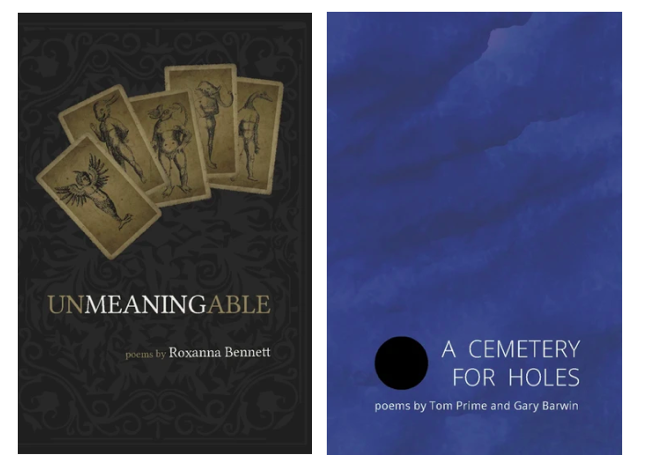

Unmeaningable

Roxanna Bennett

Gordon Hill Press, 2019

A Cemetery for Holes

Tom Prime and Gary Barwin

Gordon Hill Press, 2019

Reviews by Robert Colman

Starting a small press is a precarious, quixotic enterprise. It isn’t just the low (or zero) pay and long hours, but also the bigger question that floats above any such project: why? What does one hope to do that is somehow different? But I’m a cynic. Small press publishers and editors are enthusiastic craft hounds, sniffing out work that reveals an aesthetic and/or story that they wish to celebrate. And Jeremy Luke Hill (publisher) and Shane Neilson (editor) at Guelph, Ont.-based newcomer Gordon Hill Press have much to celebrate with the first two poetry collections they’ve published.

Unmeaningable, by Roxanna Bennett

On the Gordon Hill’s website it states that the press is looking for a diverse array of writers, but “particularly writers living with disability.” This makes perfect sense. Neilson is one of the founding members of the AbleHamilton Poetry Collective, the goal of which is to support poets with disability through poetry readings, panels, and a yearly festival.

It was at one of the AbleHamilton events where I was first introduced to the poetry of Roxanna Bennett, who gave a reading compelling enough that I sought out Unmeaningable. Bennett has described her new book as an exploration of her “lived experience as a mentally ill, non-neurotypical person who is also physically disabled.” The poetry is as direct as that statement. The book begins with the following:

Let me be a “poet of cripples” not

a patient etherized upon a table,

not a brain floating within a body.

In a moment I must be a body

in the place incision produces in a body,

previously intact. Inert, poor body,

inarticulate. Pain flees from the word “pain.”

Immediately Bennett is on the attack against the overly cerebral focus of The Modernists via a challenge to the often-quoted opening lines from “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T. S. Eliot, “Let us go then, you and I, / When the evening is spread out against the sky / Like a patient etherized upon a table.”

She goes on to say “Between meaning and the unmeaningable / is the trick of thinking I can fix what I can name.”

Bennett’s narrator recognizes that, as someone who identifies as both mentally ill and physically disabled, there is no possibility of this intellectualization of the self—body and mind are inextricably linked.

Later in the same poem Bennett asks: “Let me be any other word, any other body: / stone, swan, sycamore.” This trio of stone, swan and sycamore returns regularly throughout the book, representing aspects of self that can be interpreted variously, depending on context. At one point, “stone” suggests the weight of illness, as when the poet writes “’Patient feels like her skull/ is crushing her body.” The repetition of the words themselves seem to come as reminders of the individual as do the book’s many disparate parts.

Ultimately, the poems in Unmeaningable ask the reader to understand those who are disabled not as needing to be “solved” but rather respected as the people they are. This is the case in the poem “Best Wishes”, which read, in part:

…Cardinals

come when you call if you call with a palm full

of sunflower seeds but at least they don’t tell

you to get well soon at least they come when you call

The greatest conceit of Bennett’s book, however, is that it is a crown of broken sonnets. The sonnet is, to my mind, one of the ultimate forms in poetry, and in the context of Bennett’s work here, it can be seen as the ideal normative structure, as if someone is telling the poet “this is the box we ask you to fit into—please conform.” And for the first five pages, Bennett dutifully gives us square blocks of 14 lines each. But on page six, the structure bends and suddenly we have the two-page poem “Tree-Women, Delightful Forbidden Fruit”, which not only breaks form but is less connected to linear thought with the opening couplet: “Let us follow ghosts, the progress of a sick mind / towards the light ‘{(the tree is a dog)}’.”

Unmeaningable never gets to the point where the sonnet is abandoned outright but the poems that hold to the fourteen-line structure suddenly host visual gaps that suggest they’re breaking apart. These gaps suggest that the narrator, who is capable of stricture, needn’t be held to it, as in the “Unsustainable Blue Does Not Occur in Nature”:

A poet I was was I or just another cripple

crying violet not seen to flee the inaccessible

or need to see be seen comfortable Blue Rose

A Cemetery For Holes, by Tom Prime and Gary Barwin

If Bennett’s collection asks for readers to accept and revise their views of disability, A Cemetery For Holes serves as a poetic example of trauma in dialogue with the self and another.

The majority of this volume consists of a dialogue in poetry between Tom Prime and Gary Barwin. Prime’s primary focus is sexual trauma experienced in his childhood and as a hitchhiker at a time when he was homeless. As he says in his statement at the end of the book, he is interested in “alternative avenues to realistically live with trauma, knowing that the wound cannot be completely repaired, knowing that the power of writing is limited by imagination.” But Prime constantly demonstrates that imagination can be a powerful vehicle for viewing oneself and one’s lived experience from different perspectives. He starts the volume with the following lines:

I move to the Vancouver airport.

the plane is always one hour and forty-nine minutes late.

that hour and forty-nine minutes

becomes a room I build

out of billions of toothpicks.

Simple enough beginning but he let’s things get weirder quickly with:

every thousand years,

a little bird flies over my toothpick house,

carries a phone charger in its beak.

am I a bag of toffee? am I bark on a dead IV-tree?

the clouds evolve when they have occupations.

Like Bennett, Prime acknowledges his multiplicities, but rather than leaning on the natural world he links himself, here and elsewhere, to the detritus of the man-made world. Another example of this is in “We Have Done Nothing, but Forget We Breathe” when he writes:

why are the mountains

of my feet not spoken? they have

nothing but packs of airports

that growl at other worlds.

Barwin plays the role of sounding board for the majority of the book, reacting to Prime in his fabulist style. Because it’s Barwin, his responses are not coddling. Instead, I see them as playful encouragement, self-examination, and sometimes simply riffs on words that Prime plants in the preceding poem. To return for a moment to Prime’s opening “YVR,” Barwin’s response in “LGA” begins as follows:

I arrive at LaGuardia

one hour and forty-nine minutes after my death

my death is a room

filled with leaves

now it’s one hour and fifty minutes after my death

if the leaves are symbols

where’s the tree?

For me, A Cemetery For Holes is an important reminder of how communication should work—not always as a search for answers but as a respectful dialogue that builds on questions, many of which are random, and peripheral to what one might feel one “needs.”

This isn’t to say Barwin doesn’t express tenderness on occasion. One of the shortest poems in the book seems to be a moment when Barwin had to go back to the basic tenets of his teacher bpNichol to express a sadness and wish for succor. This is the “Poem” in full:

nightlack

grief lung

lake long

lungbird

lakefist

nipple

The book ends with six poems written in concert by the two poets. They sprawl on the page in a way that works well with the format of the book (an 8 x 9 inch square-ish shape) but won’t translate well here. But lines from the final poem (“Night Wrote Body: Limbilical”) offer an example of the expansiveness they allow their language:

pills are antlered pronouncements

of a classroom luscious in its gravel

Still later in the same poem, I feel a hearkening back to Bennett in:

swan burrows into its feathers sighs

“here in the ground it is owl listening to the ground dark.”

There is much listening in both Unmeaningable and A Cemetery for Holes. In Bennett’s work, there is a sense that she has listened too long to normative expectations, and by cracking the sonnet she is also cracking the pain of a shell that does not allow her pain its due. In the dialogue of Prime and Barwin we see an example of what Bennett hopes for—conversation untethered to expectation.

Robert Colman is the author of three full-length poetry collections, the most recent of which is Democratically Applied Machine (Palimpsest Press, 2020).