Photo Credit: Owen Leong

Interview by Christopher Evans

Tom Cho’s current project is a novel with the working title The Meaning of Life and Other Fictions. His full-length debut was Look Who’s Morphing, a collection of fictions released by Arsenal Pulp Press for North America in 2014, and originally published in Australia by Giramondo. Look Who’s Morphing was shortlisted for multiple awards, including the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book, and is in its second Australian printing. Tom’s fiction has appeared widely in magazines and anthologies, most recently Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading. Originally from Australia and now based in Canada, his website is tomcho.com

PRISM is proud to have published “Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot”, a revised excerpt from The Meaning of Life and Other Fictions, in issue 54.3. Tom caught up with Prose Editor Christopher Evans, from his current base in Blairmore, Alberta, where he is the current writer-in-residence at the Gushul Residency Program.

“Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot” and The Meaning of Life and Other Fictions are steeped in theology and the question of God’s existence. I know you don’t have a background in theology, so how did you even begin to tackle such a topic? And, more to the point, why?

Scarily, I don’t have a background in so many of the academic disciplines that have fed into this project—philosophy of religion above all, as well as theology, art theory, cultural studies, and many others. (I do have a background in linguistics though—that was helpful for my discussion of prayer in “Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot”.)

One of the best decisions that I made for this project (The Meaning of Life and Other Fictions) was to engage an academic mentor—Dr Nick Trakakis, a philosopher of religion and himself a poet and editor. He advises on my philosophical scope and approach, explains concepts here and there, suggests texts to read, and gives feedback on my work.

Because I’ve had very little formal training in philosophy, I bring some very real limitations to my project. Sometimes the limitations are fruitful but they’re often frustrating too. Of course, there are limitations to doing philosophy within institutional contexts and it’s also important to do philosophy outside of those contexts. But at the same time, my feelings of inadequacy due to my lack of formal training have haunted my creative process.

As for why I’m writing this book: I think above all I want to write a book about religion that might model ways of approaching religion in our own lives—ways that are more open-ended and that require more tentative and less aggressive forms of belief.

You’ve said before that you were surprised that so few reviews of Look Who’s Morphing acknowledged the sexual explicitness of that book. Are you concerned with how The Meaning of Life and Other Fictions will be read? Are you worried that there will be more challenging aspects of the book that are glossed over in favour of surface reading?

I think virtually every author has some anxiety about how their work will be read. At the same time, I feel like I’m in a pretty good position to understand and appreciate that reading can be a really wilful practice. After all, my own fiction is full of wilful readings—for example, in Look Who’s Morphing, I do various mischievous and unauthorised things to films like The Sound of Music and Dirty Dancing. (This isn’t to say that I appreciate or agree with every wilful reading out there, of course!)

I don’t really know what a surface reading of The Meaning of Life and Other Fictions could even look like, but I do worry that there will be LGBTQ readers who will reject or even ignore the book, due to a belief that queer cultures are necessarily antithetical to religion. I’m definitely not denying—let alone excusing—the existence of homophobia, biphobia, transphobia and other oppressive thought in religion. But I don’t think that queerness needs to be set up as being antithetical to religion (for one thing, this usually relies on seeing LGBTQ people who have religious or spiritual affiliations as being politically conservative and ignorant, if not deluded.) I see LGBTQ readers as being among my core audiences and I hope that they’ll give the novel a chance, once it’s published.

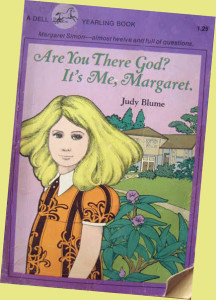

Pop culture has always featured heavily in your work—often in a heady, hallucinogenic way that seems to celebrate and satirize simultaneously—and “Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot” is no exception, referencing Judy Blume’s young adult novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret and the 1964 Audrey Hepburn film My Fair Lady. What drew you to those two particular pieces?

I think that artistic choices are inescapably personal so it’s no surprise that I usually have a strong, pre-existing personal connection to many of the pop cultural texts that I incorporate into my work. I grew up reading Judy Blume books and am a fan. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret exemplifies one of the best traits of Judy Blume’s books—that she credits young people with having complicated thoughts about complicated topics like religion. Her book stimulated some of my own complicated thoughts about religion—not only by my recent use of the book in “Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot”, but when I originally read this novel as a teen too.

I think that artistic choices are inescapably personal so it’s no surprise that I usually have a strong, pre-existing personal connection to many of the pop cultural texts that I incorporate into my work. I grew up reading Judy Blume books and am a fan. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret exemplifies one of the best traits of Judy Blume’s books—that she credits young people with having complicated thoughts about complicated topics like religion. Her book stimulated some of my own complicated thoughts about religion—not only by my recent use of the book in “Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot”, but when I originally read this novel as a teen too.

I also have a personal connection with My Fair Lady. My parents were divorced and, as a child, I spent every second weekend with my dad. He was a big fan of musicals and he owned a VHS player but very few VHS tapes. He mostly had VHS tapes of musicals, including My Fair Lady (he sometimes taught English to Chinese immigrants, and he especially loved all the My Fair Lady moments of language instruction). So my childhood was full of repeat viewings of scenes like this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVmU3iANbgk

Also, I work with a lot of devalued pop cultural texts. These texts have often been devalued because they’re associated with girls and/or women—as audiences and as protagonists. When I work with these kinds of texts, I not only “queer” my work, but I think that I “trans” it too, drawing on my own feminised history.

Another thing that features prominently in “Are You There, God? It Is I, Robot” is the role that technology plays in our lives. What’s your own relationship with technology? What do you see as its role in your daily life?

I rarely spend a day without my computer because that’s how I write and read, and I want to write and read every day. Basically, I’m a cyborg who’s writing a book that has a lot of robots in it.

You’ve been really successful with your short fiction—publishing something like seventy pieces over the last decade—so why write a novel? Was there external pressure to do so, or is it just a natural progression for you? How is the process different from writing short fiction?

I think there’s external pressure on many writers of short fiction to turn to writing novels, as if turning to novels were a natural progression (and obviously it isn’t). The short story is often conceived as being an immature form of writing that serves as the training ground for writing novels.

And yet I’m drawn to certain kinds of writing that are typically seen as immature. Maybe this was at least one reason why I originally envisioned my current project to be collection of (loosely-linked) fictions. However, I kept wanting more space to develop lines of investigation and to digress, so I eventually began calling the project a “novel”. That said, the full work is being built up in chapters, each chapter addressing a different philosophical enquiry, so arguably, by working in and accumulating these smaller units, I’m not abandoning the shorter form entirely. This leads to the inevitable fact that shortness is a relative quality anyway, so how meaningful is it to distinguish between shorter and longer forms of fiction? For this reason among others, the generic distinction between “the short story” and “the novel” doesn’t quite hold up for me. Ultimately, the distinction is influential because it’s institutional—it’s shored up by institutions like publishers and literary festivals.

Congratulations on becoming a permanent resident of Canada! What has your experience here been like so far? Have you noticed any major differences between working as a writer in Canada and working as one in Australia?

Thanks! Many of my Australian writing credentials aren’t recognisable to a Canadian audience and I have a lot of work to do in building my local credentials and profile (obviously a part of the experience of immigration for many immigrants). And yet, I’m not starting from scratch. By the time I became a permanent resident of Canada, Look Who’s Morphing had already been published by Arsenal Pulp Press (I was thrilled that the book was published by such a respected local independent publisher). I also already had a few publications in Canadian literary journals.

I’m still discerning the differences between working as a writer in Canada and in Australia, but here are two. My sense is that there are less writers’ festivals in Canada and that the writers’ festival circuit wields less influence here as a way of promoting literature. (This has its advantages, by the way—a festival model has limitations.) Also, as in the USA, authors in Canada often organise their own literary tours to promote a new book. Although these tours are typically organised in conjunction with their publishers, a fair amount of author labour and money (including lost income while touring) usually goes into this. This happens on a scale and with a frequency that I’m not used to seeing in Australia. (Again, this does have its advantages for writers in Canada and the USA—you learn a lot from organising and appearing on a book tour.)

Although I’m now a Canadian permanent resident, my plan has always been to continue contributing to both Canadian and Australian literature (and to hopefully build new audiences elsewhere too). I still have an Australian publisher and I’m not interested in choosing between Australia and Canada.

Christopher Evans is the Prose Editor of PRISM international. His short stories have recently appeared in The Impressment Gang, Nashwaak Review, Feathertale, and the UK anthology, The Speculative Bookshop.