Review by Mark Cutts

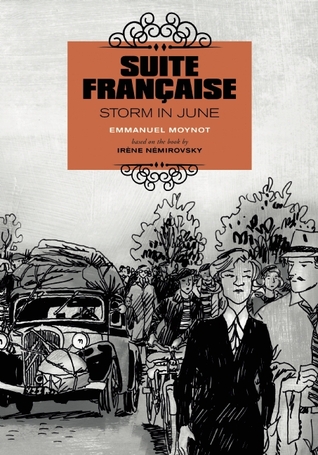

Suite Française: Storm in June

by Emmanuel Moynot

David Homel, translation

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015

Emmanuel Moynot’s graphic novel Suite Française: Storm in June follows four sets of people as they flee Paris and the invading German army in the spring of 1940.

We are introduced to the main protagonists as they prepare to leave their worlds behind and join the exodus to the countryside. The bourgeois Pericand’s are about to realize some harsh truths in the new disorder and there’s a touch of the Marie Antoinette as the well-meaning Pericand matriarch tries to find cake in a town without food. The Michaud’s, desperate to hear news of their son who is “fighting at the front,” hang precariously to their lowly bank positions. Corte and Langelet, writer and aesthete respectively, are incredulous at the interruption of their privileged lifestyle.

In the original novel, written by Irène Némirovsky at the time of the Nazi invasion and not discovered until the 1980’s, it was the upper classes that were held in most contempt. Moynot portrays this well. On the road to Tours, innocent honeymooners fall prey to Langelet’s selfishness when he tricks them and steals their petrol. As the situation grows ever more desperate, Corte bemoans the crumbling of social mores that leaves him mixing with “shopkeepers.” Towards the end of the novel we begin to see how the old order will resurface, as Paris lays untouched and ready for their return, with condition, but the likes of the Michaud’s are left to fend for themselves.

In the original novel, written by Irène Némirovsky at the time of the Nazi invasion and not discovered until the 1980’s, it was the upper classes that were held in most contempt. Moynot portrays this well. On the road to Tours, innocent honeymooners fall prey to Langelet’s selfishness when he tricks them and steals their petrol. As the situation grows ever more desperate, Corte bemoans the crumbling of social mores that leaves him mixing with “shopkeepers.” Towards the end of the novel we begin to see how the old order will resurface, as Paris lays untouched and ready for their return, with condition, but the likes of the Michaud’s are left to fend for themselves.

The large cast of characters, or perhaps Moynot’s desire to include all that Némirovsky wrote, sometimes asks too much of the images. In a similar vein, possibly because this is a translation from the French, the choice of words can sometimes seem overly direct. However, the subject matter is too weighty to be stopped in its tracks by a few clunky lines, and Moynot manages to keep all plates spinning and our interest piqued.

The scribbly line-art and the grey tones reflect well the chaos and uncertainty of that time. Because of this style, the large cast of characters tend occasionally to merge in the reader’s mind, but Moynot shuttles us back and forth between characters and families using titles for each section, and there is also a handy gallery of characters at the beginning of the novel.

Moynot’s choice of images is often striking. The haughty looking businessman and the wide-eyed bank workers are juxtaposed, for example, as the Michaud’s boss makes them walk to Tours while he drives his mistress. The Pericand’s struggles with their social conscience and Langelet’s love of beauty over humanity are all portrayed simply yet effectively.

Irène Némirovsky recorded the events that were unfolding around her before her arrest and subsequent death at an Auschwitz concentration camp. Moynot’s graphic novel makes a grave subject accessible, and while the nature of the original means this novel also remains unfinished, it is an amazing glimpse into a time when, for many, all was lost.

Mark Cutts writes about anxiety and related matters from his home in Canada, using fiction and non-fiction to share his ridiculous thought processes and thereby sow seeds of hope in all those who thought they were alone in feeling hopeless. Born and raised in the U.K., Mark spent a short time in Her Majesty’s Royal Navy, and a lot of time in abject poverty and despair. His journey has taken him from itinerancy to fatherhood, from self-medication to actual medication and beyond. And in between there’s been a lot of countries, a lot of fun, and a lot of navel-gazing. You can find him at http://www.mlacutts.com/