PRISM is proud to present an excerpt from our 2016 Creative Non-Fiction Contest winning piece, “Choosing Your Poison” by Krista Foss. The full piece is forthcoming in our Winter issue (55:2), arriving on magazine stands and in mailboxes shortly. This essay was written while Krista was the 2016-2017 County of Brant Public Library Writer in Residence, a position supported by the Canada Council for the Arts

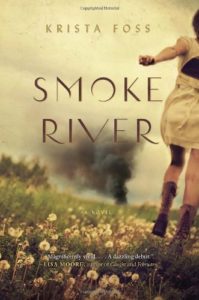

Krista’s debut novel Smoke River (McClelland & Stewart, 2014) was shortlisted for the North American Hammett Prize, for literary excellence in crime writing, and won the Hamilton Literary Award. Her short fiction has appeared in The Antigonish Review, Grain, EVENT, and Room, and twice was a finalist for The Journey Prize. Her essay writing, published in The Humber Literary Review and The Puritan, was nominated for a National Magazine Award and anthologized in Best Canadian Essays in 2016. She has an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia, and lives in Hamilton, Ontario, where she is a senior editor at Hamilton Review of Books and a cyclist. Check out Krista’s interview with PRISM Prose Editor Christopher Evans below the excerpt.

Choosing your Poison

By Krista Foss

We tried to poison Monique, which was unkind. Worse, if we had succeeded. Her sister Teresa offered her up. And suddenly we were three fates—Teresa, my sister, and I—spinning out the younger girl’s life like a length of yarn, measuring it, preparing to snip.

We were a trio of ten- and 11-year-olds plus Monique, a few years younger. Summer drooped and buzzed around us. Our houses backed onto a forest of large old trees whose shade cultivated every kind of weirdness—plants that were pendulous, hump-backed, striped, darkly green, hung with berries of obscene colors. I chose the bright red ones. I chose the poison.

Monique couldn’t stop giggling that day, tagging along with three older girls, sisters who usually rejected her. Her joy fizzed like carbonation. When she wasn’t looking, we rolled our eyes at each other.

One of us distracted her, another opened her sandwich and pressed the berries into it, hiding them like trafficked rubies. We ate our lunches and encouraged her to finish hers. Then we watched and waited.

It was an era when our parents’ parties all looked the same. Someone made an impromptu bar on a Formica counter: sweet vermouth like old blood, the unblinking eyeballs of cocktail onions and stuffed olives, bowls of sweaty ice. And at the doorway, a freshly scrubbed host saying, Choose your poison, folks, choose your poison, as tired parents moved toward the drinks, bewitched.

Years later, I understood the sad and sinister half-truth of those party invitations: we do choose our poisons. But just as often, they choose us.

Even as an adult, my sister was a roamer of forests, a daughter of Erebus, a maker of potions. The oil she infused with wild-crafted St. John’s Wort healed my swimmer’s ear; I still remember the relief when its slightly warmed trickle quieted my eardrum’s throb.

Does he look funny to you? she asked me one day, pointing to her son ,a toddler at the time.

He’s slightly yellowish, I said. What’s going on with his skin?

She was giving him a homemade tincture of yarrow to stop a chronic respiratory problem.

Where’s the yarrow? I asked. We were standing near her large backyard garden. She pointed to small bright buttons.

That’s tansy.

No, she said. It’s yarrow.

No, it’s tansy.

She moved toward the flowers and stared before bolting into her house and returning with a wildflower guide, looking up tansy, looking again at the plant in garden. Finally, she ran back to the kitchen and I heard the clink of a small tincture jar falling into the sink, emptied.

It was ages before we could laugh about that, and only when it was just she and I. Even then she misted up at the prospect of having nearly poisoned her child. Her son’s yellowish tinge faded within twenty-four hours. The side effects were hers to bear. She still believed in plants. Herself, less so.

CE: “Choosing Your Poison” begins with one of the best, quirkiest opening lines I’ve read in an essay, but the piece also centres on a deeply personal event. How do you balance raw honesty with compelling storytelling?

KF: I think of my life as a bunch of narratives that stack like nesting dolls. I can isolate any one story, tell it really well, and leave it at that. But that narrative is inevitably proximal to another, and part of a sequence of stories smaller and larger than it. So I like to focus on one story, but also connect it with a whole bunch of the others it touches, often out of sequence.

The process requires a split personality. There’s the risk taker who dominates the early writing and who is willing to meander, take big leaps, make wild associations. A lot of fun but nerve-wracking to hang out with. At some point that personality cedes to another, the editor who starts sniffing around for form and asking tough questions about theme and arc. She gets the final word. Often I’m really pissed at her.

One question that I’m sure is on everyone’s mind is: does Monique know that she was nearly poisoned? Do you seek permission from your family before writing about them?

I’d like to know the answer to that question as well. But I don’t. Monique’s family moved away within several months of that incident and we didn’t keep in touch.

Our families were very different. The era was different too: children had a lot of personal freedom and, where we lived, a large area to roam. We put things in our mouths. If you found an abandoned bottle or tin can, it was automatic to dare someone to drink what remained in it. A lot of stomachs got pumped in our neighbourhood. So when she didn’t get sick, we were pretty blasé about Monique.

Only later, when I hit adulthood did it occur to me how badly that berry sandwich could have gone.

When it comes to family, I write first and ask for permission later. I don’t ever want to write something to hurt someone—this is always a big concern—but asking for permission means the writing will never start or it will be self-censoring. My daughter and my partner read all my personal essays. They both have great instincts and are fair-minded. My daughter will call me out for being evasive or for over-reaching with an image or for treading on toes unnecessarily. She is unafraid to say she hates something which means sometimes I have to hang up the phone quickly before I get snarky. I trust her instincts. I did show this particular piece to my brother-in-law. He’s a writer too, and was very generous about it. He didn’t ask me to change a thing.

You’ve previously worked as a reporter, and I’m curious to know how you differentiate between journalism and memoir. How does it feel to turn the camera inwards? Is it possible to write about yourself impartially, or is that even a goal?

Reporting is a narrative-collecting machine. It’s fast and formulaic, and there’s always an “I” shaping the story—whether it’s declared or not—because to report something involves privileging a point of view (anecdotal leads, for example) or simply leaving out context and facts that confuse the narrative, or for which there aren’t the resources or will to collect. It’s the degree of partiality, not the absence of it entirely, that determines how complete, or fair, a story may be. And that changes minute to minute.

With memoir, the partiality is not only declared, but celebrated. The memoirist is just saying, let’s get naked about our bad tattoos, unfortunate late-night phone calls, and daddy issues, and see if there is a bigger truth in our struggle to do better. And if there isn’t a bigger truth, there’s probably at least an interesting way to arrange the material. It’s slower, and I think it’s harder, too.

With memoir, the partiality is not only declared, but celebrated. The memoirist is just saying, let’s get naked about our bad tattoos, unfortunate late-night phone calls, and daddy issues, and see if there is a bigger truth in our struggle to do better. And if there isn’t a bigger truth, there’s probably at least an interesting way to arrange the material. It’s slower, and I think it’s harder, too.

Because experience is mediated through the self, if you get the self out of the way—which I think is what it means to be impartial—there might not be anything left to say, unless you’re a Buddhist or a theologian. For now, I’m embracing the muck of idiosyncrasy. If ever I am fully impartial, I’ll probably stop writing, pick up a walking stick, and wander for the rest of my days.

In addition to your essays and journalism work, you’ve also published short stories and a novel, Smoke River. How do you define yourself as a writer? Are “journalist” and “novelist” separate compartments, or just points on a spectrum?

I was a bartender for as long as I was a journalist, and a teacher longer than any of them. I’ve also sold adding machine tape, and advertisements for orchestral programmes. Only once did I try to be a trapeze artist; it went poorly. I’ve been a mother, daughter, sister longer than anything. It’s all material. The writing—the wanting to do it, the not doing it, the doing it—has been the twine tying it all together, hauling it forward, giving it meaning.

Some of that material finds its best expression as fiction and some as non-fiction. So if I have to define myself, it would be as a struggling writer, because it’s always a struggle to determine how best to express yourself. I’m also a full-time writer which is terrifying, but I’m doing it anyway.

Christopher Evans is the Prose Editor of PRISM international. His fiction, non-fiction, and poetry have appeared in The New Quarterly, Riddle Fence, The Feathertale Review, Going Down Swinging, Joyland, Isthmus, and elsewhere.