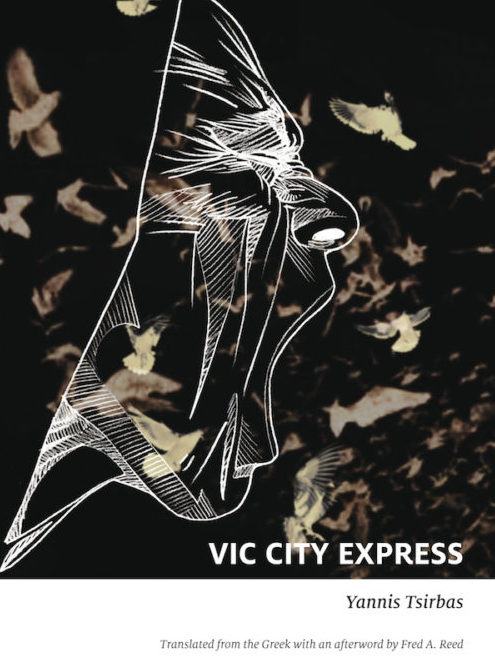

Vic City Express

Yanis Tsirbas. Translator: Fred A. Reed

Baraka books, 2018

Review by Sanad Tabbaa

Vic City Express by Yannis Tsirbas is, above all else, a practice in world-building. Similar to the little maps on the inside cover of pop fantasy books, Tsirbas builds Vic City for the reader street by street—giving a small neighbourhood a much greater weight than is commonly afforded to the concept of space in a novel. The vivid descriptions of urbanized poultry and childhood beatings accomplish the majority of the task of bringing the place to life, but a sizeable portion is achieved through the characterization. No character is ever referred to by name, and in order to empathize, the reader is forced to “live” within the neighbourhood, so to speak.

The novella has a basic premise that quickly, if uncomfortably, draws in the reader: a young liberal Europeanized Greek man is seated across from an aging working-class punk on a train to Athens. While on the train, the young man—the first-person narrator—is a captive audience to the stories and ideology of the radicalized, profoundly racist protagonist. The narrator is almost entirely passive, halfheartedly listening, and only ever commenting on the smallest of details—as if even internal criticism could be met with violence. The extent of his interaction with the reader comes from occasionally checking his phone, small forays into his spam mail showcasing another similarly dirty virtual reality. The protagonist’s monologue is occasionally interrupted by asides into the lives of other miserably poor denizens of Vic City, from stories of police brutality to starvation and everything in between.

Tsirbas’ greatest success with the work is in his unique and unwavering portrayal of the protagonist. There is no physical description of the protagonist whatsoever, to the extent of denying him a name. He exists only through the monologue he gives, imparting the idea that the reader is somehow spying on this private conversation along with the rest of the people on the train, as aurally enraptured as they are visually divorced from the image of the thuggish man. This serves as a testament to Tsirbas’ exceptional ability to place a reader within the space of his choosing. It is with this understanding of space that Tsirbas introduces the neighbourhood of Vic City.

Vic City refers to the area near the Victoria subway stop in Athens. It is a wholly uninspiring place, both by the author’s admission and my own (having seen it firsthand in the winter of 2018). Having no knowledge of the history of the area, my only memory of it is the distinctive smell of abject poverty: spices, sweat, cigarettes, and garbage accumulated from the trucks’ lack of desire to enter what basically amounts to a worse-smelling can of expired sardines. It is this context that allowed me to gain some insight into the plight of the protagonist—that of seeing his childhood neighbourhood devolve into what is essentially a immigrant ghetto. Permanent fixtures of his home have become impermanent and increasingly alien to him, and he feels entirely powerless to affect it in any way. Although the protagonist continually tells anecdotes that relate his past and present existence, it is almost entirely through his descriptions of the ever fluid neighbourhood of Vic City, and his reactions to this newfound change, that the reader is able to understand the inner workings of his personality and worldview.

Tsirbas uses the protagonist to paint a picture of a neighbourhood populated by immigrants, chickens, and transistor radios and streets inhabited by the stench of piss and fish (a disappointingly honest estimation). He connects his stories through placement in this urban geographical nightmare and in doing so raises this novella from a character study to something unique. Within this intricate geography, Tsirbas creates what I would consider to be a historical text, giving future and current generations a snapshot of a poverty-stricken, 21st century, post-economic-crisis Victoria through the eyes of the lowest common denominator of society.

That being said, although I enjoyed Vic City Express a great deal, I had difficulty tying together the events of the novella until my second read. The lack of chronology somewhat impacted my experience with the novel; on one hand, it was a window into another world, but I still felt separated by a pane of glass. This may also be a function of my not being Greek. The book is structured to best impress upon the reader the experience of hearing the rambling reminiscences of an angry, lonely stranger, and as such tends to jump backwards and forwards in time along the tangents that carry the protagonist’s stream of thought. Partially as a result of this, there is no overarching plot to speak of or satisfying conclusion; like a train ride it goes along and eventually just ends. Personally, this allowed me to be fully immersed in the voyeuristic experience of the train ride, but to another reader it could seem abrupt.

What I can respect is that writing it this way was obviously a conscious artistic choice, and not the only one of its kind in the novella. Tsirbas takes numerous risks within this short work and not all of them pay off. One striking example was a seven-page, free verse/train-of-thought monologue by the protagonist that contains a single comma, which is almost unreadable. That being said, the work as a whole is like a piece of performance art and uses just enough tether to the real world to deliver the most striking blow to the reader. Reading the book is not comfortable, but that seems to be the point.

On the whole, Vic City Express is a novella worthy of the praise that has been heaped upon it. It feels like bungee jumping into a dumpster: thrilling, disgusting, but above all memorable.

Sanad Tabbaa is an aspiring Jordanian writer currently based in Vancouver. He has done absolutely nothing of note in the writing world, but once got chased by a cow. Apparently, it was terrifying.”