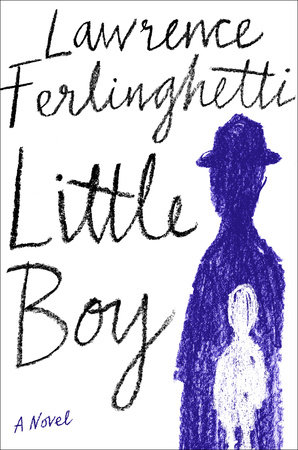

Little Boy

Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Doubleday, 2019

Review by B.H. Lake

In his latest book, Little Boy, Lawrence Ferlinghetti tells a story that took place in his teenage years. An older boy once held him down and refused to let him up until Lawrence admitted that he could not prove that he was alive. The young Lawrence could do nothing to prove his existence but continue to cry, “I am alive!”

This cry echoes from cover to cover. Ferlinghetti combines memoir with social and political commentary, while his use of language is stream-of-consciousness. He begins the book with memories of his childhood and teenage life. But when he moves into recounting the post-war years and his beginnings as a poet, the linear and chronological structure tumbles into a ferocious and poetic free fall. The horizontal narrative turns vertical and the reader cascades down through Ferlinghetti’s life, his past, and our present.

He regales the reader with stories of his family and of his friends, including Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. He speaks of Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, the summer camps of his youth, Ulysses, Google, Twitter, Facebook, the current United States government, and his recent visit to the apartment building in which he was born. As a centenarian, he offers the reader a unique perspective on each subject.

Ferlinghetti also speaks a great deal about climate change. He does not browbeat nor scream at the reader. He whispers. Through lush, heartbreaking, and delicate prose, he helps the reader to see a more personal side of the crisis:

“And it’s our Last Hurrah…oh daddy call me a cab the dusk is yawning and field mice squawk and run and hide from the rising tide the icecaps melting and me-me-me in my kayak trying to paddle over the horizon or maybe sailing into the wind and blow blow thy winter wind mankind is so unkind and manunkind populating the world while the kingdom of beasts may or may not be different with Rousseau painting The Dream a jungle scene with no computers and no monkeys on cell phones typing like mad and press the Save button to save us all on the last frontier or the last island like Gauguin on Tahiti having escaped civilization still trying to find the final island…” (p. 50).

He gives us pictures of the world we know and what is at stake: life, love, ball games, summer camping trips, leaves on trees that lean over the water, neighbourhoods, and laughing with friends. It may be that this is the most effective protest of all. The book’s final lines are searing and poignant enough to perhaps affect more change than any street demonstration.

Lawrence Monsanto Ferlinghetti was born on 24 March 1919 in Yonkers, New York. He founded the City Lights Booksellers and Publishers in San Francisco in 1953. City Lights has long been a meeting place for poets and other artists who were also political activists. Jack Kerouac, Neal Cassady, Allen Ginsberg, and Kenneth Rexroth are among those who came and went through its doors over the years. Following Donald Trump’s 2016 election win, Ferlinghetti created a new room in the bookstore named “Pedagogies of Resistance”, which is filled with materials devoted to historical revolutionary movements.

In 1955, he began publishing his Pocket Poets Series. The series included his own early poetry, such as Pictures of the Gone World, and major works of many Beat poets of the time, most notably Allen Ginsberg’s Howl in 1957. Ferlinghetti was arrested on obscenity charges for the publication of Howl but ultimately won. The case remains a landmark victory for freedom of speech in America. Now with his earnest cries to the reader in Little Boy, Ferlinghetti proves that he is as relevant in 2019 as he was in the 1950s.

A few days before Little Boy’s release last March, Lawrence Ferlinghetti turned one-hundred years old. He knows that its pages may contain his last literary battle cry. He calls us to look away from our technological gadgets and laugh with each other before it is too late. Even, perhaps especially, with people we do not know.

Over the course of the book, he sits in a quiet cafe and gives the reader scenes from within it. On two separate occasions, he attempts to strike up conversations with strangers. None of them reply. In the end, the silence returns to the cafe and he leaves.

Ferlinghetti urges the reader to revolution. Revolution against extinction due to the climate crisis, against closing ourselves off in favour of online “connection”, and against death in all of its myriad forms. He shows us what it means to be alive:

“What is all our writing about male or female if it is not based on that life force rooted in the heart of desire…Oh endless that splendid life of the world Endless its lovely living and breathing its lovely sentient beings seeing and hearing feeling and thinking laughing and dancing sighing and crying through endless afternoons endless nights drinking and doping talking and singing with endless lively conversations over endless cups of coffee in literary cafes on rainy mornings Endless street movies passing in cars and trams of desire on the endless tracks of light…” (p. 150-151). His earnest cries for us human beings to live are as much for us north of the border as it is for those in his San Francisco home.

In Little Boy, Ferlinghetti has decided not to die at all but rather to live forever within its pages. His continued cry of “I am alive!” reverberates through those who read him long after the book is closed.

B. H. Lake is a Halifax-based writer whose publications include The Furious Gazelle, Write Magazine and Atlantic Books Today. She spends her days working on her upcoming novel, In The Midst of Irrational Things.