Interview by Nathaniel G. Moore

In her latest collection, Bicycle Thieves, Italian-Canadian poet, novelist, and essayist Mary di Michele examines the memories of her father’s life as an Italian in 1950s Montreal, and simultaneously reflects on what life is like after youth passes.

Mary di Michele is the author of a dozen books. Her novel, Tenor of Love, has been translated into Italian and Serbian. She immigrated to Toronto, Ontario with her family in 1955 and obtained an Honours BA in English Literature at the University of Toronto in 1972. Later, she completed an MA in English and Creative Writing at the University of Windsor in 1974. She is currently a professor at Concordia University in Montreal, Quebec where she teaches Creative Writing. In Bicycle Thieves, recently published by Toronto’s ECW Press, the poet presents Montreal as more than an identifier or a signal post. Throughout the collection, much like Leonard Cohen and Mordecai Richler’s use of one of Canada’s most iconic cities, di Michele makes Montreal her own musical style, chorus, refrain, and harmony

In “Ars Poetica,” di Michele delves into the divide between the written and the physical world with verve:

Writing, writing, and writhing—

I prefer not to, I prefer to

listen, yes, listen to the ocean

shushing the shore and more, Poetry’s

writing and erasing, writing and erasing

is all one solitary operation—

And that’s all I know about nothing.

I had the opportunity to interview the poet about her new collection, old movies, books, art, all things Montreal, and what inspires her.

Your latest poetry collection is in part an homage to neorealist Italian cinema. Can you discuss how this classic style of film inspired the collection, touching on some of your favourite films from the genre?

I was not so much inspired by the genre than by one particular film, Vittorio De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette, haunted by the gritty black and white, the desperate poverty depicted in it, the cruellest of compromises and cosmic ironies. Its drama or story is more Arthur Miller than Shakespeare as the character is never larger than life, though Antonio’s figure is physically so magnified on the screen. There are two poems in the book that reference the film: “De Sica’s Ladri di biciclette,” an ekphrastic, or ‘cinephrastic’ (to quote the Quill & Quire reviewer) that strongly turns, a Volta at the twelfth line, the speaker moving from description of the film to her remembered childhood; and “The Bicycle Thief,” a kind of ode/elegy for my father that tells the story of how he lost his bicycle. The image of the bicycle becomes an objective correlative, the vehicle for so much that is lost or stolen from our lives. It’s the image of the stolen bicycle that is for me the intersection of the public and personal: film art and post-war Italian history and a family story. I identify strongly with the child narrator in Lasse Hallström’s film, My Life as a Dog, trying to understand personal experience in the context of history, of the larger and collective story.

You mention turning 60 in a short poem referencing the author of Confessions of a Mask, Yukio Mishima. How did his work and other mediums from the past (art, literature, film) influence your new collection?

My reading is coeval with my experience in shaping this book and my life. I think “Life Sentences” most clearly demonstrates how this is so. As for Mishima, there’s masochism and an objectification of the body, of the self, an obsession with beauty in his writing that spoke to the wounded in me. “Everybody’s wounded” as Leonard Cohen sings, but not all of us in the same way. In the sixties, I read all Mishima’s books—well, all that had been translated at the time and were available in Canada: The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, his Confessions… are a few of the titles I remember reading. There’s spirituality mixed in with his eroticism, martyrdom as masochism or vice versa. I was a Catholic then, and there are elements of that in the lives of the saints. For him the iconographic image of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom was erotic. I often find deep correspondence and recognition in many gay male writers. How is it that they know how it feels to live in my skin? I am ostensibly a woman.

Was “Life Sentences” always going to go up to 100 verses? How did that poem evolve during the process of completing Bicycle Thieves? For me, the poem was a page-turner, something readers of poetry don’t often say, I would imagine, as one often prefers to read poetry slowly.

The first idea I had for the poem was to try to capture the arc of my life in a series of sentences—that was the constraint, each part would be composed of one sentence centered on an image, an event, an idea, a quotation, a reference, from my life or books and ideas influencing my thinking. I think we recall our experience in ‘spots of time,’ in fragments, not in a continuous narrative, so it seemed an appropriate form.

At first I thought I was going to write sixty-odd verses, to represent the years of my life. But publication and end of composition of the poem could be years apart so I decided on an arbitrary number, 100; it’s a nice round number, not that I expect to live to 100.

You called the poem a “page-turner”—that’s surprising! The structure is fragmented and so I would not expect a reader to feel the kind of narrative propulsion that causes page turning, the rush to see what happens next.

How do life and death as themes weave their way into Bicycle Thieves?

The collection is framed by poems that set up and close with this kind of weaving. The opening poem, “Scotopia” weaves the themes of life and death closely in its closing couplet: “we all bow to the darkness / we all turn in the light.” Scotopia is the scientific term for night vision, the ability to see in darkness; nocturnal animals have this ability and occasionally a poet gets flashes of it. The closing poem, “Somewhere I Never Travelled,” leaves you figuratively in a no-man’s-land between those two states, life and death, Canada and the US and vice versa.

Montreal is beautiful all year round. (Yes, even in winter.) What is your favourite season to live in?

Oh really, all year round? Winter is too long for my taste. I prefer the in-between, the temperate seasons. I particularly love May when everything blooms at once here including the maples with their acid green blossoms; the tiny flowers carpet the sidewalks.

What was it like working with Michael Holmes and misFit/ECW Press?

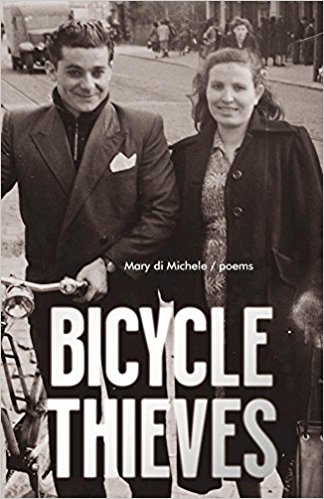

This is my second book with Michael and ECW. I have found Michael to be an incredibly supportive editor. He gets what I’m trying to do with a book. He has let me know within a month of submitting whether he would publish the manuscript or not, and publication was slotted within a year of submitting. His enthusiasm about Bicycle Thieves when I sent it to him put me over the top. I think the design people at ECW did an amazing job on the book. I gave them a family photo to work with for the cover and asked them to make it look like a still from an Italian neorealist film. They went all the way with the idea, including the titles and fonts in the book. And I laughed with surprise and delight when I first saw the FINE at the end of the book.

Nathaniel G. Moore is a publicist and writer living on the Sunshine Coast.