by Janice Weizman

In blogs, opinion pieces, and online forums responding to Alice Munro’s silence in the face of her daughter, Andrea Skinner’s revelations of sexual abuse at the hands of Munro’s second husband, I came across numerous responses that said things like: Alice Munro fans, apologists, enablers, and advocates…. YOU are all complicit. Your hero is actually a villain. And YOU all ignored it. That’s why you’re all in denial and are hypocrites.

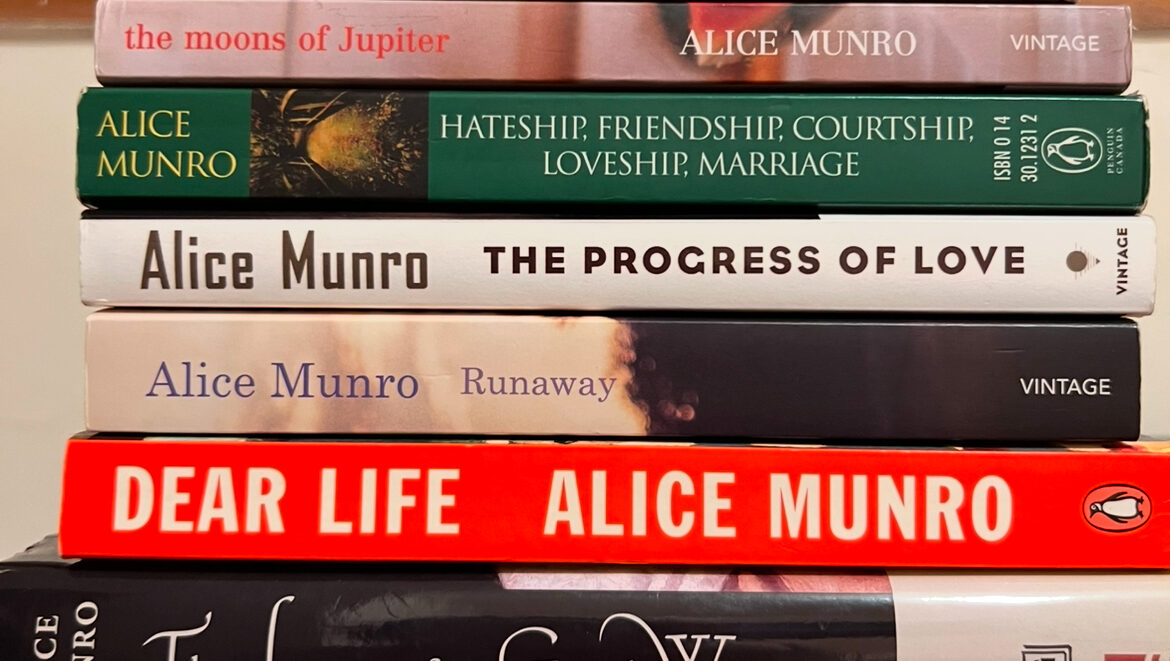

As a novelist writing my Ph.D. on Alice Munro’s work, the accusation is troubling. My research has little to do with Munro as a mother, or even as a person. But the shock, anger, and dismay around what has been revealed is so great, and the taint now on her name (and work) so powerful, that I’ve had to question whether there is an ethical dimension at stake in my choice to proceed.

I’ve been paying careful attention to both the story as it comes out and the reactions to it. One of the disturbing takeaways is how it has exposed the mechanics of the ways in which a community, even a literary community, can enable not only abusers, but also those who cover for abusers. It has illuminated how sexual abuse implicates entire families, communities, and societies. It has shown that given the choice between an uncomfortable truth and a comforting falsehood, people will often choose the falsehood.

We all recognize that writers, even gifted and cherished writers, are human, as flawed as the rest of us. And yet, because of their ability to put into words ideas, situations, and feelings that are not easily described, we expect them to see a little clearer, a little farther and deeper, and we expect that perspective to come with an ability to distinguish between right and wrong. Considered in this light, Munro’s betrayal of her daughter is particularly disappointing.

In her stories, Munro fearlessly turned her attention to the weakest and most maligned members of society. From the mentally challenged musicians in “Dance of the Happy Shades,” to the homicidal horror in “Child’s Play,” to the victimized Franny McGill in “Royal Beatings,” to the sick and disabled elderly women in “Mrs. Cross and Mrs. Kidd.” Munro’s work takes us directly into her characters’ lives and psyches in ways that recognize and respect their humanity. How could she perceive the dynamics at work in these fictional social constellations but ignore the very real experience of her own daughter?

My natural impulse in this situation was to turn to her writing, the sharp, surprising, and sometimes disturbing stories of girls and women negotiating the parameters of their lives. It doesn’t take long to notice a narrative pattern emerging − one in which her characters put themselves and their desires first, often at the expense of others. In “Passion,” the protagonist, who ditches her devoted fiancée after a life-changing escapade with his alcoholic half-brother, recalls how “it was as if a gate had clanged shut behind her” and that “the rights of those left behind were smoothly cancelled.” There is cruelty and blind narcissism in such a declaration, and Munro knows it.

Likewise, in “Family Furnishings,” a story whose backdrop mirrors Munro’s own life, a writer usurps a personal recollection shared by her father’s cousin, Alfrida, for her own literary purposes. “…the minute I heard it, something happened. It was as if a trap had snapped shut, to hold those words in my head.” When, years later, it becomes clear that her actions are the cause of a family rift, the narrator recalls “I was surprised, even impatient and a little angry to think of Alfrida’s objecting to something that seemed now to have so little to do with her.” In “The Children Stay,” a woman abandons her children for sexual adventure with her theatre director. Again and again, the theme of betrayal arises in her work, and though there is sympathy for the betrayed, the decision to betray is unequivocal.

As readers, critics, and the literary community rushed to revisit Munro’s stories in search of clues to where her work resonates with her life, mention has been made of Munro’s story “Vandals,” written around the time her daughter first confronted her with the story of the abuse. In the story, Bea’s response to Liza’s plea for help calls up Munro’s response to her daughter, and in retrospect we can only wonder about the flimsy justifications that Munro set up to ease her own conscience. Yet, for me, the more telling stories are those in which parents are painfully estranged from their grown children. There is Kent, in “Deep Holes,” who breaks off contact with his family for decades. There is the Juliet trilogy, in which Juliet callously avoids her mother when she most needs her only to realise, years later, that her own daughter, Penelope, has cut all ties with her. In “The Children Stay” Pauline’s children, whom she abandons in favour of her lover, “don’t hate her, but they don’t forgive her either.”

Even without knowing about Munro’s personal life, these stories of estrangement and severed relations give one pause. They depict situations of extreme familial dysfunction, which could only have come from some source of personal knowledge of the subject. Reading them now, they convey a strange, knowing remorse, a relentless awareness of an outrage that never goes away. It emerges from Munro’s work that she well understood the implications of her choices. Why, then, did she make them? The notion that there are aspects of a life that can never be known or understood is one that plays out repeatedly in her stories. The irony in the idea that she has, in a sense, become one of her enigmatic, unknowable characters has not been lost on her readers.

The dissertation that I am writing takes a philosophical approach to Munro’s writing, as it looks at her work through the lens of existential phenomenology. Heidegger (a controversial figure in his own right) posits that each of us is born into a world of social, economic, and familial circumstances from which we must build a life. Munro was born in a time and place that prized keeping secrets, hiding what was considered ugly, and showing the world a pleasing facade. The provincial Canadian society in which she was raised could be mercilessly judgmental and entirely invested in perpetuating convention, even when convention caused harm. Munro herself has said as much; her writing is a powerful and eloquent protest against these constraints, and a concerted attempt to show what happens when the individual brushes up against ingrained taboos. One would expect that such a writer would show a fierce brand of personal integrity in her own life, but apparently, Munro wasn’t brave enough or strong enough to make the obvious ethical choice.

I’m convinced that the revelations have made academic scrutiny of Munro’s work more complex and also more necessary. Like so many of her readers, I’m confused and saddened by what we have learned, and I’m still rethinking my own understanding of who she was. Many painful truths have come out of Andrea Skinner’s courageous revelation. Perhaps the most damning is that you can be a talented, sensitive artist and still betray your most deeply felt moral dictates, doing wrong even as you create brilliant art that testifies to your own failure.

_________________________________________________________________________

Janice Weizman is the author of the novels Our Little Histories, and the award-winning, recently reissued The Wayward Moon. Her essays, articles, and book reviews have appeared in many venues, including Queen’s Quarterly, World Literature Today, and The New York Journal of Books. She is currently at work on a Ph.D which reads the work of Alice Munro through a philosophical lens, and also a new novel set in Toronto.