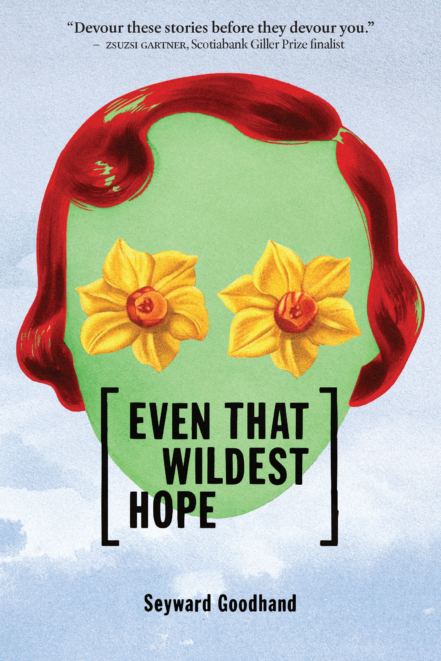

Even That Wildest Hope

by Seyward Goodhand

Invisible Publishing, 2019

Review by Kate Finegan

Seyward Goodhand’s debut collection of short fiction, Even That Wildest Hope (Invisible Publishing, 2019) begins with a question: “How can a man with love in his heart do the evil that I have done?” From this central question, ten stories unspool, traversing time and space and featuring characters that might be humans or monsters or both. These characters long for love, for excellence; they long for knowledge and clarity; they long to be less lonely. But longing in a broken world can prompt well-intentioned characters to eat woodland creatures alive, to slowly poison their fathers with arsenic, to cut a marigold pattern into a parachute before a resistance fighter jumps.

Longing manifests in the body as a physical ache, and the disquieting magic of these stories is the boldness with which they transfer that visceral pain to the reader. This is done through unflinching details. In “So I Can Win, the Galatrax Must Die,” two opening paragraphs of innocuous, charming description of the galatrax, a fictional “rare woodland creature,” serve as a sedative to distract from the grisly promise of the title. This section ends with the charming detail that “You may train a galatrax to take nuts from your hand” before noting that “galatrax has a gamy taste.” From this point, the story is pure ache. “The weightlifter does not want to think of herself as a person who devours two galatrae a day,” and yet, for three excruciating pages, the reader sits in discomfort with her as she devours “one of the pliant little balls of fur” piece by piece. The story is difficult to read; the galatrax is difficult to eat. After all, “She loves these fuzzy innocents. We all do.”

And yet. This collection dwells in the and yet, the large and small monstrosities that may be required of the living. There is an uncanny, unsettling sense of recognition. After the weightlifter has her gruesome meal, she goes outside and sees a mirror image of herself, a girl on a bicycle, wearing the same dress. In “The Fur Trader’s Daughter,” a girl sculpted from wax accompanies her father to the city, where he sells his taxidermy. When he gets sick at the market, she must get him medicine. The pharmacist says he can smell the flu on her. “Only when […] he saw the smooth absence of lines in my palm [..] did he look into my face” and asked “Are you for real?” Humans themselves cannot pinpoint imposters among their species, suggesting there is a fine line between the human and non-human.

In “What Bothers a Woman of the World,” the narrator introduces Agvagvat, a creature who follows her around, sliding across the floor “in the manner of a sea slug.” She wonders, “What right has a creature as exposed as Agvagvat to bear such hope?” After all, there is hope in these stories, alongside the cruelty. The intimacy of the point-of-view presents characters stripped bare of any pretense, of any privacy—there is nowhere to hide the worst of their natures—yet Goodhand treats them with compassion by exploring the fullness of their natures. She never hides their hope, the fact that they all want what they want, and how universal those wants are.

“Pastoral” and “Hansel and Gretel and Katie” use classic storylines to highlight the universality of these strange tales, to show that these characters are not so different from anyone we might bump into on the street or find in the pages of any more well-mannered book. The difference is that here, Goodhand casts an unflinching light upon the fullness of their ugly humanity, and the victory of this collection is that the characters’ messy, true humanity shines brightest here. After all, the wax girl does forgive her father, even as she waits for him to die. And after all, the witch in the final story only imagines pushing Hansel into the oven, which she would justify by feeding him a hot-cross bun just before putting him out of his misery, so that “At least his last feeling would be one of mouth-watering hopefulness.” Instead, she welcomes his sister when she comes at last. She watches them eat, and when starvation makes her desperate, she kills her beloved jersey cow, Esmerelda. She isn’t sweet to the children as they eat their meal of regrettable blood sausage, but she assures herself, “For better or worse, I kept us human.” This deeply unsettling collection stunningly, skillfully unveils the better and the worse of keeping human.

Kate Finegan‘s work has been published in Prism International, The Puritan, The Fiddlehead, SmokeLong Quarterly, Waxwing, and elsewhere. Her chapbook, The Size of Texas, is available from Penrose Press. She is Assistant Fiction Editor at Longleaf Review. She lives in Toronto. You can find her at katefinegan.ink and twitter.com/@kehfinegan.