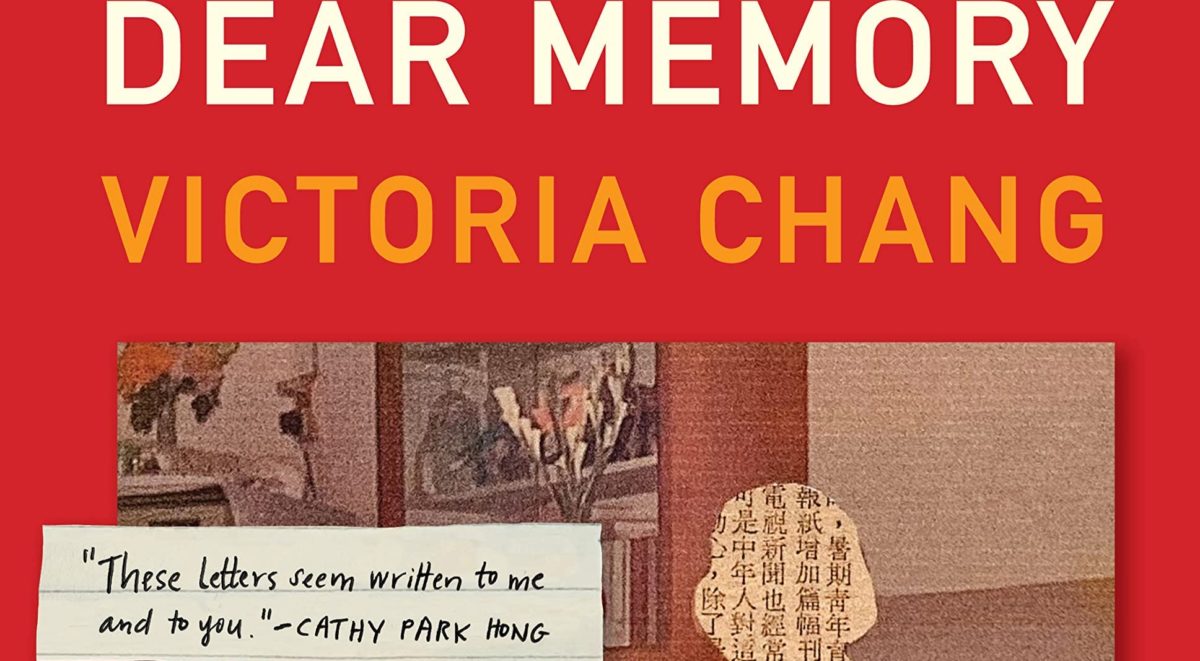

Dear Memory: Letters On Writing, Silence, And Grief

Victoria Chang

Milkweed Editions, 2021

Review by Cynthia Sharp

Victoria Chang’s multimedia poetic conversation Dear Memory: Letters On Writing, Silence, And Grief turns sorrow into art with transcendent understanding. Intergenerational suffering is expressed softly from silence that finds words, expands those words into larger truth, then weaves them together for resonance that expands beyond the holds of multi-layered oppressions that have weighed on the narrator through decades—as they weighed on her relatives before her. Chang approaches material—such as navigating ethnocentrism, misogyny, and racism—from a place of compassion for the immigrant mother who was scared to advocate at an American school, for a little girl without voice, and for an adult writer still searching through memory for the wisdom of her deep inner self to guide her own children.

Adding lines of poetry to photographs at the start of her chapters, Chang opens a conversation between interpretations of present and past, while the lyricism and repetition of the book’s longer prose poetry sections draw the reader in. Evocative rhythms and imagery transform life story into poetry with profound wonder: “I would like to know if you had some preserved salty plums, which we both love, in your pocket…if you had a book in your bag…to have known your father…if his voice was blue or red.”

As the letters progress, Chang’s use of juxtaposition opens space for discussion of the self. This is hinted at in an opening quote from Christian Wiman’s 2018 epistle to poetry, He Held Radical Light: “The sense of mortality—our own, but also that of those we most love—doesn’t only cast us backward. It also propels imagination forward.” Like Wiman’s verse, Chang’s sentence structure holds a profound space of emergence in thoughts such as: “Each breath was so beautiful, there couldn’t be anything but loss.” Beginning with centering grief in the pause between opposites, between “beautiful” and “loss,” a space is made for ancestors, even a wordless one—as well as for the narrator to grieve and for the self to rise. In this way, Chang places her dawning voice in the center of her sentences. Like Wiman’s bold use of a period between “backward” and the next clause ending in “forward,” Chang chooses to place a comma between her short clauses for a deliberate pause before the second concept. She punctuates to enhance juxtaposition, to guide readers to absorb the significance of the nouns and ideas placed a breath apart from each other—to infer the chasms of meaning between them.

Paradox permeates the narrator’s philosophical contemplation. In one of several “Dear Mother” chapters, Chang ponders, “I wonder if memory is different for immigrants, for people who leave so much behind. Memory isn’t something that blooms but something that bleeds internally, something to be stopped.” Even the alliteration of the repeated “bl,” and the consonance of the “s,” between the double vowels in the single-syllable, six-letter words “blooms” and “bleeds,” is constructed to accentuate the contrast between healthy blooming and painful bleeding—what memory means to untold trauma, chopped roots, and transplanted lives. Another chapter, one of several titled “Dear Daughter,” deliberates how to deliver the past without suffocating the strength of the future. “Do you know how astonished I was that so much had changed but so much hadn’t?” The narrator asks her biracial child. “Born in a more diverse and progressive state…half Asian, half white,” she implores her sleeping daughter not to let the tears wept over her body inform her view of herself or her ethnicity.

In this careful style, through her collection of letters to relatives and teachers from the past to the present, Chang builds a space beyond grief and burden, beyond mourning injustice, grounding the reader in the present—where they can shape, for themselves, a future of healing and empowerment. The proportionality and balance of Chang’s sentences allow paradox to carry the chronicle, to encompass ancestral memory from which fragments speak. Chang’s work steers silence into assertion, inspiring others to address their own folds of time by writing from their body—from their pain, joy, and the silence between. Dear Memory: Letters On Writing, Silence, And Grief is an internal dialogue laid out in letters that raises and addresses profound questions in exquisite, compelling language—the way poetry can hear and speak to silence.

Cynthia Sharp is a fine arts graduate student inspired by the rainforests and Pacific shoreline of her west coast home. She’s a full member of the League of Canadian Poets, as well as The Writers’ Union of Canada and was the City of Richmond’s 2019 Writer in Residence. Her work can be found in many literary journals including CV2, untethered and Toasted Cheese.