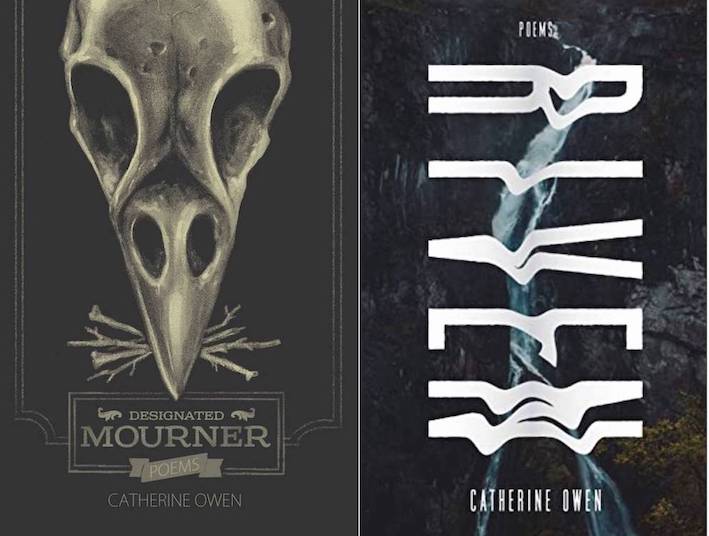

Designated Mourner

Catherine Owen

ECW Press, 2014

Riven

Catherine Owen

ECW Press, 2020

Review by Kim Trainor

Last night I went down to the river, the Fraser slipping through Delta’s fingers, past Westham Island, mud-green flow of water tipped silver out to sea. A warm August evening, swallows like black cinders at dusk, peaceful. But the river is fickle. When I was nineteen, after my partner had tried to take his life, been hospitalized, released, still wanted only to die, his mother and I took him to the Fraser to sit among the reeds and the trill of blackbirds, to have a picnic; she thought it might help him heal. I remember it as a sunlit, crisp day, but everything felt flat and two-dimensional, tasting like ashes on the tongue. We were afraid. I felt that we had to hold onto him but he wouldn’t let us; he was already a shade, slipping away.

These books by Catherine Owen are about this kind of loss––the hard work of loving and grieving and letting go. Designated Mourner is raw, transcribing the year following the sudden death of Owen’s partner from an overdose. Riven charts the subsequent year, the Fraser River as a body that is worked and reworked: memory, language, the body of the dead. These poems will speak to anyone who has experienced abrupt, traumatic loss of someone who died too young.

My copy of Designated Mourner is warped by water, the cover ashen, from my carrying it like a talisman in my backpack, between notebooks, leaving it out spine down in the sun. The first epigraph points to the title, “Much more often than not, women were the designated mourner,” (Katherine Ashenburg).

The book opens with “The Lung Poem:”

The poem breathes for you some days

It’s okay

…

Some mornings

The poem is a lung

The central metaphor of the poem as lung reminds us of the elegiac function of much lyrical poetry: the words point elsewhere, to what once lived, to what is gone, but each time we speak its words, we breathe once more for the lost. It reminds us also of the recuperative and resilient nature of poetry: it helps us to breathe, to stay with the living: “The poem breathes for you some days.” The alternating long and short lines suggest the quick intake of air and long outward breath, like a pulse. Poem as lung metamorphosizes into poppy, “opening like a soft heart in the sun.” Even as the poem acknowledges loss, it also denies it; the body is gone, but it is here in the poem, as heart, as lung. He is still here.

“The Lung Poem” is followed by seasons of mourning. Free verse is interspersed with formal structures which channel grief and work through the anger that is also present, as in “The Crackhead’s Palindrome,” which begins, “It comes right down to this. Just one more hit / and he will be cured of the need / for this frenzy in the dark, this scrounging…” and ends, “All for this frenzy in the dark, this scrounging / to be cured of the need. / It comes right down to this. Just one more hit.” This particular formal structure recapitulates the trapped, circular nature of addiction. While I suspect the formal structures are important grief work for the poet, I am less compelled by this technically perfect but rote work—it helps the day to go, the memory to be held at bay. The most compelling poems for me are the ones where Owen remembers some small detail of her partner, which complement the darker poems in which she remembers their corporeal lives, her lover’s body—even in death he has an erotic charge.

“Autopsy” and “What I did with the remains” explore the erotics of death. In “Autopsy,” the poet describes seeing her lover’s body in the morgue: “This is how real he was: he would have loved / to have watched his own chest / sawed open, rib cage split, his dead heart bared, / then cut to reveal the clot that killed him.” It concludes, “…I try not to let it / pain me, the butchery of what I once stroked / & sucked & signed the papers for its burning.”

There is no attempt to shield the dead or to deny our materiality; even as he has become a body, subjected to “butchery,” she recalls this is the same body, the same matter, she once “stroked / & sucked” and now must sign “the papers for its burning.”

In “What I did with the remains,” Owen describes walking into the forest with his ashes but finding herself unable to scatter them. Just as she describes his body sawed open and heart exposed in the morgue, here she describes her own body “blanched” as if in sympathetic death; recalls the conjunction of their bodies in love, once “locked into each other,” now smears “the slight sear of ashes / on face, breasts, pubis, become blanched.” They are conjoined once more, the grit of his bones, salt of her tears.

The poems in Designated Mourner feel honest and raw.

Riven finds the poet a year later, although there is some overlap here, as the final section of Designated Mourner includes poems written “A year subsequent & after,” spanning the years 2011 to 2012. Riven finds the poet relocated to the Fraser River, now living with a new partner, but seemingly less in love with him and contemplates leaving him. She is split—or riven, as the book’s title suggests—addressing both a “you” in the present, and the ghostly lover of Designated Mourner. Because time has passed, the poems in Riven are less raw, more like taut, silvered scar tissue analogous to the river itself, apparently seamless but liable to split or break open at times. The poet still does grief work but now looks outward, describing the industrial features and colonial past of this working river, its toxins and pollutants, its log booms.

The Fraser is a constant presence, evoking Lethe and Styx, the body of the ghostly lover, a body of language, all pointed to in the collection’s opening numbered poem, “Thirty-Six Sentences on the Fraser River that Could Serve as a Very Small Nest.” Sentence 4 perhaps perfectly encapsulates the movement of the book and the nature of grief: “4. The river is like your death; it just keeps moving away from me.”

Difficult today, the tears – and I see the river through them – sun swoons in

the window,

slides a shape down the picture of his face on the dresser – long, honeyed

rectangle of memory –

I look at it – awhile – doesn’t stop – grief – just, grieving sinks inward,

becomes moments more

subdued, quiet…

The central focus of this collection is a beautiful suite of aubades; these are dawn songs but also songs of separation, poems written by a lover as they leave their beloved after a night spent together. There are several kinds of leaving considered here. She considers abandoning the current relationship; in “Sundays in the frozen construction site,” she writes “—all week long I wonder // if I should leave you, because I say love and not in.” In each return to the river she addresses the ghost of Designated Mourner, still mourns his leaving her, as in “Difficult today, the tears—and I see the river”:

She considers how the dead leave us, and how we leave them. Similarly, the desolate industrial sites of the working Fraser are being developed and lost. The birds migrate, the river is in constant flux and always flows away: “the starlings in the muddy field alight and there is the / impartial in this; they pick among the river’s winters // ; they move on” (“Every day I go to find you & every”).

In “The Last Aubade,” there is a turning point; the ghostly lover of her past is absent, some peace has been found. She writes:

—but I would rather this now than a story I never

really planned to tell anyway—you understand—and everything—

even the crows this morning—are silver—their wings—as

they twist backwards into the gleam—catching

the days we have left together—silver you could say as scars, or age,

or ashes—silver as what holds everything this morning

—after all we’ve been through—over the always-silver river.

Owen has recorded this poem and posted it to her YouTube channel. I encourage you to listen to her speak it over the images of the “always-silver river.”

Kim Trainor is the granddaughter of an Irish banjo player and a Polish faller who worked in the logging camps around Port Alberni in the 1930s. Her second book, Ledi, a finalist for the 2019 Raymond Souster Award, describes the excavation of an Iron Age horsewoman’s grave in the steppes of Siberia. Her next book, Bluegrass, will appear with Icehouse Press (Gooselane Editions) in 2022. She teaches in the English Department at Douglas College and lives in Vancouver, unceded homelands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations.