully absorb them. That, I think, is a gift that Lindberg has given readers. The way in which she repeats memories in different sequences can leave you feeling off balance and like you are part of the memory and it only reflects the emotional state of Bernice. This novel is structured less in a linear three-act structure and more in a circular structure that overlaps, which reminds me more of oral storytelling. In this way I feel that Lindberg is able to reflect both point of view and the type of story she is telling. Birdie is the novel that both Canada and myself have been waiting for.

Francine Cunningham is an Aboriginal writer, artist and educator from Calgary, Alberta currently residing in Vancouver, British Columbia. Francine has a Master of Fine Arts degree in Creative Writing from The University of British Columbia. Her work has appeared as part of the 2015 Active Fiction Project in Vancouver, in Hamilton Arts and Letters, The Puritan, The Quilliad, Echolocation Magazine, Kimiwan’zine, nineteenquestion.ca and The Ubyssey.