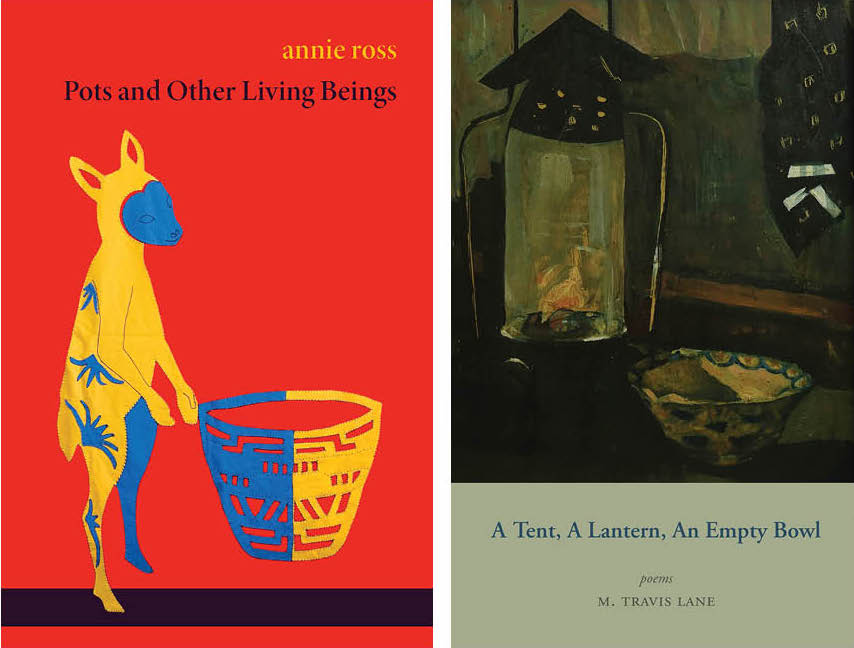

Pots and Other Living Beings

annie ross

Talonbooks, 2019

A Tent, A Lantern, An Empty Bowl

M. Travis Lane

Palimpsest Press, 2019

Review by Kim Trainor

With the advent of SARS-CoV-2, for many of us there has been a contraction of the world and a turn towards the small; comfort is found in ordinary everyday objects—a cup of coffee, a notebook, a pencil, the feel of earth in your hands as you transplant tomato seedlings.

So, I was drawn to the titles of these two poetry collections by annie ross and M. Travis Lane for the attention each poet places on such unassuming, necessary objects: a pot, a tent, a lantern, an empty bowl. Their titles also remind me of Ursula Le Guin’s essay, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” in which she argues that the spear was not the first important human tool; rather, it was the container, whether pouch or basket, for its ability to carry things, to gather seeds and fruits, a tool everyday and utterly necessary. Le Guin extends this idea of the container to narrative––the thread that is woven to catch a story––but it can equally be applied to a poem. Both ross and Lane employ imagery of essential domestic objects, as well as stitching and weaving, in their poems. Lane notes the absence of war in her own poetry, while ross obsessively details the stark presence of nuclear colonization and the military industrial complex on Indigenous lands in her collection.

M Travis Lane, in her 18th book of poetry, subtitles the first section “Quilt” and begins with this image: “Imagine a quilt of water, every square / stitched on the page of afternoon”:

the pin-pricked surfaces of snow

beneath red, thawing twigs—

ice-lensed, the blue-brown water

fussing below a bridge—

the mud-opaque of ocean waves

against which a crochet of foam

reiterates—

(“Imagine a Quilt of Water”)

The poem is threaded with references to crochet, embroidery, scraps of colour selected from the natural world and stitched together by stanza break, hyphenated words, dashes. The second section of the collection, “Banner” similarly begins with these quiet, beautiful stanzas:

I knit a banner with gardening twine,

a chicken bone for ‘ivory,’

old buttons, twigs, dry leaves.

My busywork records no wars,

just ordinary weather: death,

disease, disheartenings.

(“Banner”)

Here again, we see the poet’s attention focus on domestic artefacts and practices: knitting, gardening, buttons, twigs, chicken bones. Here is one of the great strengths of poetry: its ability to carry such small things in a beautiful container of words, to celebrate the minutiae of everyday life.

annie ross’ first collection of poetry, wonderfully titled Pots and Other Living Beings, also works with functional domestic objects and tropes of weaving and stitching. Her book reads like a travel journal or a field notebook; the book itself is a long sequence of triads consisting of two photographs and a poem that speaks to them—again, a form of stitching or patchwork. Within each triad she documents several road trips taken through the southern United States while collecting testimonio on the nuclear colonization of Indigenous lands: “testimonio/testimony work is first-person, experience-based, recalling of events from individuals at the front lines of harms and injustices from lawless powerful groups and state-sponsored actors,” she says in a recent interview with Rob Taylor. Most of the poems contain her own observations, interwoven with observations made by these witnesses. For example, “the evolution of Fruit” places two images together: a tree with bare branches against the sky, and below, shelves stocked with tins and plastic cups of processed fruit: Oregon Purple Plums, Dole, Mott’s Mango-Peach. The adjacent poem reads:

Gooseberry, Kumquat

pretty labels, metal cans, fluorescent lights

is this what has become of us

Oregon Grape, Wild Cherry, pear

Tree orchards at hanford, washington, cut down to make

enriched uranium

nuclear bombs

someone said, plutonium pits look exactly like

a sliced-open Avocado

(“the evolution of Fruit”)

This is one of her most technically precise poems, with its specificity of language and the striking comparison of plutonium pits to a sliced-open Avocado. Further work is done with capitalization or its absence: plants and earth, water, are all capitalized, while human artefacts and places are made small. There is perhaps an overly binary determinism here: domestic activities are good while science and technology are equated solely with devastation:

darn a sock

sew a hem

crochet a pot scrubber from a ballerina skirt

needles clacking

tie a knot onto a knot

in a perfect row

Teller wanted to know everything

by breaking it all apart

atoms, hydrogen,

Pikinni Atoll

(“knit”)

She observes that the Micronesian island’s name, which nuclear history knows as the “Bikini Atoll,” was in fact based on a mishearing by 19th century German colonisers. Nuclear testing on Indigenous territories has taken place on a global scale and Teller has been called the father of the hydrogen bomb. Although this is another of ross’s strongest poems for its imagery and rhythm, I want to resist the depiction of science as something which destroys by taking apart while the domestic (darning, sewing, crocheting) is something that joins: “some people know more/by knitting it all together/binding, sewing, making order […] keep it all together/Gather, Plant, Sow” (“knit”). Science can offer other ways of seeing and knowing, different, not always destructive and bad. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work on moss is an excellent example of this; she offers the precision of scientific terms (sporophyte, gametophyte, pleurocarp) to allow us to see the world anew: “finding the words is another step in learning to see.” (Gathering Moss). Yet I also want to agree with ross’s assertion because it speaks to the specific history of the land she travels through, where scientists first unleashed the destructive power of matter. The perspective offered in “knit” accords with her research trips as well as her personal experience (as described in the previously mentioned interview) and surely rings true for her and for the histories she transcribes.

The accompanying photographs of mannequins, abandoned signs, military surplus, half-eaten meals in diners, and spare Mojave desert, create an eerie and despairing tone of such unnecessary loss and devastation caused by brutal indifference. In part, the black and white images contribute to this; apparently the originals are in colour, which might impart a different tone, but colour prints would have been too expensive. As they appear here, the overall bleak tenor is in contrast to the title, which honours domestic objects as living beings. So too does the beautiful stitched image of a creature standing on its hind legs next to a pot on the cover—ross’s own art, an applique on a red and black blanket. These tensions inform the book as a whole.

Kim Trainor is the granddaughter of an Irish banjo player and a Polish faller who worked in the logging camps around Port Alberni in the 1930s. Her second book, Ledi, a finalist for the 2019 Raymond Souster Award, describes the excavation of an Iron Age horsewoman’s grave in the steppes of Siberia. Her next book, Bluegrass, will appear with Icehouse Press (Gooselane Editions) in 2022.