Interview by Uche Umezurike

KB’s poetry shimmers with a playfulness that veils the scars and struggles of a poet who refuses to be defined by the politics of propriety and respectability. Each poem raises a fist against gender binary, emphasizes the viability of queerness, of blackness, and articulates KB’s own modes of identity and intimacy.

Uche Umezurike: Congrats on winning a PEN America 2021 Emerging Voices Fellowship. What does it mean for you to have such an award, KB? Could you describe what this moment represents for your poetry?

KB Brookins: This is huge to me for many reasons. First being this is the longest-term investment that anyone’s ever made in my poetry—the PEN fellowship is five months. Second, I was able to pay a bill for my mother and spot a bill for a friend with this money; I’ve never been in the position to do that, so I’m feeling blessed upon blessed. Third, I wasn’t able to finish an MFA I started years ago, and since then, I feel like I’ve been subconsciously trying to prove that I can do the poetry thing without that paper and that a place in poetry exists for me, even if I have to break through some cemented doors to get to it, to get to another version of myself. I’m glad PEN saw that grit in me, and I’m ecstatic to have their support as I embark on birthing my full-length collection in the coming months.

UU: How to Identify Yourself with a Wound explores themes of queerness, mother-daughter relationships, self-acceptance, pleasure, agony, mourning, and alienation. What did you find most challenging about writing the book?

KBB: Honestly, the most challenging aspect of it is believing that I was the person that needed to write it. Because all these poems were written in the two years after I decided to leave my MFA, I was petrified of messing up, of digging deeper into myself as a poet, as a person, as a gender. As I was writing this book, I was transforming in many ways, and it took me nights without sleep to be confident enough to tell the truth (and share it with others). I’m grateful to Kallisto Gaia for seeing something in me.

UU: “Self-portrait as pangea” works as a kind of erasure poem that examines the family, femininity, and agency. The speaker refuses to fit “the simulation.” How has poetry helped you to deal with questions about identity?

KBB: I’d say less femininity and more the function of gender in our society as a whole. One of the reasons why I write poetry is to learn about myself. There’s something about letting my hand move and doing something with the nonsensical word associations that my psyche comes up with that’s magical for me. In this poem, I was sorting through some Gender Feelings, and in that process, I really thought of myself as continents splitting, because I’m rejecting womanhood and manhood from both sides of America (and I still do). I’d say that I decided to share this poem with others because I want to give folks access to new feelings. Yeah.

UU: There are references to songs by Ariana Grande, Frank Ocean, and Kendrick Lamar in your poetry. What is the relationship between music and poetry for you?

KBB: Love this question! Before I had poetry, I was a kid looking out of the backseat window on drives from my mama’s job to my granny’s house, imagining worlds with the backdrop of music in my ears. Music has been such a vehicle in my life for so long that it makes sense for it to seep into the poetry. Oftentimes, when I’m crafting a poem, I have a song stuck in my head that I’ve been playing a lot that week, and I’ve actually made a list of songs I had on repeat while writing How To Identify Yourself With a Wound, which you can listen to here.

UU: “I’ll Miss the Women’s Restroom” is painful and almost elegiac, at least for me. It touches on vulnerability, (hyper)visibility, and violence. The restroom is portrayed as a site of imminent violence for nonbinary people. What has drawn you to this space?

KBB: Literal real-life events that have happened to me, really. It’s violence on both sides of the spectrum—women’s rooms and men’s rooms—that I’ve experienced, and the big difference is how the violence is portrayed, usually in words from the women’s room and physical violence from the men’s room. In my nine-to-five life, I advocate for genderless/all-gender, accessible restrooms for this reason. Like, I just wanna pee man, and people feel really bothered by me being around in those spaces for some reason. I wrote this poem also after getting top surgery, and because I’ve been perceived as a man and a woman depending on the audience at hand, it makes for interesting stuff going on. So, I wrote about it.

UU: In “Upon hearing the news about,” the speaker reflects on antiblackness and the police killing of African Americans in the United States. A sense of powerlessness pervades the poem. In “Transplant,” the speaker asks, “Can one suffocate from overwhelming whiteness?” Could you say a bit about these poems?

KBB: For sure! For me, the former poem was an exploration of what a typical day looks like when something violent is in the media, and I tried to depict the tension between being desensitized to it but still very much affected by it. It’s a violence that the world still runs when Black people are killed by police in this country. And it takes a toll when one name turns into the other, protests erupt, and it’s the minimal, limited progress that leads to the same thing happening in a few weeks again. So, there’s that poem, and the latter is a lot about living in Austin, Texas and seeing gentrification so in your face yet silent. That’s another erasing of Blackness that happens that I’m constantly confronting here.

UU: There are four variations of the title poem “How to Identify Yourself with a Wound.” I’m curious as to how you came about this phrase, “it’s best to identify yourself with a wound.”

KBB: I was actually at a poetry reading and heard ire’ne lara silva say “when you identify yourself with a wound” in relation to identity, and I kind of started to go on a deep dive on the internet on this phrasing. It was fascinating to me. Then I turned a bit inward like, “Well damn, this white supremacist state would like to think my Blackness, queerness, transness, nonconforming nature is a wound, huh?!” Then I started to look back over my life and arrive at these moments of woundedness. And then the book idea further emerged.

UU: Finally, is there something you would like to leave with readers?

KBB: I’m so happy that this chapbook is gonna be available to be held in people’s hands, hearts, Kindles, and earlobes (stay tuned) very soon, and if you’re interested at all in my work after reading this, you can follow me @earthtokb on Instagram or Twitter. I’m also on Patreon with exclusive teaching and writing content, plus zines, prompts, and more. Thank you!

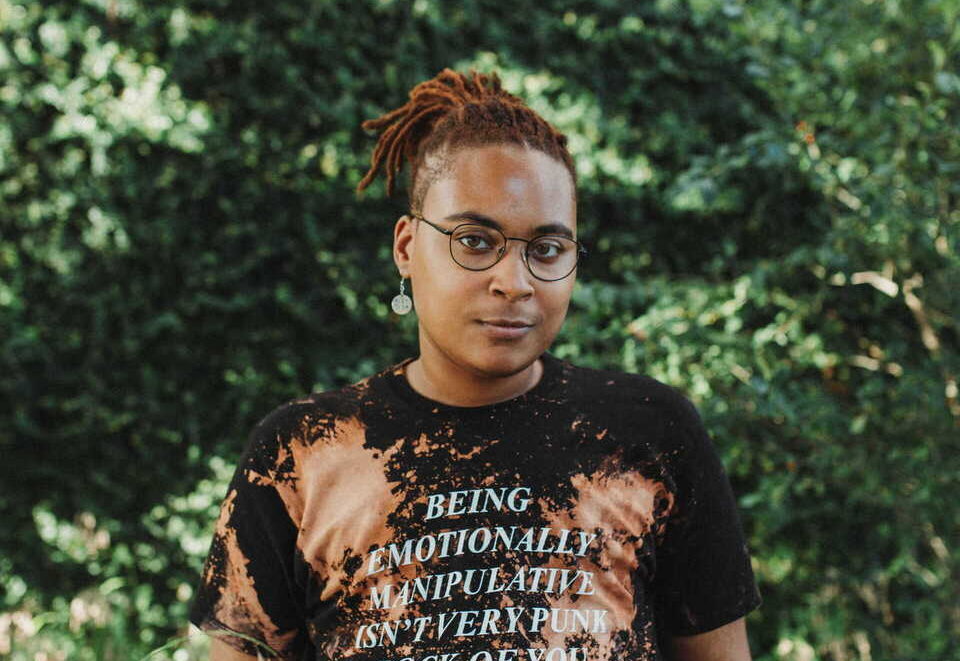

KB is an award-winning Black queer nonbinary poet, educator, and student affairs professional. They are the author of the chapbook HOW TO IDENTIFY YOURSELF WITH A WOUND (Kallisto Gaia Press, 2022), winner of the 2020 Saguaro Poetry Prize. They split their time between being Program Coordinator for the Gender and Sexuality Center at the University of Texas at Austin, Founding Executive Director of Interfaces, Co-Founder/President of Embrace Austin, and educator in various settings. Most recently, they were named an African American Leadership Institute – Austin fellow, Equality Texas fellow, and a 2021 PEN America Emerging Voices fellow. Their motivating force is justice for all marginalized people.

Uche Peter Umezurike holds a PhD from the English and Film Studies department of the University of Alberta, Canada, where he is an Assistant Lecturer. An alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), he is a co-editor of Wreaths for a Wayfarers, an anthology of poems.