Interview by Emily Chou

Translation to English of Alex Simões’ responses by Carolyne Wright

PRISM’s Emily Chou sits down to speak with Alex Simões and Carolyne Wright about Alex’s poem “Cemetery of the New Blacks,” translated by Carolyne and published in our WONDER issue (60.1). Blunt and unflinching, this poem explores the urgency and relevancy of past atrocities. Read on to learn more about where Alex (whose answers have been published in English and in Portuguese) finds inspiration and influence, Carolyne’s thoughts on the role of translation, and their collaborative process. You can order a copy of our WONDER issue here.

Emily Chou: Alex, please tell us a little bit about yourself! Where did your poetry journey begin and where has it taken you? What has inspired your work lately? You mentioned that you’ve been writing a book through the pandemic, which I’m sure poses its unique challenges. Has this strange new world we find ourselves in changed the way you approach your work?

Alex Simões: I am a poet and performer born and raised in Salvador, Bahia. From one month after my birth until I was 21, I lived at the address, 1 Avenida Bahia, and I regard this as a happy coincidence. I was raised by my paternal grandmother, and I was the first grandchild in a house where I was the only child until I was five years old. Although I socialized with children on my street and at school (I began attending preschool when I was a year and a half), I had a very solitary childhood at home. The books on the shelf always fascinated me, and I remember that I learned to read at age five, very much motivated by comic books, naturally with the support of preschool classes and with a very early exposure to literacy—at least compared to the neighbour kids. I remember that I read my first children’s novel at the age of seven, and I was a compulsive reader of encyclopedias. I wanted to be an astronomer (not an astronaut, because I was afraid of heights), and I remember that, having read in an encyclopedia that the planet Venus was unfathomable, I used to design probes for Venus, and my project was to create a probe to research this planet. I was a good student, but my grades in math were always average. My fourth grade teacher told me quite seriously that with my performance in math, I couldn’t be a good astronomer. I must have been ten years old when I decided that I would be a poet.

A lot has happened since then. The answer as to what I wanted to be changed many times, but I always wrote poems, or tried to write poems. In my teens I did theater and dance and played sports. And in high school I had an excellent teacher, Célia Adler, who taught us to identify the characteristics of modernist poems. She used to give us exercises and exams in which she included excerpts from poems for us to identify. The poets were Manuel Bandeira, Cecília Meirelles, Carlos Druummond de Andrade, and João Cabral de Melo Neto (among the greatest modernist poets of Brazil). I did well in literature classes and helped my classmates with their studies. At some point I realized that it was easier to read the complete works of these poets than to memorize their main traits. Reading the complete works of these authors when I was fifteen or sixteen years old meant a lot. That’s why I dedicated my first book Quarenta e Uns sonetos catados (Forty-one Collected Sonnets, 2013) to my teacher Célia Adler and to Professor Rosa Virgínia Matos e Silva, who was my professor in my university course in Letters, where she taught History of the Portuguese Language and was a mentor in a Research Project for which I had a scholarship; but my major subject was Theory of Literature.

This longish story is by way of saying that I have had many influences, which have varied over time, but the Brazilian modernist poets have been a constant, and this has a lot to do with my experience in school.

During the Covid lockdown, which I strictly followed for a year and a half—and follow even now with some flexibility—I have spent most of my time at home; I published one book in April 2021, after having published a co-authored artist’s book, with visual and discursive poems, in December 2020. I’m currently working on a book, a collection of poems, published and unpublished, that have Bahia as a locus and/or theme. I have worked with poems in different forms, because I consider myself a formal poet. For a long time I worked mainly in fixed forms, but at some point I began to go beyond ostinato rigore and search for a way to bring to poetry the issues that affect me as an individual who is Black, gay, living in a racist and LGBT-phobic society, and always establishing dialogue with other poets, especially the canonical ones of Brazilian modernism.

In recent years, I have been interested in a discursive and visual approach to poetry, and in performance, as strategies like cartography and ethnography. The artist’s book, no meu corpo o canto: #experimentoscomletrasurbanas (in my body the song: #experimentswithurbanletters), in co-authorship with the collective Tanto, is comprised of visual poems in which I make photo-montages of signs that I photograph with my cell phone in a given region. This book deals with visual and discursive poems produced exclusively in Salvador, but I have been doing these experiments elsewhere, including in Chicago, when I participated in an artist’s residency exchange in 2018. The book I published in 2020, assim na terra como no selfie (on earth as it is in the selfie), is a collection that features many different phases of my poetry, which have in common the discursive polyphony based on different procedures, ranging from traditional fixed forms, such as the sonnet, to graphic-visual and melodic experiments. The book minha terra tem ladeiras (my land has slopes) is a collection of poems, published and unpublished, set in Bahia. It was a very interesting exercise to realize that many of my poems deal with Salvador, a city in which I move around, but which is also very informed by a tradition that goes back to the baroque poet Gregório de Matos, who was a performer avant la lettre.

Although these last two books of the pandemic are collections, they both have unpublished poems written during this period. One question that has been occupying me in my creative process has to do with non-creative writing—with the processes of appropriation, using ready-mades, since before the pandemic; but more specifically now I’ve been thinking about how to reuse materials—those from writing, those from visual poetry, and those from life. Mottainai is a Japanese word that deals with this unpleasant sensation in the face of waste, and I have been thinking about how this feeling, that in its origins my language-culture does not name, has been a motto of my creative process. I even suspect that this may be the name of the next book, which should only be ready in two years.

SOU UM poeta e performer nascido e criado em Salvador, Bahia. Vivi desde 1 mês de nascido até os meus 21 anos no endereço Avenida Bahia, número 1 e trato essa circunstância como uma feliz coincidência. Fui criado pela minha avó paterna e fui o primeiro neto, numa casa em que eu era a única criança até os meus 5 anos. Embora socializasse com as crianças na minha rua e na escola (desde 1 ano e meio eu frequentava na pré-escola), tive uma infância muito solitária dentro de casa. Os livros da estante sempre exerceram um fascínio e lembro que me alfabetizei aos 5 anos muito motivado pelas revistas em quadrinho, naturalmente com o suporte das aulas dfa pré-escola e com uma exposição muito prematura ao letramento, ao menos em comparação com meus vizinhos. Eu lembro que li o primeiro romance infanto-juvenil aos 7 anos e era leitor compulsivo de enciclopédias. Queria ser astrônomo (não astronauta, porque tinha medo de altura) e lembro que por ter lido em alguma enciclopédia que o planeta Vênus era insondável eu desenhava sondas para Vênus e meu projeto era criar uma sonda para pesquisar este planeta. Era bom aluno, mas minhas notas em matemática estavam sempre na média. Minha professora da 4a séria me disse que com meu desempenho em matemática, eu não poderia ser um bom astrônomo. Devia ter 10 anos e decidi que seria poeta.

Muitas coisas aconteceram desde então. Mudei muitas vezes a resposta sobre o que queria ser, mas sempre escrevi poemas, ou tentativas de poemas. Na minha adolescência fiz teatro e dança e pratiquei esportes. E no ensino médio tive uma excelente professora, Célia Adler, que nos ensinava a identificar características e poemas de modernistas. Ela fazia exercícios e exames em que colocava trecho de poemas que deveríamos identificar. Os poetas eram Manuel Bandeira, Cecília Meirelles, Carlos Druummond de Andrade e João Cabral de Melo Neto. Eu era bom nas aulas de literatura e ajudava as minhas colegas a estudar. Em algum momento entendi que era mais fácil ler as obras completas desses poetas do que decorar as suas características. Ler as obras completas desses autores quando eu tinha 15 ou 16 anos foi muito significativo. Por isso eu dediquei meu primeiro livro “Quarenta e Uns sonetos catados” (2013) à professora Célia Adler e à professora Rosa Virgínia Matos e Silva (esta foi minha professora na graduação em Letras).

Esta longa história é para contar que tenho muitas influências, que variam no tempo, mas os poetas modernistas brasileiros são uma constante e isso tem muito a ver com a experiência da escola.

Durante a quarentena, que segui rigorosamente por 1 ano e meio e mesmo agora com alguma flexibilidade, passo a maior parte do tempo em casa, eu publiquei 1 livro em abril de 2021, após ter publicado um livro de artista com poemas visuais e discursivos, em coautoria, em dezembro de 2020. Atualmente estou trabalhando num livro que é uma antologia de poemas, publicados e inéditos, que têm a Bahia como locus e/ou tema. Tenho trabalhado com poemas de diversas formas, porque me considero um poeta formalista. Durante muito tempo trabalhei principalmente em formas fixas e em algum momento comecei a perseguir para além do ostinato rigore um modo de trazer para a poesia as questões que me afetam como subjetividade que é negra, homossexual, vivendo em uma sociedade racista e lgbtfóbica e sempre estabelecendo um diálogo com outros e outras poetas, especialmente canônicos do modernismo brasileiro.

Nos últimos anos, tenho me interessado numa abordagem da poesia, discursiva e visual, e na performance, como estratégias como cartografia e etnografia. O livro de artista “no meu corpo o canto: #experimentoscomletrasurbanas ”, em coautoria com o coletivo Tanto, é composto de poemas visuais em que faço fotomontagens de letreiros que fotografo com meu celular em uma dada região. O livro trata exclusivamente de poemas visuais e discursivos produzidos em Salvador, mas tenho feito esses experimentos em outros lugares, inclusive em Chicago, quando participei de um intercâmbio-residência artística, em 2018. O livro que publiquei em 2020, “assim na terra como no selfie”, é uma antologia que apresenta muitas fases distintas da minha poesia, que têm em comum a polifonia discursiva pautada em procedimentos diversos, que vão das formas fixas tradicionais, como o soneto, a experiências gráfico-visuais e também melódicas. O livro “minha terra tem ladeiras” é uma antologia com poemas, publicados e inéditos, que se passam na Bahia. Foi um exercício muito interessante perceber que muitos poemas meus tratam de Salvador e de uma cidade que é a que eu circulo, mas que é também muto informada por uma tradição que remonta ao poeta barroco Gregório de Matos, que era um performer avant la lettre.

Embora esses dois últimos livros da pandemia sejam antologias, ambos têm poemas inéditos escritos durante esse período, Uma questão que me vem ocupando meu processo criativo tem a ver com a escrita não criativa, com os processos de apropriação, ready-mades, desde antes da pandemia, mas mais especificamente agora tenho pensado sobre como reaproveitar materiais, os da escrita, os da poesia visual, e os da vida. Mottainai é uma palavra japonesa que trata dessa sensação desgradável diante do desperdício e tenho pensado em como essa sensação que a princípio minha língua-cultura não nomeia tem sido um mote do meu processo criativo. Desconfio inclusive que será este o nome do próximo livro, que só deve ficar pronto daqui a dois anos.

EC: The punctuation in “Cemetery of the New Blacks” is so particular and specific. How did you decide this was the way you wanted the poem to look and feel? Did it take multiple drafts, or did you know right away?

AS: The “Cemetery of the New Blacks” is a poem whose words for the most part are not mine. It’s a 90% ready-made (found) poem based on an article I read in a newspaper that I always refer to via hyperlink. I don’t know the Cemetery that’s the theme of the poem, but I know the area and I especially know the feeling of having the history of my ancestors suffocated by hegemonic discourse and debased by the instruments of torture. At least on the maternal side of my family, I am the great-grandson of an ex-slave. I wanted the poem to convey some of my sensation of discomfort, not just in the face of the horror of the legacy of slavery, but also and mainly because I often have the feeling that in the environments in which I was socialized, Brazilian racism is relativized and slavery has been overcome. Despite being 90% ready-made—a found poem—this poem was not done in one pass. I knew it should be composed in decasyllables, ten-syllable lines, in order to have a rhythm that would allow me to read it. This is a survival strategy.

O CEMITÉRIO dos Pretos Novos é um poema cujas palavras em sua absoluta maioria não são minhas. É um poema 90 % ready-made a partir de uma matéria que li num jornal que sempre indico via hiperlink. O Cemitério tema do poema eu não conheço, mas conheço a região e principalmente conheço a sensação de ter a história de meus antepassados sufocada pelo discurso hegemônico e aviltada pelos instrumentos de tortura. Pelo menos da parte de minha família materna, sou bisneto de ex-escrava. Queria que o poema passasse um pouco da minha sensação de desconforto, não só diante do horror do legado da escravidão, como também e principalmente pelo fato muitas vezes eu ter a sensação que em meus ambientes de socialização o racismo brasileiro é relativizado e a escravidão foi superada. Apesar de ser 90% ready-made, este poema não foi feito de primeira. Sabia que ele deveria ser composto em decassílabos para ter um ritmo que me possibilitasse ler. É uma estratégia de sobrevivência.

EC: Something that is so striking about this poem is its bluntness, how it refuses to soften or look away. All these specific details, numbers, and names one after the other in the hands of a lesser poet might feel cold or even run the risk of getting bogged down, but here they create a compelling rhythm that subtly moves the poem with graceful flow. How did you find the balance between naming the atrocities for what they are while still cultivating dignity for the victims of these crimes?

AS: Thank you for your generous words, but perhaps in a different sense than you do, I consider myself a minor poet. Manuel Bandeira considered himself that way, and he is one of our greatest poets. I couldn’t be greater than Bandeira. I think I ended the previous answer by answering that question. My obsession with forms, not just fixed forms, but by means of forms, almost always starting with a form in order to write is a survival strategy, in the case of subject matter that for me is painful. This poem is published in the book trans formas são (trans forms action), from 2018, and to this day it is a difficult poem to read, especially when it mentions the broken bones of children. The obsession with forms is accompanied by an ear attentive to the melody and harmony of the poem. The option to write out the numbers in full is a way to compensate for the anonymity to which our ancestors brought from Africa were subjected.

OBRIGADO PELAS palavras generosas, mas talvez em um sentido diferente do seu, eu me considero como um poeta menor. Manuel Bandeira assim se considerava e ele é um dos nossos maiores. Não posso ser maior que Bandeira. Acho que terminei a resposta anterior respondendo a essa pergunta. Minha obsessão pelas formas, não só as formas fixas, mas por formas, quase sempre partindo de uma forma para escrever é uma estratégia de sobrevivência, no caso de temas que para mim são dolorosos. Este poema está publicado no “trans formas são”, de 2018, e até hoje é um poema difícil de ler, especialmente quando menciona os ossos quebrados das crianças. A obsessão pelas formas é acompanhada por um ouvido muito atento à melodia e a harmonia do poema. A opção de escrever os números por extenso é um modo de compensar o anonimato a que nossos antepassados vindos de África foram submetidos.

EC: This poem ends with a question, a choice that I think is so brilliant for how it leaves the reader. What do you think is poetry’s role in social and transformative justice?

AS: The final question is that which is outside of the ready-made, found-poem material, and was the question I asked in Rio de Janeiro, where the Cemetery is located, which I have not personally visited. In 2015 I was at the Museu do MAR (Museum of Art of Rio de Janeiro) and saw the exhibit, Do Valongo à Favela: imaginário e periferia (Valongo to Favela: Imaginary and Periphery), which dealt in large part with the gentrification process of that part of the city which resulted in the discovery of the Pretos Novos Cemetery. Seeing the different works of art around the theme of black cultural resistance and then going to the terrace of the Museum to think about what I had seen, and coming across the view of the nearby Museum of Tomorrow, whose construction was not yet complete, triggered many concerns that were summarized in the poem and in its conclusion. I understand that poetry, art, doesn’t have to have any function other than to be free. The artist must, on the other hand, have the job of working on the issues that affect him and then sharing these issues. Some issues, some questions, take a long time to develop, and I’m more interested in the questions than the answers. Perhaps the role of poetry, of art, is to sharpen our ability to feel and ask questions.

A PERGUNTA final é o que está fora do ready-made e foi a pergunta que fiz no Rio de Janeiro, na região onde fica o Cemitério que não visitei pessoalmente. Em 2015 eu estive no Museu do Mar e vi a exposição “Da Favela ao Cais do Valongo” que tratava em boa parte do processo de gentrificação daquela parte da cidade que resultou na descoberta do Cemitério dos Pretos Novos. Ver as diferentes obras de arte em torno do tema da resistência cultural negra e ir para a varanda do Museu do Mar para pensar no que tinha visto e me deparar com a vista para o Museu do Amanhã que ainda não estava pronto deflagrou muitas inquietações que foram sintetizadas no poema e nesse arremate. Eu entendo que a poesia, a arte, não tem que ter uma função além de ser livre. O artista deve por sua vez ter o trabalho de trabalhar as questões que lhe afetam e compartilhá-las. Algumas questões levam muito tempo sendo elaboradas e me interessam mais as questões do que as respostas. Talvez o papel da poesia, da arte, seja burilar nossa capacidade de sentir e de fazer perguntas.

EC: “Cemetery of the New Blacks” deals with some very heavy subject matter and historical trauma that still affects people today. When dealing with topics as great and all-consuming as this, I wanted to know if you had any strategies for protecting yourself and your mental and emotional health when visiting these very dark places?

AS: Well, we already know that I haven’t personally visited this specific place, but I’ve visited others and I carry this history in my skin. I remember one time, visiting an old gold mine, when a Black friend and I were very shaken to see the extremely narrow passages to which only children had access in order to extract the ore. After this visit, a colleague, descendant of European refugees from World War II, compared the sufferings and said she did not understand the weight given to the experience of exploitation of Black people in Brazil. We’ve been poorly prepared, since forever, to deal with the many forms of this horror. To be Black in Brazil or in the United States is to be educated from a very young age, to know how to avoid being approached by the police and being treated as a suspect. To be gay in the country that kills the most LGBTQUIA people in the world, to be Black, to be forty-eight years old, is to be endowed of necessity with experiences as to how to deal with the strategies of silencing and oppression. In the book assim na terra como no selfie / on earth as it is in the selfie, there’s a poem, “tapetum lucidum” (the name of a layer of tissue in the eyes of owls and other nocturnal creatures that enables them to see well in the dark), which deals with this ability that some of us have had to develop in order to survive in the dark: “não esquecer que se eles trazem trevas / podemos nos mover na escuridão. / justo no breu é que melhor dançamos” (“don’t forget that if they bring darkness / we can move in the gloom. / it’s precisely in pitch dark that we dance better”).

BEM, JÁ sabemos que este lugar especificamente eu não visitei pessoalmente, mas visitei outros e carrego essa história na minha pele. Lembro uma vez em que, visitando uma antiga mina de ouro, em que eu e uma amiga negra estávamos muito abalados vendo as passagens muito estreitas às quais só crianças tinha acesso para extrair o minério e depois dessa visita, uma colega, descendente de europeus refugiados da 2a Guerra, comparava os sofrimentos e dizia não entender o peso que era dado à experiência da exploração dos negros no Brasil. Nós somos lamentavelmente preparados para lidar com o horror de muitas formas, desde sempre.Ser negro no Brasil ou nos Estados Unidos, é ser educado desde muito pequeno, a saber evitar a abordagem policial e o tratamento como suspeito. Ser homossexual no país que mais mata LGBTQUIA+ no mundo sendo negro, tendo 48 anos, é ser necessariamente dotado de experiencias de como lidar com as estratégias de silenciamento e opressão. Tem um poema do livro Assim na terra como no selfie, “tapetum lucidum”, que trata dessa capacidade que alguns e algumas de nós tivemos de desenvolver para sobreviver em lugares mais escuros: “não esquecer que se eles trazem trevas/ podemos nos mover na escuridão. / justo no breu é que melhor dançamos”

EC: Carolyne, what do you think is translation’s role in decolonizing literature (if at all)?

Carolyne Wright: An interesting question. I don’t usually think of literature as colonized; rather, I think of the literature of any language as its own actualized entity, with its own origins, history, and influences upon it from other literatures; and, in turn, its influence upon the literatures of yet other languages. Of course, the literatures of languages with greater political power and cultural influence seem to dominate—one example could be the translation of English-language prose (especially novels) and theatrical works into languages worldwide. Comparatively little poetry written in English, though—apart from the classics (Shakespeare, Milton, the Romantics, some prominent Modernists such as T.S. Eliot)—gets translated to other languages, at least that I am aware of. That is, little modern and contemporary poetry.

Notable exceptions I know of in the context of Brazil include Elizabeth Bishop (1911-1979) who lived in Brazil for fifteen years with one of the country’s most renowned and beloved urban architects and public figures (Lota de Macedo Soares). With this personal connection, and with much of her later poetry set in Brazil, Bishop gained a certain renown there, and much of her poetry is available in bilingual (English-Portuguese) editions from a few noted Brazilian translators. But is her work available in Spanish, French, German, Japanese, Mandarin or Cantonese—to name a few world languages—without the personal history that she had with Brazil and the Portuguese language? I don’t know.

One realm in which colonization is an active issue is the relationship between the major languages of the so-called New World—English, French, Portuguese and Spanish—all of these originally European languages of the colonial settlers, and the original Indigenous languages of the Americas. Each Indigenous language had its own culture, practical lore adapted to local conditions, oral literature in song and story cycles, and even recorded communications (quipu, an ancient Inca method of knotting colored string in different patterns, for recording information) carried by runners throughout the Inca kingdom; and of course the Mayan and Aztec codices, most destroyed by the Spanish invaders. Many of these First Nation languages and cultures have been rendered extinct in the onslaught of colonial settlement and deliberate destruction of Indigenous identity. But in the past few decades there has been a Native American resurgence, with the creation of dictionaries and recordings by native speakers (often very elderly), and programs to immerse young members of these communities in their heritage language and culture.

Examples I am personally aware of in what we now call the Cascadia/Salish Sea region include the Lushootseed and Lummi languages—the new Poet Laureate of the State of Washington, Rena Priest, is a member of the Lummi tribe who has been studying her heritage language, an opportunity that she did not have in childhood. I am sure that PRISM International editors and readers could name several examples among the First Nations of Western Canada—indeed, despite the nation-state boundary imposed between Canada and the United States, Washington State and British Columbia are part of the same Salish Sea bio-region, with closely related Indigenous cultures, so PRISM International as a journal feels close at hand!

Canada is a country with two major official (European-origin) languages, English and French; and the United States, despite reactionary forces trying to deny and repress this, has an unofficial second language, Spanish. In other examples to which I feel connected, from the time I spent in the south of Chile, the Mapuche people are reviving their cultural and religious practices, and their language, Mapudungun; in the Sierra/Andes Mountains of Bolivia and el Perú, the large linguistic groups, Aymara and Quechua, have continued as the first languages of many Indigenous people, as has Guaraní for many people of Paraguay and the southern states of Brazil. And Alex no doubt could name other examples of Indigenous languages and cultures within Brazil.

EC: I personally make it a goal to have at least one translation in every issue of PRISM, but even amongst my reading board I find reluctance to engage with translations. Mostly, I think it’s due to uncertainty on how to approach them. How can folks in publishing increase the visibility of translations (eg. Naming translators on the cover), and what is your advice to how a reader can best engage with them?

CW: I agree that publishers must name translators on the covers and title pages of books in translation, and give credit to both the original author and the translator within the pages of literary magazines, including in the Table of Contents. This is perhaps an easier task with poetry, since poetry is more easily presented in both the original language and the translation on facing pages. Prose—short fiction or nonfiction—is not usually printed in bilingual format in magazines, at least not in my experience, due to considerations of length. The principles of translators’ rights and responsibilities have been set out by the American Literary Translators’ Association (ALTA), an organization I have been a member of for a few decades. I have been part of many conversations about such issues at the annual ALTA conferences and in discussions at more local events as well, so I always notice when a work that I know is in translation appears without translator credit—for example in the poem-a-day features that many literary organizations and magazines now sponsor, sending these poems as daily emails and posting them on websites. If, for example, the poem is by Cervantes or Matsuo Basho, appearing in English with no translator mentioned, I know that someone has gotten careless!

But publishing work in translation is an important project for many literary magazines; and there are many independent publishers dedicated to work in translation, either as their sole focus or as an important aspect of their program. In North America—in the USA and I’m sure in Canada as well—there is quite an active project of translation into English, much of it by university-linked poets, writers, and academics who operate from personal and professional interest in a world-wide range of languages and writers. Much of their funding comes from their own institutions, or from small grants from non-profit arts and humanities organizations; but many translators work mainly on their own, in their free time from teaching or other jobs, out of their own interest in the language and its writers. There are some professional translators for whom this work is a career—who translate, under contract from the major publishers, the major international novelists, and the poets who have won the major international prizes. But they are a high-profile minority of translators, at least of work into English.

Translators are often the best advocates for the works and the authors they translate—they know and love this material, from the act of reading it so closely in order to render it into another language; and their enthusiasm for it helps to overcome reader reluctance to engage. Over and over again, I have found that to be the case. In October 2021 I was part of a bilingual reading, via Zoom, of work of one of the Chilean poets, Jorge Teillier, whom I have translated. (In fact, some of my translations of this poet’s work appeared in PRISM International a couple of decades ago! ☺)

Eleanor Berry, one poet who attended this bilingual reading hosted by the Salem (Oregon) Poetry Project, sent an email after the event to the three readers, the two Oregon-based native speakers of Spanish, Efraín Díaz-Horna and Nitza Hernández-López, and the translator to English—moi! Here is what Eleanor wrote:

This was the first of the bilingual readings that I’ve attended. I had thought that my lack of Spanish would exclude me from experiencing the poetry. What I discovered, through listening to you, Nitza and Efraín, was how richly a poem is conveyed when performed by a native speaker of its language. Though I understood only occasional words and phrases, the structure, texture, and emotional arc of the poems came across beautifully. Then, Carolyne, your renditions into English gave me Teillier’s particular images, let me hear his poems as poems in my own native language. Any poet would be honored to have her or his work carried over as the three of you carried over Teillier’s.

These are comments (reprinted with everyone’s permission) that I as a translator find most heartening, and they encourage me to persist in this work of carrying across the poetry of one language into poetry in my native language, English!

EC: From what I understand, the translation of this poem (and all of Alex’s work by extension) has been one of close collaboration and vibrant discussion. I’d love to know more about how both of you approach the process of translating, and how the two of you work together.

AS: Carolyne is very familiar with Brazilian Portuguese and Brazilian culture. We are friends and know each other’s work. It’s quite true that she has the advantage in her knowledge as the translator of my poetry; I know and read her poetry, but not as a translator. We met in a very particular context, at an artists’ residency where I am a member of the governing body, acting as a kind of advisor. On the day we met, at a public presentation of work by new residents, I read a Portuguese version of a poem by Carolyne, and this created a connection that deepened over time. In the translation process, I always follow her, and she always wants me to give my opinion, to talk about options. I tend to answer questions more than intervene in her choices. In addition to these connections I’ve mentioned, Carolyne is an excellent poet who has mastered formal matters, which facilitates (more for her than for me) the translation process. Obviously there are always specific cultural questions that may arise, which I eventually answer or even intervene to suggest possibilities. But I tend to see the poems translated by her as our poems, as co-authored work.

CAROLYNE CONHECE muito o português brasileiro e a cultura brasileira. Somos amigos e conhecemos nossos trabalhos. É bem verdade que ela está em vantagem quanto a conhecer minha poesia. Eu conheço e leio a sua poesia, mas não como tradutor. Nos conhecemos em um contexto muito particular, numa residência artística em que sou do corpo diretor, atuando como espécie de conselheiro. No dia em que nos conhecemos eu li publicamente uma versão em português de um poema seu e iso criou uma conexão que foi aprofundando. No processo de tradução, eu sempre acompanho, ela sempre quer que eu opine, converse. Eu tendo a mais responder perguntas do que intervir nas escolhas. Além das conexões citadas, Carolyne é uma excelente poeta que domina as questões formais, o que facilita (mais para ela do que para mim) o processo. Obviamente há sempre questões culturais, específicas que podem surgir e que eventualmente eu respondo ou mesmo intervenho. Mas tendo a ver os poemas traduzidos por ela como nossos poemas, como um trabalho em coautoria.

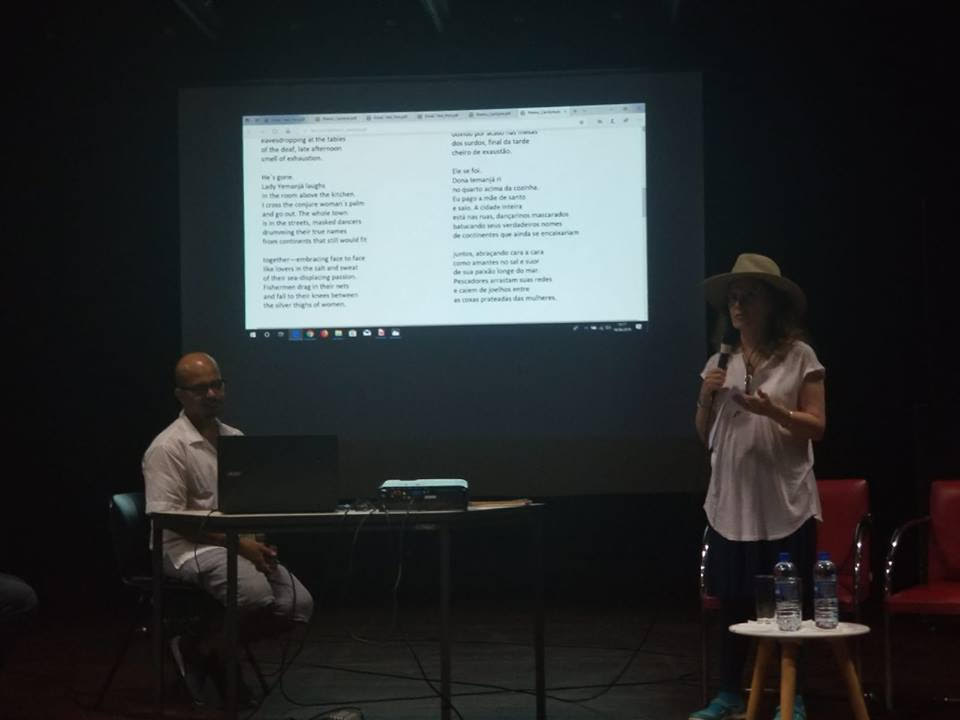

CW: In 2018, I spent eight weeks on the island of Itaparica, in the state of Bahia, at an artists’ residency at the Instituto Sacatar. During this residency, I met several artists from various genres, including Alex who, as a member of Sacatar’s Board of Directors, attended the Conversas com Sacatar, the first public presentation of work by the new cohort of Sacatar fellows, held at an institute in the city of Salvador. Two of my earlier poems, written about my first encounter with Bahia years earlier, had been translated to Portuguese for this occasion by Marcelo Thomaz, Sacatar’s Communications Director. I read the English originals, Marcelo read one and Alex read the other Portuguese translation, with the poems projected onto a screen behind us. I have one photo of this presentation! Alex visited Sacatar a few times during my residency, and I also saw him at a few poetic performances he gave in Salvador. Toward the end of my residency, Alex gave me a copy of his newly published book, trans formas são, which I read during the following months back home in Seattle. A few months later, I was reading this book on the bus going to and from Portuguese classes I was taking at the University of Washington. At some point, I messaged Alex to express admiration for his work, and shortly thereafter, he asked me if I could translate some of these poems for a bilingual chapbook. So that is how we started!

Our process has been quite collaborative: I prepare an initial version in English of each poem, then share it with Alex, along with questions I have about meanings of particular words or phrases, local slang or colloquialisms, allusions to places and historical events, etc., that most non-Brazilian readers would not be familiar with. Alex responds to my questions, and makes additional suggestions as needed. In fact, as a point of reference and for future writing about translation and about Alex’s work, I have saved the entire thread of Facebook Messenger correspondence between us as we worked on the poems of Alex’s that I have translated so far—it has been a quite enjoyable and nuanced conversation. It’s helpful that Alex reads and understands English quite well, so he follows what I am doing—of course, he jokes that his English is broken, and sometimes his Portuguese, too! We are both very verbal, and verbally playful—a character trait that I appreciate in many Bahians! Most of our correspondence, and conversation in Bahia or in the times we have spoken via Zoom or Skype, has been in Portuguese, which has been a huge benefit for my ability to hear, understand, and speak the language—with, I hope, a reasonably Bahian accent! ☺

EC: As a poem that documents how past atrocities are still relevant in the present, I’m curious about the challenges that “Cemetery of the New Blacks” presented in both its writing and its translation. Alex, I have no doubt that this is a sensitive, probably even divisive topic, in Brazil and I’m wondering how you crafted this unique voice that is at once matter-of-fact, empathetic, and unflinchingly pointed? Carolyne, were there images or moments in the poem that were emotionally hard to confront, or difficult to recontextualize for a new audience?

AS: I suspect that I have already answered this question, perhaps in a disappointing manner in the sense that the single speaker’s voice is an appropriation of discourse from a news report. But of course the selection, the point of view, and the strategy of shaping such a painful discourse into decasyllabic lines make all the difference. And when I repeat about the choice of decasyllables, it is not just because of the textual surface. It has to do with a diction I have developed over the years that is not just a form, but a structure for me to say the things I want to say.

EU DESCONFIO que já respondi essa pergunta, talvez decepcionando no sentido de que a voz única é uma apropriação de um discurso de uma reportagem. Mas naturalmente a seleção, o ponto de vista e estratégia de conformar um discurso doloroso em decassílabos faz toda a diferença. E quando repito sobre a escolha dos decassílabos, não é apenas pela superfície textual. Trata-se de uma dicção que desenvolvi ao longo desses anos e não se trata apenas de uma forma, mas de um suporte para eu dizer as coisas que quero dizer.

CW: The United States shares with Brazil a very similar, shameful history and legacy of slavery that continues to resound in contemporary life, in the relationship between African Americans here, and Afro-Brazilians in Brazil, and the so-called dominant white culture. I was always interested in social change in school, college, and then as a graduate student during turbulent times of the Civil Rights movement, the anti-War movements (Vietnam, and years later, Iraq and Afghanistan), and the movements opposing US support for military coups and dictatorships world-wide. I was in Chile for a year during the presidency of Salvador Allende (whose democratically elected government would be toppled the following year by those criminals Kissinger and Nixon in collusion with the Chilean oligarchs, on the first 9/11—the eleventh of September 1973), who would die during the coup along with thousands of his supporters over the seventeen years of military dictatorship. And I spent several weeks in Bahia during that same year, when Brazil—especially the Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous communities—suffered under a brutal military dictatorship, also supported over the course of several U.S. presidential administrations. So my heart and thoughts have long been with people everywhere, not just those struggling in the U.S., but all over the planet, particularly in the countries where I have spent time and where I have learned the language. My friendships and associations have been with people of many different backgrounds, ethnicities, cultures, and languages. So I was early on aware of, and fascinated by, all the differences between human groups, as well as the common humanity we all share.

Later, as a Writing Fellow at another residency—on Cape Cod, not an island but a peninsula!—I met and spent several years in a relationship with an African American poet and writer, and learned a lot from him about the risks and dangers of life as a Black person in racist America. In fact, my new book, Masquerade, is a memoir in poetry about those years, this experience! The more recent Black Lives Matter movement in the U.S. has made many of us much more aware of the ongoing challenges of being Black (or Native American, or Latino/a, or Asian) in this culture, and also of much of the concealed, denied, erased history of violence by whites toward Black people over the centuries. Swept under the rug, as Alex says in “cemetery of the New Blacks.” The gruesome violence of lynching throughout the South after Reconstruction and until the 1960s, the Tulsa Race Riots, the assassination of Dr. King, and so many other horrific stories are all too familiar to African Americans; and similar atrocities are known to Afro-Brazilians—all of these passed down in family lore, oral history, and more recently appearing in literature and historical texts for those who care and who pay attention to learn from them.

So the discovery of this mass grave of hundreds of Africans, unearthed near the waterfront of one neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, is a variation on a theme, Brazil’s own Holocaust. The first time I read this poem, I was fully engaged by the urgency of the subject and the vividness of the dramatic situation—it was an important poem! I found the impersonal, journalistic tone, the enumeration of corpses, the statistical details, the calmly reasoned explanation for breaking the bones of children, of burning the bodies and flinging them into narrow trenches to save space, quite chilling. But that was Alex’s intention, in taking these found texts from newspapers and archaeological reports and forming it all into this poem, in lines with a syllabic count, to give a structure to the text and also to prevent the poetic speaker’s emotions of horror and revulsion from breaking into chaotic cries from the heart. Those emotions must remain unstated but implied, rendered more powerful thereby, until the final question, which is the poet’s own. My job as a translator was to keep my own emotions out of the process, and to render the text as faithfully and empathetically as I could. I hope I have done so!

EC: Finally, what upcoming projects can readers look forward to?

AS: As I mentioned earlier, among my next projects I have a book already in press with poems about Bahia (mostly Salvador), minha terra tem ladeiras (my land has slopes), with illustrations specially done by editor Fernando Oberlaender, preface by Sandro Ornellas and blurb by Itamar Vieira Junior. In addition to working on the promotion of this book, I intend to deepen some research that I have done on the appropriation of texts and objects. I’ve been increasingly working with visual poetry and producing object-poems or “object-poeformances,” which consist of collages with letters and words cut out of packaging, magazines, and newspapers that I have consumed, collages which keep taking on three-dimensional shapes and recombining themselves into “readymades,” assemblages. This book, which ought to be called mottainai, is part of a series of actions that I have been contemplating about the destination of all that we consume. I have made use of metaphors of waste and reuse to produce discursive and visual poems. As soon as the pandemic cools down, I’m thinking of doing some exchange work at an artists’ residency in order to continue experimenting and exchanging. The project #experimentoscomletrasurbanas (#experimentswithurbanletters) needs to get out into the world a little, after nearly two years of social isolation. But first the pandemic has to end. For now, what I intend to do is to continue and live, therefore, creating.

COMO JÁ mencionei, entre os próximos projetos, tenho um livro já no prelo com poemas sobre a Bahia (majoritariamente Salvador), “Minha terra tem ladeiras” com ilustrações especialmente feitas pelo editor Fernando Oberlaender, prefácio de Sandro Ornellas e orelha de Itamar Vieira Junior. Além de trabalhar na divulgação desse livro, pretendo aprofundar algumas pesquisas que tenho feito sobre as apropriações de textos e de objeto. Tenho exercitado mais e mais a poesia visual e ando produzindo poemas-objetos ou poeformances-objetos que consistem em colagens com letras e palavras recortadas de embalagens, revistas e jornais que consumo e que vão ganhando formas tridimensionais e se recombinando em ready-mades. Esse livro que deve se chamar “mottainai” é parte de uma série de ações que tenho pensado sobre a destinação do que consumimos. Tenho partido das metáforas do desperdício e do reuso para produzir poemas discursivos e visuais. Assim que a pandemia arrefecer, penso em fazer algum trabalho de intercâmbio em uma residência artística para seguir experimentando e trocando. O projeto #experimentoscomletrasurbanas precisa sair um pouco pelo mundo, depois de quase 2 anos de isolamento social. Mas primeiro a pandemia precisa acabar. Por enquanto, o que pretendo é continuar e vivo, logo, criando.

CW: Right now I’m promoting my new book, Masquerade (Lost Horse Press, 2021), a memoir in poetry involving an interracial relationship of two artists and writers set against the backdrop of racist America. (Given the current racial and political climate in the U.S., this book may turn out to be controversial in some poetic circles, and regarded as courageous in others!)

Quietly, on the side, I am writing new poems for two future books: Mother of Pearl Women, a sort of poetic memoir from childhood up to the present, exploring the interweaving of personal and political history; and Solstice in the South, a sequence of poems started in Brazil, at the artists residency I held in 2018 at the Instituto Sacatar in Itaparica, Bahia (where I met Alex). This work was inspired by the cultural life and natural history of Brazil, especially the state of Bahia, the city of Salvador and the island of Itaparica, and it will be bilingual (English-Portuguese) so that speakers of both languages can enjoy it. (I have translated many of the poems myself already, with the assistance of certain Bahians!) And then there is another volume in progress of poems chronicling the misadventures of my alter-ego, Eulene: Broom-Closet Speakeasy: the Confessions of Eulene.

I am also working on more poems of Alex’s, and I have more volumes of translations of the work of Bengali women poets to assemble and publish—for all of these I will need to find publishers. And recently I was invited to put together a collection of my essays about poetry, poets, the writer’s life, and related matters, for the Poets on Poetry Series published by the University of Michigan Press. The title? Confessions of a Nonce Formalist.

Finally, since I was honored to receive a Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award for Brazil in early 2020, just a few weeks before the program was paused because of Covid-19, I will be returning to Bahia in the not-distant future. I will be affiliated with UFBA, the Universidade Federal da Bahia in Salvador, and so I will live in Salvador, where I will continue writing, translating more work of Alex’s from Portuguese, visiting schools and colleges to give talks and readings, and (hopefully) travelling a little bit. And of course, I hope to visit Sacatar again. The Commissāo Fulbright Brasil is most likely going to resume its program sometime in 2022, depending on conditions at the host institutions, and begin welcoming back Fulbright grant recipients after that time. As soon as I have more information, there will be a lot of plans for my husband and I to make in the next several months!