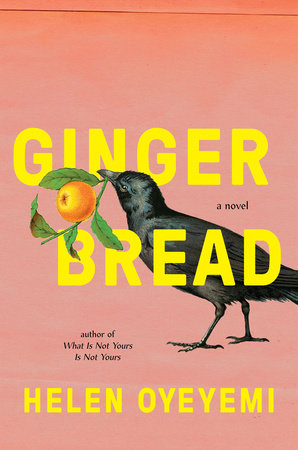

Gingerbread

Helen Oyeyemi

Penguin Random House, 2019

Review by Will Preston

There is a peculiar feeling, I believe, common to travellers in a foreign place. It arrives sometime after the initial jolt of finding yourself in a sea of unfamiliar tongues and faces, perhaps when you’re trying to cross the street or order a sandwich at a cafe, when you realize that not only the language, but the very logic of the place is different—the rules, as you know them, do not necessarily apply. To travel, then, is to not only relocate yourself physically but also mentally: to renegotiate your understanding of the world and your place within it. This is a dizzying and frustrating process, to be sure, but also a thrilling one, a reminder that the world is bigger and stranger and wilder than we often remember.

If you don’t have the time or the money or the inclination to travel, this sensation of wonder and disorientation can be found elsewhere: namely, in the books of Helen Oyeyemi. Oyeyemi is commonly described as a writer of “twisted fairy tales,” which is a little like calling Watership Down a book about rabbits: technically true—yet anyone who picks up Richard Adams’ classic novel expecting a charming tale about bunnies is in for a nasty shock. The same goes for Oyeyemi. It’s not wrong to say her books riff on fairy tales; her new novel, Gingerbread, features a character named Gretel, a far off and maybe-imaginary country, and a giant wooden shoe left over “from the days of giants.” (50) But she deploys these elements like a DJ sampling a well-known bass line or guitar lick, dropping references throughout like scattered breadcrumbs. Liberated from their original context, these classic tropes and characters become familiar in name only. In other words, Oyeyemi is less interested in retelling stories than in breaking them all the way down to the molecular level and reassembling them into something much weirder and irregular than what they were before.

Even for Oyeyemi, Gingerbread is a strange book. The novel revolves around Harriet Lee, her mother Margot, and her daughter Perdita, three generations of diminutive, gingerbread-baking, preternaturally grey-haired women. Harriet, we learn, grew up on a farm in a country called Druhástrana (which may or may not exist) before moving to the city to work as a “Gingerbread Girl” for the Kerchevals, a wealthy and deeply corrupt family enamored with Margot’s gingerbread recipe. The Kerchevals, in one of the book’s most indelible images, live in a house whose rooms constantly slide “up and down like beads on an abacus” between floors, causing the people who live there to constantly walk into the wrong room or step out onto a different floor. (137). This story, meanwhile, unfolds inside a complicated frame narrative in which Perdita falls into a coma in England many years later (after eating too much of Harriet’s gingerbread) and wakes claiming to have visited Druhástrana herself.

Attempting to track Gingerbread’s many left turns is a little like navigating the Kerchevals’ house of ever-shifting rooms: characters seem familiar until they decidedly aren’t, ostensibly well-trod storylines abruptly belch the reader into uncharted terrain. If you tried to draw a story map of Gingerbread’s plot, it would probably end up looking something like the Jeremy Bearimy gag from The Good Place. This, granted, is part of what makes Oyeyemi’s novels so reliably thrilling: it’s almost impossible to predict where you’ll be at the end of the paragraph, let alone the book itself. Her stories obey the nebulous logic of dreams: a winning lottery number spelled out on the backs of nine divers in a river; a boy who lives in a cupboard and convinces his entire family that he’s imaginary; a girl with two pupils in each eye, so that her eyes appear like “bottomless lakes.” (69) Did that really happen? we think, as if waking from a vivid and unsettling nightmare. What did it mean?

Even Oyeyemi’s sentences read like optical illusions, pockets of quicksand disguised as dry land. On each page, we’re greeted with some glistening turn of phrase—mouthy dolls, an unhaunted house, a country of “indeterminate geographic origin”—only to realize later that what we took to be a poetic flourish was an actual image. To call this magical realism would undersell Oyeyemi’s masterful manipulation of language, the way her prose hovers in the liminal zone between the metaphorical and the literal. If anything, Oyeyemi’s stories are anti-magical realist: instead of taking the fantastical and relating it in the prose of the everyday, her stories—the fantastical and everyday alike—unfold in the sprightly, fanciful language of fables.

Gingerbread is, to be clear, a dense, challenging read, filled with trap doors and winding, circular hallways. As Oyeyemi’s first novel since her unlikely 2014 bestseller Boy Snow Bird, it almost seems crafted as a rebuke against those who would reduce it to a mere “twisted fairy tale.” Like most of her previous books, it’s preoccupied with the relationships between mothers and daughters; with the secrets that hold families together and drive them apart. But it’s also a book about childhood, that distant country subject to its own inscrutable rules, where metaphor has yet to be discovered and the fantastical seems ever within reach. In Druhástrana, adults are referred to as “ex-children”—a reminder that adulthood is as much about what we lose as what we gain. We can never get that back. But with Oyeyemi, we can catch, however fleeting, a glimpse.

Will Preston‘s writing has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and has appeared in publications across North America, including The Common, The Millions, The Smart Set, Smithsonian Folkways, The Masters Review, and Maisonneuve. He holds an MFA from the University of British Columbia and lives in Portland, Oregon. Visit him at willprestonwriter.