Review by Amy Kenny

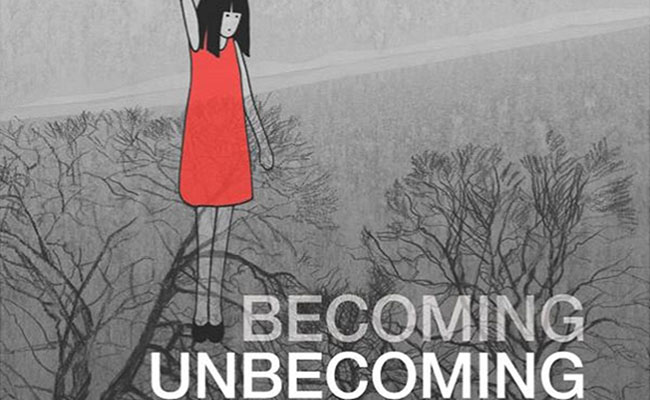

Becoming Unbecoming

By Una

Arsenal Pulp Press, 2016

This graphic novel is labelled memoir, but a better categorization might be subconscious.

That’s the word that comes to mind reading Becoming Unbecoming—an examination of violence, misogyny, and female sexual shame, told in graphic novel form.

The story plays out like a slideshow of hazy memories, which, for all their careful analysis, haven’t been fully processed. Or which have, but which the writer and artist (UK-based Una) hasn’t analyzed, to the same degree, in considering how to present them to an audience.

Becoming Unbecoming traces Una’s childhood growing up in Northern England during the 1970s. Her parents appear to lean on pills and alcohol in rough times. Her older sister is consumed with personal problems of her own. Family instability is part of the reason Una keeps it to herself when she’s sexually abused (in a mercifully restrained recounting—the event is hinted at only enough to let the reader know, in a general way, that abuse occurred).

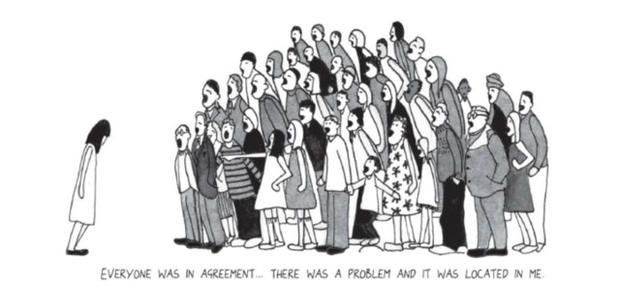

The other thing that muzzles her is the ever-present spectre of the Yorkshire Ripper, who’s in the middle of a decade-long murder spree that saw him kill, or try to kill, roughly 20 women. The social climate is one of fear and conflicting messages from media, school, police, and the community (see: women receive instruction on how to stay safe while boys are given no instruction at all, police search for evidence of loose morals among victims). As Una’s own sexual violence plays out against the murders, she comes to identify with the Ripper’s victims, internalize the “slut” label people put on them, and keep her mouth shut, even as her own assault becomes multiple assaults.

The other thing that muzzles her is the ever-present spectre of the Yorkshire Ripper, who’s in the middle of a decade-long murder spree that saw him kill, or try to kill, roughly 20 women. The social climate is one of fear and conflicting messages from media, school, police, and the community (see: women receive instruction on how to stay safe while boys are given no instruction at all, police search for evidence of loose morals among victims). As Una’s own sexual violence plays out against the murders, she comes to identify with the Ripper’s victims, internalize the “slut” label people put on them, and keep her mouth shut, even as her own assault becomes multiple assaults.

The book has an important message. Though set in the 70s, it illustrates many of the same patterns and attitudes around gender violence and victim blaming that are still prevalent in 2016. But the execution is a bit too clouded to relate the full power of that message.

Una’s drawing style initially seems pleasantly scrapbook-y, which works with the memoir genre. However, there’s no consistency in its cut-and-paste inconsistency, which becomes tiring.

Most images are rendered simply. The characters are drawn in thick, solid lines of black, white, and gray. They have unfussy, conical bodies, with soft, rounded hands, and dots for eyes and mouths. But they’re interspersed with more detailed sketches of light, delicate pencil. Occasionally, there’s a blend of the two styles—solid cartoon-y bodies with detailed, pencilled faces. Other times, pages consist of abstract watercolour landscapes. Still elsewhere, newspaper clippings are dropped in among drawings.

Throughout, text (in multiple fonts) appears variously in word bubbles, long vertical blocks, full pages of solid writing, or paragraphs scattered around the page in an order that’s difficult to follow. The combined effect is disorienting.

It’s possible this confusion is deliberate. In recounting her childhood, Una’s memories run into each other the same way you stitch together pieces of a dream the following morning. The narrative slides, sometimes without obvious segue, from Una’s musical tastes, to family life, to the Ripper murders, to dense sections of psychology, stats, and mini-essays on the justice system.

This mimics the way Una suggests information came at her as a kid—a wall of white noise, over which she has little control what filters through and mixes with other messages to become parts of the same whole. Nowhere is this better illustrated than the spare self-portrait that appears on a wide white page, where Una’s body is rendered in pieces. A red dress floating here. A thin white arm there. The black dots of her eyes and mouth lined up in a row beside her face, her hair.

Read this way, Becoming Unbecoming imitates Una’s real-time experience of growing up. However, there’s a reason the fragmented nature of that experience made a horrifying adolescence even more difficult to understand.

“Hindsight is a marvellous thing,” Una says on one page, talking about the effects of her abuse. The overall message makes the memoir worth reading, but its execution could have benefited from relating that message in a more structured way.

Amy Kenny is a Yukon-based writer and artist. Her fiction and poetry have appeared in Room, The Antigonish Review, and Time & Place. Her journalism has been published by Walrus, National Geographic, Canadian Geographic, Explore, and The Whitehorse Daily Star. She was named Journalist of the Year at the 2016 Ontario Newspaper Awards for her work with the Hamilton Spectator.