Reviews by Elee Kraljii Gardiner

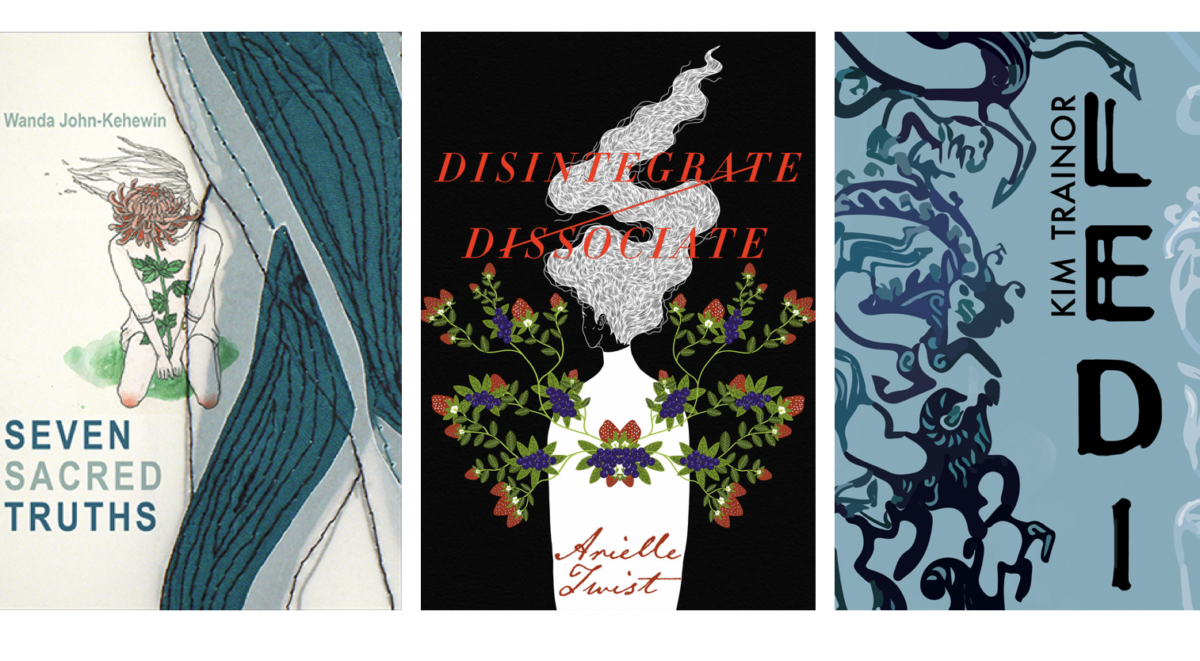

Seven Sacred Truths by Wanda John-Kehewin, Talonbooks, 2019

Disintegrate/Dissociate by Arielle Twist, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

Ledi by Kim Trainor, Book*hug Press, 2018

A life is not a linear collection of events, but perhaps a palimpsest, a collage, or a nest woven of influences and occurrences and beliefs. These three books contemplate life as it interacts with death and difficulty, using idiosyncratic modalities. John-Kehewin blends narrative, prayer and reflection into an invitation to converse as if we are trusted friends sharing coffee. Twist brings the fire, the rant and the loving fury. And Trainor, puzzling the philosophical loneliness so many of us feel after suicide, goes back in time with science as her safety net. Poetry allows us to construct meaning not only from content but from form, coding the shapes of lines as well as the delivery. Here are three voices at three different stages of life in three different circumstances seeking the same end: peace.

Seven Sacred Truths by Wanda John-Kehewin, Talonbooks, 2019

This second collection from Vancouver-based Cree/Métis poet Wanda John-Kehewin returns to a place of witness that psychologically complements her debut, In the Dog House (Talonbooks, 2013). That collection featured discrete poems, while this one laces prose, experimental poems, testimony, acrostic, prayer, poems of witness, essay, memoir and recollection. In terms of grappling with the who am Iand what are my concerns, questions emerging authors tend to answer in their first books, Seven Sacred Truths collects the author’s learning and places it right on the page, beautifully, confidently, and with the type of stare-you-in-the-face storytelling that can only be accomplished with the wisdom of self-awareness. These texts do not dress up or pretend. What is more sacred than a woman knowing herself, accepting herself and moving forward into a place of self-determination?

One thread of poems about family displacement, abuse and residential schools manipulates typography to capitalize the letters of certain words as they appear individually in the poem; “mommy” is one used a few times, another “dad,” and yet another, “no.” At first the atypical font looked wacky and I had trouble reading, getting frustrated, tempted to skip through the poem.

i wOuld have washed

YOur hair with

hOney, leMOn,

and cedar water.

—MOMMY i wOuld have.

But as I recognized the code and saw how the absence of a mother, or rather, her skewed presence, is woven through every moment of John-Kehewin’s life, I stopped fighting. I slowed down to work through the lines because I owed it to the narrative. Reading it was hard, both visually and emotionally. Why should my reading of a troubling, unjust story be fast, smooth and easy? The author’s method was deeply affecting, a meta-gesture towards the pain the author recalls in her clear, retrospective pieces.

In her essay, “An ‘Indian’ Never Dies Peacefully,” she relates the circumstances of several suicides around her as a child. It’s an accumulation that is unbearable precisely because of the balance of prose, which itself is very simple. John-Kehewin draws the connections between colonialism’s cultural and physical genocides and her reasons for writing this book with frankness:

I can still hear the grass dancing in the wind through the open window and feel the slight coolness of the breeze that entered our dark basement suite. He had hung himself with a belt in a white closet from a solid wood dowel. I remember those dowels and how thick and strong things were made in the old days, I know because I would hang from the same dowel Jimmy would eventually see as a solution to his pain and sadness.

Seven Sacred Truths is a prayer, literally. It opens with prose poem prayers to the Creator, the Universe and Ancestors. These meditations are method for surviving and moving onwards to repair epigenetic ruptures with the next generation. This type of healing is never complete, she warns, but it can become a way of life. Seven Sacred Truths uses poetry as just one of its vehicles for moving forward. John-Kehewin offers her own experience as another, reminding the reader that each person has their own truth to reconcile.

Disintegrate/Dissociate by Arielle Twist, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019

In Arielle Twist’s debut poetry collection she asks rhetorical questions of herself, the city, the prairie, cis white men, and others. This is a book of breakings in the sense of ruptures with the past, both those imposed by this awful world and those designed by the author in order to survive. The snappings, crackings, chokings and burnings manifest in questions such as “Why do I have a body like mine?” in “Born in Mourning”, searing through the pages as Twist writes toward reconstruction, a rebuilding of self.

The night our kokum died,

my mother cried out in

another language.

I hear her break,

the cracking of burning wood,

like it was my own bones

between walls of mud and dust,

the structure, on fire.

—Prelude

Twist’s poems are packed with challenges skewering the guy who left, the guy who stayed and, most poignantly and effectively, the self. I hear Plath in these lines:

They always told me this body is mine,

that autonomy is key

breakdown, undone

I can destroy it freely

so, I will.

—Vacant

Ferocious desire, sex, yearning, complicated rejection and acceptance flood these poems, giving us a window into one woman’s experience of existing in her trans body. Poems run from conversational to crisp couplets to pieces verging on rant and slam as they ask how we might mourn what we never wanted and how we might live within a series of structures built to wreck us. “Who will save you now that your homelands/hate the holiest parts of you?” she asks in “Who Will Save You Now?”And yet Twist, whose poetic voice is fierce and assertive, allows the reader into the unknowing with her.

There is so much

I don’t know

about the potholes and prairies

inhabiting parts of my body

—Bear

Those lines destroyed me. It wasn’t only the subtle locating of urban overuse, but the mention of displacement, the land of the body colonized in both the political and personal sense, that choked me up. Twists’ ability to gesture towards complication with such directness is a gift, as these lines from “Under Uprooted Trees” demonstrate:

A husk of faux

masculinity,

toxicity,

this shell of

a man who

never existed.

—Under Uprooted Trees

For any readers struggling to integrate their own histories or politics, Twist may have titled her work disintegrate/dissociate, but she has perspective beyond her years.

Auntie, be proud

because I know there is learning to do

and I am patient, I promise

there is learning to do and I will try to unlearn

with you.

—Iskwêw

Ledi by Kim Trainor, Book*hug Press, 2018

Vancouver author Kim Trainor returns to poetry with a second book after 2015’s Karyotype (Brick Books), this time yoking the discovery of an Iron Age woman buried in the Siberian steppe with the disappearance of the author’s ex-lover who died from suicide. The structure of the sequence of poems, which consist of prose lines and almost notebook- or journalist-style notations, is one of pulling away from a centre, crossing two deaths on a parallel track as we begin to understand the situation. The poems explore scientists’ work reconstructing the body/life of Ledi, the Pazyryk woman whose body was uncovered largely intact, tattoos visible on her shoulder, while in the present day the author reconstructs and repairs from the death of her friend.

The positioning of the two situations is interesting: one, an appearance of someone we know little about; the other, the disappearance of a former intimate. I’m not sure how, but Trainor has managed to flesh out Ledi enough for her to become a mesmerizing character in the book, almost a contemporary we can relate to via her height, her long fingers, tattoos, and tunic.

One of the main through lines is the evocative descriptions of the wild grasses and flowers around the burial site, which Trainor repeats and restages in order to collapse the distance between Ledi’s hollowed cavity and Trainor’s own emptiness. The process of death is natural here, and so is the corpse’s natural overtaking with vegetation, but what a stark contrast to the absence of witness to her lover’s premature death.

7 May. Of all the accounts of her I am most touched by the description of her hollowed body filled with earth and thin roots of grasses.

15 May. I have been thinking of what it means to be alone. He once told me that when he talked to people they didn’t really hear him. His words passed through their bodies like subatomic particles without touching them, leaving no trace at all.

17 May. It has become instinct for me now to turn away from other people, to climb more deeply into my body, as if it were a cave, and crouch here, watching from a safe distance.

This is a book of longing and grieving amidst questions that may never be answered.

I look everywhere for you. In tins and shoeboxes.

There are so many things I cannot find.

A reel-to-reel with your name on the label

gummed to its centre, and a question mark.

Is it you?

…

I can’t recall your face, your voice.

…

4 June. As she emerged from the ice, toward the very end,

they used their fingers to work at the fabric on her body, to

ease her left arm out without tearing off her skin.

…

So I work your body in memory.

It is devotional labour, both the speaker’s memorializing of her lover and this unearthing of Ledi that is done by nameless archaeologists. There is no guarantee any of it will work. As the scientists in the field repeat the act of pouring cupfuls of melted ice water over her trapped body the very act of rescue does damage.

13 June. Her decay began the moment her skin came into

contact with human hands and sunlight, with tiny micro-

organisms in the warmed lake water used to melt the ice.

This is what grief feels like, isn’t it? The repetition, the daily visits with damage, the uselessness of the task. Trainor recreates the endless small efforts to make sense of something ineffable and unavoidable in its mystery. In the end, it is only the slow work of the wild grasses and flowers that persists where any body could, did, or might have lain.

Elee Kraljii Gardiner is the author of the poetry books Trauma Head (Anvil Press, 2018), a chapbook of the same name (Otter Press, 2017), serpentine loop (Anvil Press, 2016), and the anthologies Against Death: 35 Essays on Living (Anvil Press, 2019) and V6A: Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2012). eleekg.com