Familiar Face

Michael DeForge

Drawn & Quarterly, 2020

Review by Kris Rothstein

A time of isolation. Bodies beyond our control. Unprecedented control by the state. As we live through a global pandemic, it is tempting to look to art for extra insight and meaning. Fiction has an uncanny ability to be speculative and, often, prescient. Familiar Face (Drawn & Quarterly, 2020), a wildly original new graphic novel by Michael DeForge, poses key questions about the dark side of human “progress.” The scenario retains enough similarities of life as we know it to be recognizable, while twisting and morphing crucial features to make readers feel immersed and uncomfortable.

DeForge’s book is an inventive combination of words and images. At the centre of the story is a society in which individuals and their environment are constantly being changed. These “upgrades” are actual physical alterations, performed by the state without explanation or notice. The nameless protagonist of the story evolves from a disembodied head with legs and two floating hands, to a rabbit that resembles a sock money, to an anthropomorphic exclamation point. A street might fold into itself while people drive on it; a hallway in an apartment might lead to a bathroom one day and a swimming pool the next.

The story is addressed to the main character’s former partner, Jessica, who has disappeared after a comprehensive upgrade to the apartment the two once shared. Finding no trace of her partner, the narrator journeys through surprise, fear, loneliness, and curiosity. The narrator applies for a roommate, positions which are filled by out-of-work actors. The roommate experiment is a disaster, but it leads the narrator to an awareness of growing social unrest. This––along with a rebellion on the streets, and the loss of her partner––opens her eyes to the dangers of passivity.

Familiar Face is a warning about the future as well as a commentary on the present, and it contains many echoes of George Orwell’s classic dystopian novel, 1984. It portrays an intriguing scenario which initially seems far-fetched, but starts to feel more and more plausible as the narrative develops. In this place, the government creates truth and reality, and has suppressed the liberty and free expression of its citizenry. The population is expected to accept lies and abandon ideas of truth. Both novels focus on surveillance and loss of personal control. They both imagine a political system which requires the pretense of choice and approval, and introduce an underground resistance (although in Familiar Face this movement is less likely to just be a government front, as it is in 1984). Familiar Face also takes inspiration from the writing of Franz Kafka, in the bizarre, complex, random bureaucracy which interferes with every part of daily life, determining how people will behave while leaving them puzzled and alienated.

Familiar Face includes important commentary on the insidious ways technology extends its control over our physical and psychological lives. Instead of Big Brother, the Familiar Face universe has personalized, intelligent computers that chat and interact just like a person, while also nudging, suggesting, and directing. This is suggestive of companies like Netflix and Facebook, which already direct personal tastes using algorithms and strategies to alter their users’ moods and decisions. We already cede choices to algorithms, and this story imagines what the next step might be. The constant changes orchestrated by the regime are meant to distract and disorient, even when they are touted as “optimization.” In this story, people don’t know what their surroundings––or even they themselves––will look like in the morning, but they accept that the technology knows what is best. While the inhabitants of this fictional universe retain some control over their emotions, DeForge makes it clear that they are allowing technology to make their choices, including decisions about how they should feel. The narrator often chats with her creepy personal computing helper, which provides a dizzying array of onscreen images and distractions. When she asks tough questions, the computer says something like “Oh, I bet you would like to listen to some soothing jazz or watch pornography,” and then sympathizes with her. It feels insidious and disturbing, probably because it hits close to the mark.

This fictional state does not approve of love, as close relationships are a potential danger to authoritarian control. This is perhaps one of the reasons they keep changing the physical aspect of people, so that they stop recognizing their loved ones. Eventually this lack of continuity will drive them apart––the main character knows that she will probably not be able to recognize or find her former partner. There is also a sense of secrecy in everyone’s jobs: workers are barred from discussing their tasks, even with family. The main character works in the complaints department, where complaints are read but never acted upon. Her sad and pointless job further disempowers her, reinforcing the mechanisms of social control. This description certainly rings true for many jobs today.

Despite the many physical changes to her body, the hero identifies throughout as a female, describing herself as a “girlfriend.” The meaning of gender in this world remains largely unexplored. This may be an oversight or we might interpret that the concept has become irrelevant (in which case gendered pronouns might have been jettisoned from the book). Either way, this issue is the only glaring example of a potentially fertile theme left unscrutinized.

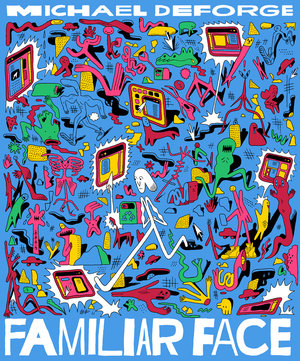

DeForge is known as an artist’s artist, respected and influential among other cartoonists. He is based in Toronto where he has published numerous books and web comics, and designed for the Cartoon Network series Adventure Time. His particular visual style would not typically attract my eye, but it is distinctive, creative, and perfectly appropriate for the subject matter. The physical book format, design, and drawing style are all small and intricate. The text is hand-written and undersized. The page layout runs from four square panels, to two rectangular panels, to a series of triangular pennants, with the occasional full-page illustration. The colour palette morphs as the story progresses, often combining colours which are not typically complimentary, like yellow and purple. The hues are bright and saturated, sometimes harsh. The style is weird, fluid, colourful, and squiggly, atypical for work labeled as futuristic or dystopic. Though DeForge’s style could be described as grotesque, the way he has deployed it in this instance is fitting for the subject material. It is sometimes unsettling, in the same way that all the changes are unsettling for the characters. Despite the visual intricacy, Familiar Face is easy to navigate, and its intricate story flows well.

One of the most intriguing themes of this story is its use of cartography as a metaphor. The practice of cartography becomes an act of emotional manipulation, political management, social engineering, and genetic alteration. Maps can be used for knowledge and opportunity or they can be used to limit freedoms. In the story, a nameless and faceless bureaucracy changes maps of streets and of bodies, and while the latter might not yet be a literal possibility, external institutions are already in a position to manipulate our emotions and what we believe to be true. Our public is forced to conform to external requirements, constrained in ways that are almost as extreme as physical modifications.

It is not a stretch to suggest that technology is actually creating reality, and DeForge makes that explicit. He also makes clear the ways technology can easily be exploited by totalitarianism and how it can be used to make people complacent and pliable. This is a plea for personal choice, and a call to stay actively engaged in community, relationships, and the world we live in.

Kris Rothstein is a literary agent, editor and cultural critic in Vancouver, BC. She writes regularly for Geist Magazine and can be found blogging about film, comedy, and books at geist.com/blogs/kris.