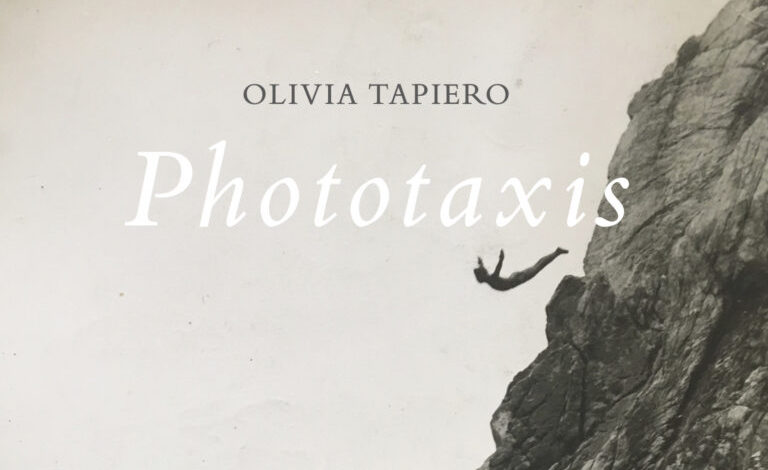

Phototaxis

Olivia Tapiero

Translated by Kit Schluter

Nightboat Books, 2021

Review by Marisa Grizenko

Olivia Tapiero’s Phototaxis, translated from French by Kit Schluter, opens in a world we can recognize. The incomprehensible has happened, and happened again, yet people continue living their lives. Théo Schultz, a pianist, prepares for his comeback after having disappeared from the world of classical music for some time. He poses for promotional photographs and rehearses. Meanwhile, sandstorms rage through the city, rendering the air unbreathable and blanketing everything in dust. The streets are inexplicably covered in a layer of meat, a “steaming flood of animal mash.” Lard hangs from the trees. In the river lie the bodies of murdered dissidents, on the coastline “beached whales bloated with methane explode all over the closing shore shops.” That there have been radically destabilizing events in the political and social spheres is gestured to more than explained. There is mention of resistance fighters, communes, and a vast state-sponsored surveillance network, but Théo must prepare for his concert: “The parade marches on.”

He does so with great resignation, and only because of the obligations of his contract. In fact, he’s lost his love of music. “I squandered music,” he thinks. “Trampled it, by believing in my mastery.” Théo’s all-consuming desire to be admired, his craven participation in the publicity machine, and his fears about his own mediocrity have deadened his life’s passion. Without the consolations of music, he increasingly spends his time ruminating on “disaster, ruins swallowed up by plants, forest fires, floods, industrial chemical explosions, snuff films, and above all, infinitely, the image of the falling man.” The latter refers to a man photographed falling from an office tower in the city, but Tapiero links him with others called by that name: the first person to be captured falling from the Eiffel Tower, the man falling from one of the Twin Towers on 9/11, and later Théo himself.

Before that, though, Théo simply dreads the future, his face plastered on posters all over town. A friend named Narr drops by, seeking news of Zev, the beautiful revolutionary known for hosting sexual and political gatherings. He’s missing, likely (his friends think) to plan a large-scale attack. If Théo is a failed artist and Zev a rebel desperately trying to remake the world, then Narr is a nihilist, wholly rejecting society and her place within it. An immigrant from “the colony,” she is a figure of dispossession, with no real sense of home—in part because of her wariness of belonging to a group. “Could I not simply arrive from nowhere, free and bloodless?” she asks. She’s also disenchanted by narratives of integration, citing her “foreign skin” as a permanent marker of her difference in her new country.

Composed of six short sections in which different people speak—including Narr, her mother, a sneering conductor, and Théo—the book is a beguiling collage of textures, voices, and moods. We move from moments of dark humour, to expressions of erotic longing, to cries of existential despair. Often, the language is opaque, the characters speaking to one another in grandiloquent phrases, the descriptive sentences failing, perhaps purposefully, to meaningfully describe anything. “Nostalgic hymns console the abulic, their palliative accessibility subject to a castrating maintenance, the delimination of the accessibility of desires, angers, hopes, and maladies,” the third-person narrator states at one point. In other places, the words halt the reader’s progress, not because of their incomprehensibility but because of their felicity. Describing Théo, for example, the narrator says, “Regulation envelops him, an ingested metronome.” Here, Théo wears regulation like a blanket wrapped tightly around him, but he also seemingly hears its demands for order and synchronicity coming from inside of him. The shifting metaphors make sense in a text where categories are slippery and boundaries permeable.

The three friends are all seeking an exit, in one way or another. The book’s title, Phototaxis, refers to an organism’s movement toward or away from a source of light. In Tapiero’s text, light—like so much else—is suspect. “If the apocalypse were a bringing-to-light,” Théo thinks, “we would let each other go blond under the sun, all curled up together.” The catastrophic conditions under which Théo, Narr, and Zev live might have revealed the full extent of society’s dysfunction and ugliness, but this knowledge isn’t necessarily beneficial. There’s such a thing, Phototaxis seems to say, as knowing too much, or staring too intently at reality.

Like the moths lured to Théo’s window by the luminous glow of his apartment only to be trapped between the panes, Tapiero’s characters are tempted by desires synonymous with destruction. Contemplating Théo’s eventual decision to die by suicide, Narr thinks, “Maybe Icarus wanted to fall, was drunk on this very desire. To leave everything behind, to submit the body to unpredictable forces.”

In the world of Phototaxis, where there are no good choices, pursuing oblivion is almost as appealing as it gets. Narr fantasizes about self-immolation, but she’s stopped by the thought of how people will impose a narrative on her death. The problem for her is that she already exists; any step she takes will already be the wrong one. Taking part in the rites of her society—education, career, marriage, parenthood—strikes her as a trap, while fighting the status quo is mere performance. She scorns “the solidarity gatherings that give citizens the impression that they’re taking part in something” and rejects the “orgasmic sense of urgency and war” that turns suffering into spectacle.

Allusive, polyvocal, dreamlike—Phototaxis is a haunting collection of responses to crisis: that of ecological decay and disturbance, political and social repression, wealth inequality, and existence itself. Near the end of the book, Narr has abandoned language, singing a wordless song about grief and disaster, forgetfulness and futility. If Phototaxis were a song, it would be the song of the death drive, using words, by turns poetic and obfuscatory, to chronicle how far we have fallen and how doubtful our return to grace.

Marisa Grizenko lives and works in Vancouver, on the unceded territory of the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations. She is the reviews editor for EVENT Magazine and writes Plain Pleasures, a monthly newsletter about books.