Hearts Amok

Kevin Spenst

Anvil Press, 2020

Review by Robert Colman

Kevin Spenst has been inextricably linked to Canada’s small press poetry world for the better part of the past decade. Prior to 2020’s Hearts Amok (Anvil Press) he’d published not only two other trade books but also a surfeit of chapbooks with the likes of serif of nottingham, Jackpine Press, and Alfred Gustav Press. The work in those publications consistently plays with form in the broadest sense of the term, incorporating everything from a sonnet sequence to visual poetry. Hearts Amok extends that reach while challenging Spenst to tackle perhaps the toughest topic of all––love.

Spenst has referred to Hearts Amok as the third in what he considers a poetic trilogy, and the new book does share similarities with his first, Jabbering with Bing Bong (Anvil Press, 2015), and second, Ignite (Anvil Press, 2016). Jabbering grabbed me instantly because it described, in part, my own experience of growing up a suburban kid in the 1970s and 1980s. Spenst’s suburb was Surrey, BC, in a landscape complicated by the presence/absence of a schizophrenic father and a Mennonite family legacy.

This is an unusual first book for its lyrical precision and sophisticated, mature voice. Take the following excerpt from “Jabberwock AD,” which contains a motive energy and logic of its own:

The future of Surrey is the Sally-Ann of

Horticulturalism. Charities of Engines

power Deep Fryers. The Nation-State

of the Unconscious is a Jonah’s Wait…

There are several imaginative leaps here––Surrey as “the Sally-Ann of Horticulturalism,” the “Charities of Engines,” the “Nation-State of the Unconscious” that, on second reading, make the reader ponder the meaning behind them. On first reading, though, its their sonic resonance that makes an impression––the assonance of “Surrey” and “Sally-Ann,” the rhyme of “Nation-State” and “Jonah’s Wait.” Many poems in Jabbering with Bing Bong offer straightforward narratives of pre-teen and teen life but the mix of those with poems that are more abstract create a balanced blend of both the real and surreal.

2016’s Ignite addresses Spenst’s father’s schizophrenia more directly, exploring the man’s lifelong struggle with mental illness. It is here that Spenst extends his range into visual poetry in work that was published as the chapbook Ward Notes (serif of nottingham, 2016). The visual allows the author to juxtapose an illness impossible to fully translate with what often amounts to terse, sparse poems of the lived experience.

Hearts Amok runs riot in language more consistently than in Ignite and with the intensity Spenst brought to the poem “Jabberwock AD” in his first book. This feels like the register in which he is most at home. The “plot” of Hearts Amok is a man’s search for love, and Spenst adopts a selection of “hobo slang” to capture the tramping nature of such a search, even if the search is often bound by the Surrey/Vancouver landscape. The tone, in the first section of the book, suggests a medieval traveller looking for love. “A Worshipful Deriding of Flimfam” the language employed towards this end:

Midway along our King George journey,

I nodded off in a claggy corner of the bus,

bum-rushed into a world wondrous strange:

a land of scrap metal mayhem for a throat-

clearing Escutcheon-Scraper, and a griffon

grappling a hornéd rabbit at Whalley’s corner.

This is a poet revelling in the possibility of language and a modernized version of the hard anglo-saxon consonants of a bygone time.

Through this memoir in verse Spenst sets out to capture every crush, every found and lost love in his life. Part of the challenge of the book is that some extracts feel like catalogue rather than the capture of something essential. For example, “Summer Crashes High School” reads, “After a stroke of dad news, my head plunked on the couch / like a pin-cushion. My tongue an old sock…” and then, “A year later, your / mouth enthralled my tongue of pins and needles…Our kisses called / it quits.”

The language dances, but struggles to reach beyond surface. Compare this to the play and purpose of “To Buss, Snog or Suaviate for a Decade in the Language of Yes” (and yes, many of the titles are poems entire):

Smack dab on Valentine’s Day after the Student

Council rose delivery event went awry, we ducked

the sharp questions of the rose-less by rabbiting

to a park where I sprung you a flower and we kissed

but you weren’t the one…

In this poem, Spenst captures a person searching and believing and ultimately failing to find “the one” in a variety of locales. The language of a catalogue and purpose meet energetically here. Elsewhere, poems could easily have been excluded from the collection without losing the breadth of experience Spenst wants to describe in his odyssey. This is especially true of poems that tell of what the protagonist did with a certain love interest, but little about how that person affected the journey of the narrator.

All in all, it’s Spenst’s energy that makes him special. His too-muchness––packed pages of alliteration and sonic crack––is a suitable register for youth and punch-drunkeness. And yet one of the most arresting moments for me is near the close of the book, as captured in this excerpt of the penultimate poem, “Epilogue Logos Flip And Sigh”:

We lay tracks together

from an alloy of old crowns

horizon-sliced light.

We rise and shine our raselbock

embossed handcar,

our three-wheeled velocipede

our mode of thought tracked

in tales of our long journey

into each other’s dilly-dallying.

Spenst plays with metaphor here to create an engaging, abstract image in “We lay tracks together / from an alloy of old crowns / horizon-sliced light.” This is combined with pacing that allows the reader to sink into the metaphor. The short lines and rounded sounds of “raselbock,” “embossed,” and “mode of thought” slow the pace, capturing the calm of finding a place, and yet: the hint of eternal play in the relationship comes through in “dilly-dallying.”

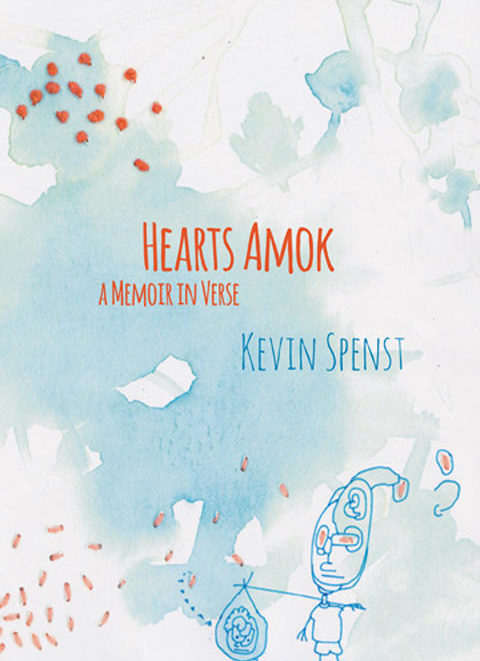

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the design of Spenst’s collections. As physical objects, each of his books serve as reflections of their character’s changing mindset. The cover of Jabbering with Bing Bong is a tightly drawn image of a many-eyed patchwork humanoid––odd, but suggestive of a single, multi-sided whole. Ignite’s cover suggests the cubist outline of a face but it is fractured and uncertain. Hearts Amok, by comparison, pares the visual down to strokes of watercolour combined with simple stick figure drawings. It’s almost as if, by the conclusion of this third volume, the weight of remembering has given way to the child-like simplicity the right place or person can, on occasion, instil.

Robert Colman is a Newmarket, Ont.-based writer and editor. His newest collection of poems, Democratically Applied Machine, was published by Palimpsest Press in Spring 2020. He received his MFA at UBC in 2016.