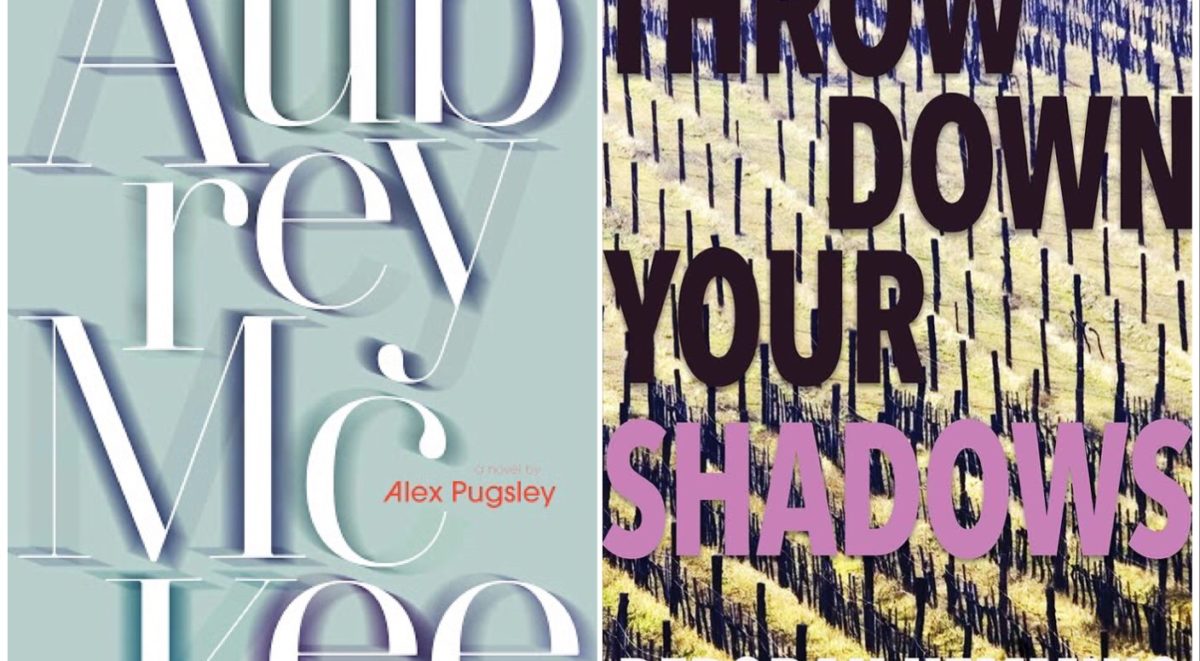

Throw Down Your Shadows

Deborah Hemming

Nimbus Publishing, 2020

Aubrey McKee

Alex Pusgley

Biblioasis, 2020

Review by Marcie McCauley

The marketing copy for Deborah Hemming’s Throw Down Your Shadows compares it to Emma Cline’s The Girls and Stephanie Danler’s Sweetbitter, whereas Alex Pugsley’s Aubrey McKee is described as reminiscent of J.D. Salinger’s Franny and Zoey and Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women.

Yet, comparing Hemming’s and Pugsley’s debut novels to each other demonstrates how widely perspectives vary even in shared environs.

Both authors focus on young characters who grow up in Nova Scotia. Hemming’s main character in Throw Down Your Shadows, Winnie, lives in Halifax only briefly as an infant, when she and her mother shared a friend’s basement in the Atlantic province’s capital city. Soon, however, Winnie’s home is the “white house with the blue door on the Gaspereau River Road” in rural Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley––the western part of the peninsula, along the Bay of Fundy.

Pugsley’s Aubrey McKee revolves around his main character’s hometown, which also happens to be Halifax. To him, it is “a city of bars—taverns, clubs, cabarets.” Aubrey’s a true Haligonian, but when readers meet him, he’s barely old enough to go to school, let alone bars. As he moves through his teen years, his perspective on Halifax broadens and shifts into disillusionment:

Either I wanted to be more than I was, or I wanted the city to be more than it was, and though I couldn’t hold in my imagination what I wanted these to be, exactly, I knew very drunkenly, very extremely, very finally, that I was choosing not to care about Halifax anymore, I didn’t see myself in Halifax anymore, I didn’t see a future in Halifax anymore.

Both Throw Down Your Shadows and Aubrey McKee emphasize the insulated nature of their characters’ early experiences. Their worlds are comfortable and contained until they are confronted with someone else’s contrasting experiences, leading them to discover how complex individuals are. These two characters’ external––and then internal––shifts are especially highlighted as they inhabit the same peninsula.

Winnie soon recognizes that each of the small communities in the Annapolis Valley are distinct. Even a short drive can lead to a substantially different place:

I noticed the creepy quiet. Virtually noiseless compared to Gaspereau. Not a single owl hooting; trees without secrets. I imagined the cul-de-sac was muffled by a large hand wearing a black, leather glove.

Aubrey observes his own different, in how the varied ethnicities in the city coexist in his “seaside city” where “the Scots-Irish and African-Acadian and Nordic-German gene pools mingle and stream,” where different “priorities are not always obvious.” One key observation of Aubrey’s Halifax is inherently true of Winnie’s Annapolis-Valley world, too: “Lives leak in and flow out of each other like a human version of the water cycle.”

Characters can inhabit a very small space, even in a city. Aubrey spells it out, noting the “wear-you-out thing about the place,” how “sexual, familial, and personal and professional lives all complicate with connection, alliance, and shared secrets, so much so that the citizens seem to be participating in some Grand Dysfunction.” Dysfunctions, grand and petite, make for good fiction; as Winnie and Aubrey mature, their shifting emotional landscapes occupy the foreground of their stories, overshadowing the geographical views.

Whereas Winnie is sixteen and reminisces about her younger years in Throw Down Your Shadows, Aubrey’s story unfolds from his early school days through graduation; for both, the fabric of their relationships with family members and friends stretches and pleats over time. In Winnie’s case, the focus is on her mother and three friends, all boys (friendships between girls and boys being largely absent in contemporary fiction, Hemming observes in her author’s note). The teens’ friendships are disrupted by the arrival of Caleb, whose family purchases a home and moves in to the area. Caleb is from away, and “seemed grown-up and committed to self-improvement” but “instead of blending in, he used his intelligence to stand out.”

Young Aubrey, too, values his friendships:

My God––to have a circle of friends within which my fledgling thoughts might find expression, discover their balance, and take wing was a tremendous deliverance for me. Cyrus and Karin, Gail and Brigid, Babba and Tom––they were highly cherishable items in my world. I gave my heart to them because they gave the possibilities of my life back to me.

These quotations reveal the contrast in Hemming’s and Pugsley’s syntax: one novel’s prose is unadorned and streamlined and the other’s is exuberant and highly emotive. With the security provided by her stylistic simplicity, Hemming can afford to experiment structurally, whereas Pugsley’s high-spirited narrative moves chronologically through time, with Aubrey casting a backwards glance at his coming-of-age and occasionally digressing to focus on more historical events.

Hemming’s temporal experiment, however, develops a predictable rhythm: she alternates between “after” and “before,” the chapters circling a fire at one of the Valley’s wineries. Not only does that Effect-Cause pattern create suspense, but it also reminds readers that we move through life via a series of hinged moments. In her author’s statement, Hemming explains that “we are forever ‘coming of age’ and so Winnie’s story looks at adulthood—and specifically, womanhood—not as a stage to achieve but as a space to continuously grow within.”

Aubrey acknowledges this continuous growth, too, and emphasizes its mysterious nature. “Adults, especially adult men, were impossibly remote and complicated entities. They seemed the result of a thousand decisions made in the generations before I was born,” he says. Aubrey’s observations of another boy reveal his own preoccupations and concerns: “Many who considered him a prodigy also thought him peculiar and there was a gaining minority who believed him trending toward outright psychopathy.” It feels like he has a thousand thoughts to every single thought of Winnie’s, creating a sense of an Aubrey-immersion rather than propulsion through the narrative.

Developing selfhood is the central theme in both novels. Winnie and Aubrey both struggle to negotiate rapidly shifting boundaries. Caleb’s arrival immediately and violently alters the dynamics of Winnie’s group; the opening scenes of working at the U-pick strawberry field and tubing on the river after work soon seem part of a simpler age. Readers experience Aubrey’s dislocation, too: when his parents divorce, he knows that he’s “supposed to pretend everything will be fine,” but this “improvised existence” feels awkward and distorted.

“I have never seen a place so obsessed with itself as Halifax,” Aubrey observes. Ironically, readers might wonder if they’ve ever seen a character so obsessed with himself as Aubrey McKee. His intense interiority and his love of words (so many words! Nearly 400 pages of words!) magnify this sense of self-obsession, whereas Winnie’s narrative is self-reflective but consciously controlled (for reasons attached to potential spoilers). If Aubrey had moved to the Annapolis Valley to take Caleb’s place, Winnie and the boys probably would have accepted him into their group. But rather than go tubing on the river, Aubrey would have waited in the truck with his childhood copy of Watership Down (replete with seventeen racist jokes told by a classmate recorded on the endpapers––a demonstration of how dramatically one’s awareness and experience of the world can broaden and evolve).

When any writer is compared to any other, any book to any other, and any character to any other, the conversation soon spills beyond its initial scope. As writer Emma Donoghue observed about a reader’s relationship with a book in a 2014 Guardian Book Club discussion: “It’s as if every reader reads a different book. The book doesn’t really happen until each of you cracks it open.” If every reader of every book could contribute marketing copy, there would be as many blurbs as readers. A single comparison is not an encapsulation but an invitation: it’s all about the conversation.

The marketing copy for Alex Pugsley’s debut novel could easily have commented on his declarative and ambitious prose being like Mordecai Richler’s or Pasha Malla’s, and the quirk and the vibrance of his characters more like Wayne Johnston’s or Zsuzsi Gartner’s. The marketing copy for Deborah Hemming’s Throw Down Your Shadows could have compared her sleek and definitive prose to Deborah Willis’ or Souvankham Thammavongsa’s, and the gentle but pointed exploration of integrity and responsibility more like Mona Awad’s.

Personally, the conversation between these books urged me to reflect on my own childhood and adolescence in Ontario––partly spent in a village and partly in a small city. The exercise of comparing and contrasting two novels is not far removed from comparing and contrasting versions of our own younger selves, with all the disappointments and wonders that comprise our personal growing-of-age stories. Hemming’s and Pugsley’s characters, living different lives in the same Atlantic Canadian peninsula, implore readers to have compassion for their own ever-evolving selves as well.

Marcie McCauley reads, writes and lives in Toronto (which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples––including the Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg and the Wendat––land still inhabited by their descendants). Her writing has been published in American, British, and Canadian magazines and journals, in print and online.