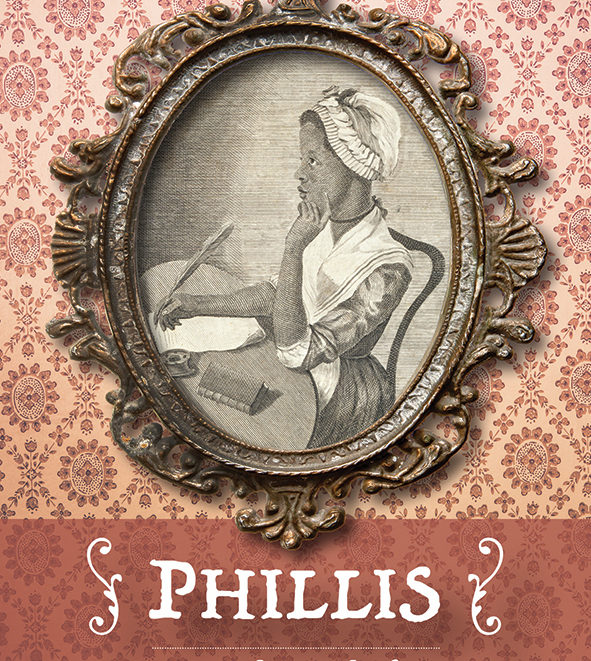

Phillis

Alison Clarke

University of Calgary Press, 2020

Review by Rachel Narvey

In Alison Clarke’s latest publication, Phillis (2020), Clarke cracks open time and form to craft a paean for the beloved eighteenth century poet, Phillis Wheatley.

As a child, Phillis was taken from West Africa and sold into slavery. The couple that purchased her named her after the ship that had taken her to America. As Christina Sharpe writes in In the Wake: On Blackness and Being: “How does one mark someone for a space—the ship—who is already marked by it?” Clarke reworks the intentional amnesia of white supremacy, placing Phillis at the centre of both a rich cultural past of West African heritage, and a burgeoning future wherein her work imparts hope to the Black lives that follow hers.

An original work in Phillis’ honour, the book features short sections of first-person narrative wherein Clarke takes up Phillis’ voice. Towards the end, Clarke shifts to poetry which increasingly becomes more free in its form. The book is divided into three sections that are titled in Latin––one of the languages that Phillis learnt (alongside Greek). The titles urge the reader to be attentive to the work they are about to explore, and centre the work as a point of refuge amidst a long journey.

As the book begins, Clarke’s words are neatly tethered to the page in prose, occasionally drifting into centre-set poems as Phillis reflects on her past and comes to writing, her “hopes and memories manifesting in black ink”. Only “Ancestral Memory” is evoked through Clarke’s use of colourful imagery, “a tapestry of … a dark cerulean, Swirls of fuchsia and orange … Merging into a crescendo / of emerald, gold, and vermillion”. Phillis’ ancestors are also vocalized on these pages, gifting Phillis both intention and inspiration. In this way, Clarke breathes into Phillis’s lineage, imbuing her talent as a writer with destiny and even divinity: “Ancient Ones … their words are music, an encouragement, a wave of love flowing into me … my veins are vessels to their spiritual core”.

Throughout Phillis, Clarke navigates the dislocation Phillis faces as a racialized child forced into slavery, imbuing this rending with the power of transformation:

From the ashes, the ashes, we often have to transform … start again a foundation, making it anew: from the sorrowful sounds, that music on the ship, they say it’ll morph into a new music form … that will belie what we have been through, a bird of song, but one that wails … we have done this so many times in memoriam …

In Clarke’s hands, Phillis’ life and work becomes a conjuring, a dowelling rod leading toward the brilliance of the Black diaspora in the face of systemic racism. As Clarke plunges forward into the time after Phillis’ life, each poem’s form becomes more shifting and malleable. Phillis’s name dances around the page, becoming “a call”, “a / meditation” “a stance, / in grace” for figures like Barbara Lee and Marcus Garvey.

Clarke adeptly loses time’s apparent linearity, using her words to weave Phillis out of the injustice of young death, of a future where “you just don’t know, you just don’t know what kind of impact you will have The reader, the observer, the one who dives into your words, you just don’t know”. By weaving Phillis’s voice with the future lives she would come to influence in this text, Clarke brings the poet forward into peace, positing a cosmology where Phillis can “hear, see, those who [she has] shaped, their lives like river beds birthed by stone, sand, and sediment”.

Though Clarke is not directly a part of Phillis’ lineage, she highlights their shared experiences as women of colour connecting them as writers. In the book’s afterword, Clarke describes how she came “to know Phillis” during an English literature course she elected to take while getting her sociology degree at the University of Alberta. For Clarke, Phillis became a figure of inspiration and encouragement: “her spirit is insisting I do not give up—in any way shape or form.” It’s without a doubt that readers of Clarke’s book will come to be dazzled by Phillis too, the spirit, courage, and talent of a writer who envisioned a just world that is still unfolding.

Rachel Narvey is a student journalist and teacher currently based on Treaty 6 territory, amiskwaciwâskahikan/Edmonton. This coming June, she will graduate with an MA in English Literature from the University of Alberta.