Brighten the Corner Where You Are

Carol Bruneau

Nimbus Publishing, 2020

One Madder Woman

Dede Crane

Freehand Books, 2020

Review by Marcie McCauley

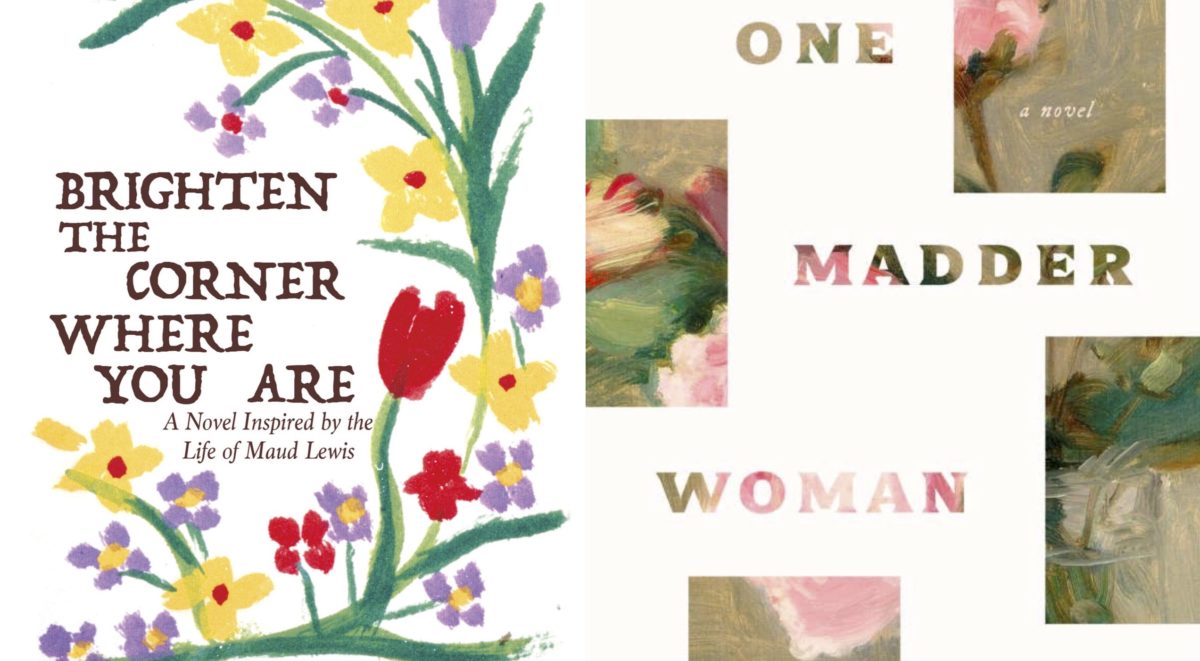

The cover of Dede Crane’s 2020 novel reveals the French Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot’s painting Peonies partially, as though a stencil is laid across the image. Even the title’s letters contain only bits of pink petals and green foliage that spell One Madder Woman—an appropriate reminder that Crane’s work involves revelation and display, but also selection and sleight-of-hand.

Carol Bruneau’s 2020 novel Brighten the Corner Where You Are also fictionalizes the life of a female artist: east-coast, Canadian painter Maud Lewis. The cover features artwork from one of Lewis’ notecards—also flowers, in yellow and purple and red, four-petalled blooms and tulips with bold green stalks.

The facts of these artists’ lives suggest these novels would contain polarized experiences. Morisot’s nineteenth-century life in Paris, France, showcases wealth and privilege; she has relationships with other artists and is connected to a burgeoning avant-garde community, with proximity to adjudicators. Lewis’ twentieth-century life in Digby County, Nova Scotia, reflects limited economic opportunity and physical hardships; she works alone, without the knowledge or support of other artists, largely in isolation.

As imagined by Dede Crane and Carol Bruneau, however, the lives of Berthe Morisot and Maud Lewis contain marked similarities in motivations, challenges, and influences. Even when it comes to their use of colour—so visibly different in the novels’ covers—there is a surprising connection between Morisot and Lewis.

One Madder Woman, by Dede Crane, is the Pacific-coast author’s fifth work of fiction. The bulk of Crane’s Morisot novel focuses on the years preceding Morisot’s marriage and motherhood—including her response to Édouard Manet’s revolutionary Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, part of Le Salon des Refusés in 1863, which Morisot recognizes as sacrilege based on its “[r]aising the mundane to the level of art.”

Berthe first discusses painting with her sister, Edma, and the two observe Édouard’s fascination with black: “He’s been trying to find the bottom of it and can’t.” Berthe is familiar with Goethe’s Theory of Colours and Aristotle’s idea that “the aim of the artist is to represent not the outward appearance of things but their inward significance.” Crane’s imagined Morisot experiences her world through colour and light: “As light through Monsieur’s studio windows brightened or faded, the flowers, fruit or plaster cast became less a solid object than a stream rushing under clouds and sun.”

Both Berthe and her sister, Edma, however, feel separate from serious artists. Evidenced by Mme Mamet’s remark to Mme Morisot: “Édouard has told me what talented painters your daughters are. A shame they’re not men.” The sisters’ wealth and privilege affords them leeway but, in the girls’ presence, the artist Rosa Bonheur is mocked: “Rumour was she kept a pet sheep in her third-floor appartement where she lived with another woman who was not her sister.”

When Manet later establishes an alternate alliance and venue for revolutionary artists in 1867 and invites Berthe to participate, Mme Morisot questions its respectability: “What kind of men’s club seeks to include a woman in their business?”

Berthe is consistently dedicated to her art (and, increasingly, to Édouard Manet), and she resists the formal, familial attachment that Edma chooses. Berthe strives for independence: “Despite my best interest, I would gather like kindling the pent-up jealousy of my mother, the hurt and shame of my sisters, the blithe bullying that surrounded us, to fuel a rage that cleared my vision in ways I’d yet to understand.”

Crane deftly situates readers in time and place, describing Paris as a “destruction-in-progress”, “fluid and unreliable”, and “more a question than a city.” Descriptions emerge vis Berthe’s privilege, but subtly expand, hinting at another perspective:

Up the winding hills of Montmartre, shadowed people in doorways and alleys stumbled, argued, embraced. A squalling mob of children ran across the narrow street in front of us and our driver yelled and snapped his whip at them. Through an open window came the gulping cries of an infant. I imagined it had been crying since birth, abandoned in a dresser drawer or apple crate. The smell of slop. Of cooking meat and sour perfume rode the air alongside other scents I had no names for.

Crane’s astute observations are often wedded with imagined emotional experiences: “A chickadee hopped along the terrace in search of crumbs. The humiliating silence persisted.” Chickadees are linked with humiliation in Maud Lewis’ life, too, when Carol Bruneau’s Maud describes two young girls who “reminded me of chickadees, dressed alike in dark brown, yellow, and cream-coloured outfits,” who stop by with their brother and parents. Maud’s husband Ev “got a kick out of little children, especially the girls,” and is left alone with the children while their parents admire Maud’s artwork. Later, they lodge a complaint against Ev.

Brighten the Corner Where You Are, by Atlantic-coast author Carol Bruneau, is the author’s tenth work of fiction, the bulk of which is set in the Nova Scotia landscape that also inspired Maud Lewis’ artwork: farms, villages, and coastlines.

Maud is not motivated by concepts; she is inspired by her surroundings. She paints “Arcadia’s houses and stores backing onto the river where fishing boats with bright red, green, and blue hulls bobbed on the incoming tide.” She earns a few dollars by repeating patterns that neighbours admire, selling first notecards and later paintings. However, even with word-of-mouth success, she charges very little and struggles to meet demands.

Maud’s obstacles are personal and social. As a girl, she “heard words like arthritis and rheumatism and others that made Mama shake her head in wonderment,” and she escaped into art to evade classmates’ teasing. After her mother dies, Maud realizes that not everyone recognizes her talent, including her Aunt Ida, who thinks Maud is “a little old to be spending every waking moment on a hobby.”

Grown and married, her husband Ev adopts some domestic duties, cuts boards for her to paint on and, later, even outlines her most popular patterns, which eases the physical strain based on Maud’s physical ailments. Some people think she isn’t “up to the task of making art, real art, that what [she] did was grown-up child’s play” and even some of the people who buy her painted sea shells say “they could paint just as good themselves.”

Yarmouth County is described as a “patchwork of woods and fields,” which Bruneau’s imagined Maud says is “a piece of paradise some called the arse-end of nowhere.” And although there are no shadows in her artwork, Maud’s observations sometimes tend towards darkness: “A whiff of turpentine or sardines mixed with the smell of tobacco smoke: that would be the extent of the earthly spirit I would leave behind to console and comfort him.”

Bruneau’s author’s note states: “…I suspect the reality of [Maud’s] experience lies in between abject darkness and cheery sunshine, in the grey areas of shifting light. Not to sugar-coat any aspect of Maud’s life, but in dramatizing parts of this shadowy ground, I ask you to remember that, as Margaret Atwood says, all fiction is speculative.” Both Crane and Bruneau acknowledge the importance of their research and share specific references for readers who are intrigued by the intersection between historical fact and creative imagination—who appreciate and ponder how novelists assemble alternative realities.

Nonetheless, with Maud’s artwork, the “blue, brick-red, and green [pastels], were worn to nubs while the beige and grey looked brand new”. Because “it’s colours that keep the world turning, that keep a person going”. Even in painting a crow—recall Manet looking for the bottom of black—Maud uses blues, greens, oranges, purples, even red: the “sun caught the rainbow there.”

Berthe Morisot attaches a particular importance to red, which “enthused the painting with the irresistible.” Early on, she slashes red across a model’s hair like a “secret signature”—“my hidden dare and quiet revolution.”

In the week that I read One Madder Woman and Brighten the Corner Where You Are, I also discovered a fictional artist in Alecia McKenzie’s A Million Aunties (2020). He has travelled to a friend’s aunty’s home in Jamaica, to recover from a loss, and he recalls this advice from an art teacher: “Painting flowers is political action,” she said. “When people bully you, you paint flowers. When they burst into your house and shoot at your family, you paint flowers. When they tell you that you shouldn’t be an artist but a basketball player, you paint flowers.”

In this sense, Berthe Morisot’s trademark scarlet and Maud Lewis’ unapologetically vibrant petals and feathers are political action. Their revolutionary acts remind readers that self-expression is both bold and intuitive. As different as the blooms on these book covers are, their indomitable spirit bridges centuries and continents.

Marcie McCauley reads, writes, and lives in Toronto (which was built on the homelands of Indigenous peoples––including the Haudenosaunee, Anishnaabeg and the Wendat––land still inhabited by their descendants). Her writing has been published in American, British, and Canadian magazines and journals, in print and online.