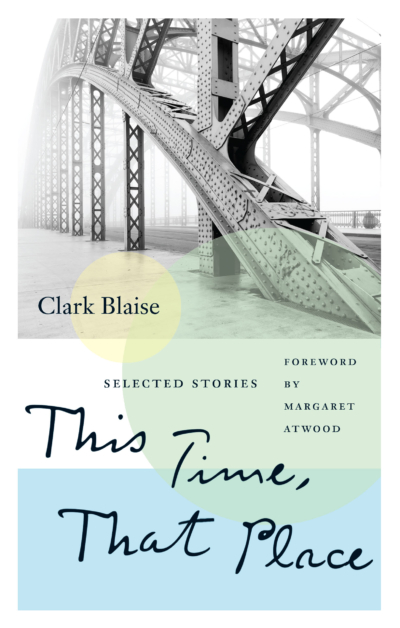

This Time, That Place

Clark Blaise

Biblioasis, 2022

Review by Brandon Fick

Who is Clark Blaise? Even some of the biggest literary aficionados may not be able to answer that question, yet This Time, That Place: Selected Stories goes a long way towards answering it. This collection of twenty-four stories covers Blaise’s almost sixty-year long career in work ranging from the backwater towns of 1940s Florida, the industrial cities of Ohio and Pennsylvania in the 1950s, cosmopolitan Montreal in the 1960s and 70s, and California’s Silicon Valley in the twenty-first century, stopping along the way in New England, Austria, Italy, and India. The consummate outsider, Blaise plunges into a variety of characters: the quirky, the marginalized, the only child, the immigrant, those caught between parents, borders, and languages. Truly, no other short story writer has chronicled North America like Blaise. As Margaret Atwood says in her foreword: “He’s the recording angel and the accuser, rolled into one. He’s the eye at the keyhole. He’s the ear at the door.”

Consider “A North American Education,” in which thirteen-year-old Frankie Thibidault literally tries to spy on a neighbouring woman through their shared bathroom wall. This story contains many of the hallmarks of Blaise’s craft. A striking opening sentence: “Eleven years after the death of Napoleon, in the presidency of Andrew Jackson, my grandfather, Boniface Thibidault, was born.” Imagistic yet unadorned writing: “It is 1946, our first morning in Florida… I had wanted to swim but had no trunks; my father took me down in my underwear. But in the picture my face is worried, my cupped hands are reaching down to cover myself, but I was late or the picture early – it seems instead that I am pointing to it, a fleshy little spot on my transparent pants.” It is a portrait of one of Blaise’s wayward, salesman fathers, and the young narrator’s coming-of-age. Here, the coming-of-age is sexual, revolving around the bathroom spying and a highly potent scene of sexual initiation at a county fair. Blaise is particularly adept at rendering the county fair’s strip show, its “smell of furtiveness, rural slaughter and unquenchable famine… The smell of sex on the hoof.” This scene is supremely memorable, if not disconcerting. And Frankie is a relatable, sex-obsessed teen who, in the end, witnesses something much more revealing than his neighbour bathing. If you read only one Blaise story, read “A North American Education,” an underappreciated twentieth-century classic that is on par with the likes of “The Lottery,” “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” and “The Swimmer.”

Of course, there are many impeccably crafted stories in this collection. “The Fabulous Eddie Brewster” follows the narrator’s Uncle Etienne, a displaced person in post-World War II France, who joins his brother’s family in Florida and reinvents himself as an American businessman. This story resonates through the decades despite being anchored in the 1940s, as it contains vital truths about America as a place and an idea, the inherent contradictions to the American Dream. “How I Became a Jew” depicts American racism from multiple angles within the confines of a Cincinnati elementary school. It also remains relevant, depicting a blunt clash of identities – Black, white, Jewish, Northerner, Southerner, communist, capitalist – where no one is free of bias. As usual, Blaise’s characters are uncensored and speak in an authentic vernacular. “Grids and Doglegs” depicts a singular Blaise protagonist, a sixteen-year-old whose hobbies include astronomy, archaeology, and chess, who could “spend whole evenings with a straight-edge, a pencil, and a few sheets of unlined construction paper” laying out “imaginary cities along twisting rivers or ragged coastlines.” On one hand, “Grids and Doglegs” is a familiar tale of an outsider with a crush on his friend’s sister, but Blaise eschews expected emotional beats and includes enough idiosyncratic details to craft an awkward, true-to-life story. In Blaise’s carefully rendered, evocative Montreal stories – “Extractions and Contractions,” “Eyes,” “I’m Dreaming of Rocket Richard,” “A Class of New Canadians,” “Words for the Winter” – the city is “mysterious” and “magical” despite its cold winters and subtle, ethnic divides. “A Class of New Canadians” in particular captures the duality of Montreal and perhaps all of Canada: officially a “superb” multicultural society, yet simultaneously a collection of disparate parts. The final, previously unpublished story, “The Kerouac Who Never Was,” packs incredible depth and emotion into ten pages, and is a fitting coda to Blaise’s body of work.

Both Margaret Atwood’s foreword and John Metcalf’s introduction are invaluable additions to the collection. Atwood places Blaise (and herself) amongst the burgeoning CanLit of the late 60s, and humanizes the chameleon-like man behind the stories. Metcalf discusses Blaise in relation to the Montreal Story Tellers of which they were both members, but also provides commentary on his craft: “Clark’s stories ran on wheels… The stories are so beautifully crafted and balanced in terms of their rhetoric that Clark seemed almost to disappear behind them.” Blaise can almost appear to have no distinct style, but he most definitely does. Similar to Alice Munro, he is understated on a sentence-to-sentence level, but the sentences accumulate, as does time and the characters’ complexity, until the reader realizes they have been reading the work of a serious and highly skilled practitioner of the form. Metcalf’s introduction also quotes Blaise himself, who calls the short story “an expansionist form, not a miniaturizing form… I think of the story as the largest, most expanded statement you can make about a particular incident. I think of the novel as the briefest thing you can say about a larger incident.” This poetic, sensual approach, often modulated by voice, is evident in a story like “At the Lake,” a portrait of Quebec lake life that makes up for its lack of plot with exacting detail and a startling climax.

The highly autobiographical nature of Blaise’s work has attracted some criticism, but as Metcalf puts it: “[The] stories are all different in emphasis and detail and each is a wonderfully crafted unique artifact. I suspect that for Blaise there really isn’t a clear dividing line between autobiography and fiction; he blurs the idea of genres.” As a young writer myself, these stories are examples of what you can do with the basic material of life. A story does not need fireworks or plot per se, but details, atmosphere, precise language, and most importantly, compelling characters. Later stories like “The Sociology of Love,” “In Her Prime,” and “Dear Abhi,” which depict Indian immigrants navigating both America and India, are no less impressive than earlier stories. In fact, some readers might consider these more technically proficient, as Blaise seamlessly inhabits voices that are not his own, finding common threads of humanity in an increasingly globalized, migratory world.

The publication of This Time, That Place is a cause for celebration. It is a half-century record of lives lived variously across the globe, of scheming French-Canadian fathers, artistic, long-suffering mothers, archetypal Southerners, Indian tech workers, multilingual only children. Not only does This Time, That Place prove Blaise to be a master of the craft, it also holds a mirror up to the reader. It may answer the question “Who is Clark Blaise?” but it raises the bigger, more important questions of “Who am I?” and “Where am I now?”

Brandon Fick is from Lanigan, Saskatchewan. He graduated from the University of Saskatchewan’s MFA in Writing program last year. During his MFA, he was mentored by Guy Vanderhaeghe. Brandon’s fiction has been published in The Society, in medias res, and Quagmire, and he’s published book reviews in Prairie Fire and River Volta Review of Books. His story, “Trip to Little Bighorn,” was one of twelve long-listed for the 2022 Bridge Prize. Brandon is currently the Fiction Editor for Quagmire and the Associate Prose Editor for spring.